Blog Archives

Get this: A young human boy raised in the city by a family of lycanthropes finds himself hunted by a human-hating weretiger.

Get this: A young human boy raised in the city by a family of lycanthropes finds himself hunted by a human-hating weretiger.

What is it? A feature film, urban fantasy adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, using the anthology’s episodic structure in a Tarantino style, letting the setting have a strong presence alongside the main story of Mowgli, using side-tales like that of Rikki-Tikki-Tavi and Toomai.

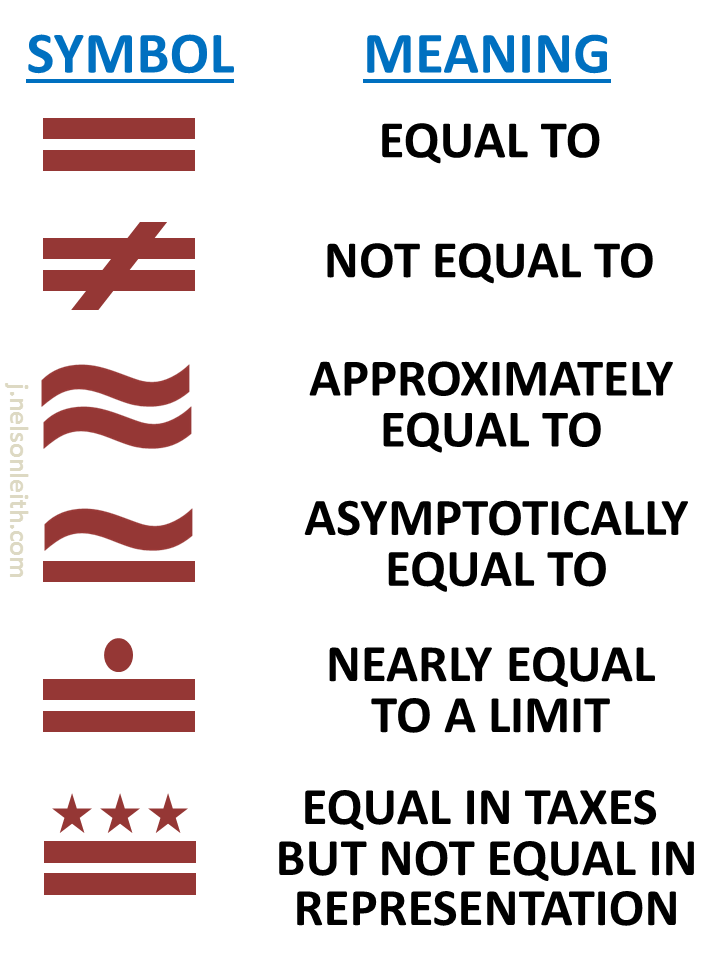

In honor of the DC Constitutional Convention, going on right now.

When I was in the Navy, I was in a rock band named Draft in Augusta, Georgia. That’s me on the left, playing lead guitar. Adam Pearson was the lead vocalist, Josh Johnson (out of frame on the right) was bassist, and Eric Booher was on drums.

When I was in the Navy, I was in a rock band named Draft in Augusta, Georgia. That’s me on the left, playing lead guitar. Adam Pearson was the lead vocalist, Josh Johnson (out of frame on the right) was bassist, and Eric Booher was on drums.

Eric and I had previously been a banjo-and-guitar folk duo called The Drunken Sailors in San Angelo, Texas. It was a fun romp.

Draft played primarily cover tunes, but we had a couple of originals. One of them I recorded after the band broke up, a rock tune about crime and rebellion called Garden.

I hope you enjoy it!

The Damsel-in-Distress is an intriguing trope, the female-gendered variation of the Salvand archetype, which is a character that needs saving. As the most prevalent expression of the Salvand, the Damsel not only informs our myth and literature, it embeds an insidious bias into our personalities, our culture, our politics. It’s a bias that corrupts our judgment, and thus our attempts at justice, like no other archetype.

The Damsel-in-Distress is an intriguing trope, the female-gendered variation of the Salvand archetype, which is a character that needs saving. As the most prevalent expression of the Salvand, the Damsel not only informs our myth and literature, it embeds an insidious bias into our personalities, our culture, our politics. It’s a bias that corrupts our judgment, and thus our attempts at justice, like no other archetype.

I’ve analyzed the Damsel before here, to show how it tricks us into perpetuating it by trying to save women from it. After all, the whole point of the Damsel is that “she” needs to be saved: trying to save women from the Damsel trope actually strengthens the Damsel trope. This ironic dynamic leads to a lot of head-desk moments, like when CBS’s Supergirl series failed the Bechdel Test‘s third bullet in a hook line intended to evoke girl power: “It’s not a bird, it’s not a plane, it’s not a man.”

Well, a few things have happened over the past couple of years that illustrate this principle neatly and deserve discussion, incidents involving a few of my genre favorites: fantasy (Game of Thrones), sci-fi (Fury Road), and hard-boiled fiction (In a Lonely Place).

Get this: A gender-swapped reboot of Gilligan’s Island.

Get this: A gender-swapped reboot of Gilligan’s Island.

What is it? A television comedy-drama based on the classic comedy of the same name.

Studying Islám at university, it struck me how saturated American popular culture is with imagery from various religions, Western, Eastern, Pagan, whatever. And, I don’t mean religious imagery used for its original sense, but used to illustrate some sentiment in everyday life. It shows the way these images get into our hearts and minds when we talk about feeling like we’re wandering in the desert, or turned away from the inn, or rolling the stone up the hill.

Studying Islám at university, it struck me how saturated American popular culture is with imagery from various religions, Western, Eastern, Pagan, whatever. And, I don’t mean religious imagery used for its original sense, but used to illustrate some sentiment in everyday life. It shows the way these images get into our hearts and minds when we talk about feeling like we’re wandering in the desert, or turned away from the inn, or rolling the stone up the hill.

But, I could not think of a single example of American popular culture that included imagery from Islám this way. Being a songwriter, I wondered what such an example might sound like, not a Muslim song but a song that employed some imagery from Islám to illustrate some sense of feeling lost or trapped like the Hebrews in the desert, or Mary and Joseph in Bethlehem, or Sysiphus in Hell.

At that time, I was fasting in solidarity with my Muslim classmates. In fact, several of us Christians were doing this after spending the first day of Ramadán gently teasing our Muslim friends by bringing colas and potato chips to class. If you’ve never done this, you should, even if you don’t personally know any Muslims. It’s a lot harder than Lent, let me tell you. A real learning experience.

And, from that experience came Forever Ramadán, a song of a fast that seemingly will never end. I don’t mean for this song to reduce the holy month practiced by the global Ummah to the existential suffering of an individual, but to show how imagery from Islám can stand alongside imagery from other religions in popular culture, deepening our understanding of how the great resonates in the small.