Today’s Odd Thought brought to you by hunger and a food-starved brain searching a mall on a Saturday afternoon.

Today’s Odd Thought brought to you by hunger and a food-starved brain searching a mall on a Saturday afternoon.

Today’s Odd Thought brought to you by hunger and a food-starved brain searching a mall on a Saturday afternoon.

Today’s Odd Thought brought to you by hunger and a food-starved brain searching a mall on a Saturday afternoon.

BUSK. A piece of whalebone or ivory, formerly worn by women, to stiffen the forepart of their stays: hence the toast, ‘both ends of the busk.’

BUSK. A piece of whalebone or ivory, formerly worn by women, to stiffen the forepart of their stays: hence the toast, ‘both ends of the busk.’

– 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue : A Dictionary of British Slang, University Wit, and Pickpocket Eloquence (unabridged) compiled originally by Captain Grose

When Dauviere came by Amalgam’s way,

When Dauviere came by Amalgam’s way,

he said he could not leave but could not stay:

forever he was trapped right where he stood,

and then he left the river town for good.

I wrote the Amalgam poems in the mid-1990s while nearly napping under a tree. They were seemingly nonsensical stanzas about a fictional town named Amalgam, its residents, and its larger world. I collected them one-by-one in a word processing file, which I printed and stashed away in a notebook.

In November 2009, I had a dream in which a hit man chased me and a group of “dream acquaintances” deep into the sub-cellar of an abandoned military building. In a room at the base of a rubble-filled shaft, he warned me to “dig up the Amalgam poems and post them.”

This poem completes my compliance with that instruction. I have posted one each Thursday, and now they are exhausted.

“Don’t feed him! If you feed a cat, it won’t catch mice.”

“Don’t feed him! If you feed a cat, it won’t catch mice.”

-Things a Hypothetical 19th Century Grandma Would Say

First link of the day comes from Jessica at BookEnds. Following up on a fantastic post by Nathan Bransford about the importance of keeping a “series bible” to keep track of the little details in your fictional world, Jessica explains the difference between a series bible and a style sheet, and why an author should seriously consider developing a style sheet before his or her work goes under the editor’s knife.

First link of the day comes from Jessica at BookEnds. Following up on a fantastic post by Nathan Bransford about the importance of keeping a “series bible” to keep track of the little details in your fictional world, Jessica explains the difference between a series bible and a style sheet, and why an author should seriously consider developing a style sheet before his or her work goes under the editor’s knife.

I am using that as my intro today because Jessica’s idea hadn’t even occurred to me, even though I do maintain a rough series bible for the Observer Tales. (The releasable stuff, I rework into Observer’s Gloss entries.) Now I have another project!

On to the rest of the links: Continue reading

From The Reshaping of Everyday Life : 1790-1840 (1988) by Jack Larkin:

From The Reshaping of Everyday Life : 1790-1840 (1988) by Jack Larkin:

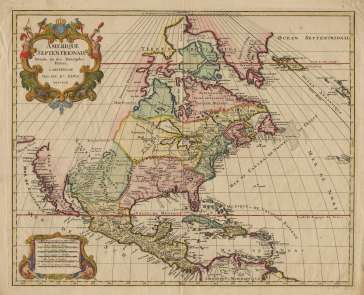

Just after Chloe Peck was married in Rochester, New York, in 1820, she wrote to her sister of “our family, which consists of 7 persons.” Living and eating together in the Pecks’ establishment were the newly wedded couple and five unrelated men and boys—the journeymen and apprentices of Everard Peck’s bookbinding shop.

Today “family” denotes people bound together by marriage and kinship … but early-nineteenth-century Americans almost invariably echoed Chloe Peck in describing their domestic groups as “families,” suggesting their sense of the household’s functional unity … [Everard] Peck a few years later wrote of his strong sense of responsibility for “the welfare of those connected with us, and the harmony and good order of our family.”

Afterthought: I whole-heartedly recommend this book to anyone who wants to understand the tenor and common details of early U.S. history.

Today is my last day at my day job for a while, so I’m decompressing in anticipation of a week off, otherwise known as my real job of loafing and writing.

Today is my last day at my day job for a while, so I’m decompressing in anticipation of a week off, otherwise known as my real job of loafing and writing.

(According to Mutiny on the Bounty co-author, James Norman Hall, “Loafing is the most productive part of a writer’s life.” I agree.)

So, instead of a bit of Advice From a Dude, or another short story, I think I’ll close out this Friday with a few “background” links: two from the dark days of the Revolution, one about a Carolina shipwreck, and two food-related links — complete with archaic recipes! Continue reading

igly. See ugsome.

igly. See ugsome.

ugsome. horrid, loathsome. Frequent almost to the 17th century; revived by Scott in THE ANTIQUARY (1816): Like an auld dog that trails its useless ugsome carcass into some bush or bracken. … Also ugglesome, uglisome (16th century) … A stronger form of ugly (which Chaucer in THE CLERK’S TALE, 1386, spells igly).

– Dictionary of Early English by Joseph T. Shipley (1955).