What qualifies someone to judge literature? Who gets to be one of the “gate-keepers” deciding what traditional publishers publish, a translator or reviewer of translations, or—the most sticky issue of all—a critic?

What qualifies someone to judge literature? Who gets to be one of the “gate-keepers” deciding what traditional publishers publish, a translator or reviewer of translations, or—the most sticky issue of all—a critic?

This all came to a head for me recently, after the season finale of the Breaking Bad prequel series Better Call Saul. Several critics complained that the final episode didn’t give us enough time get to know and care about Marco, a friend of James McGill (AKA Saul Goodman), before [SPOILER ALERT] he dies.

I consider television drama a species of literature, just as stage drama and film are. They all deserve the same respect, scrutiny, and expectations of excellence. This approach also helps to put criticism of a piece of literature into a larger context.

So, my first thought when hearing these critiques of the Marco episode was, “Not enough time compared to what?”

BETTER CALL A LARGER CONTEXT

Sure, a typical television season can run (if episodes are watched consecutively) for over eight hours, but a typical film can nail an emotional investment in under two hours. Considering the multiple plot-lines going on in most movies, under one hour of screen time. Marco, who also appeared in earlier episodes where he provided insight into Jimmy’s past and forewarned him about his brother Chuck’s sketchy personality, had plenty of time to get under our skins.

So, why did these critics not think so?

I call it “cognitive scale” and it has a huge impact on the quality of expert opinions. This scaling not only affects the ability to think “big picture” and “long term” (i.e., scaling in space+time) but also the so-called “broad view,” meaning the ability to locate and relate an idea to other ideas in a larger semantic context. Cognitive scale affects every field of learning, not just the arts.

Military theory provides a great framework in which to think about cognitive scale, as it explicitly distinguishes between tactical, operational, and strategic thinking. When reformers of military theory talk about a “tactical obsession” among strategic leadership, they are talking about cognitive scale. Strategy isn’t just tactics writ large, it’s a far more complicated thought process that arranges operational issues, which in turn arrange tactical issues.

And, strategic thinking is evolutionarily novel. For most of human evolution, we lived in very small (tactical) groups tackling very short-term tasks within a very narrowly circumscribed set of ideas. The strategic and, to a lesser extent, operational scales of organization simply haven’t been around long enough to impose selective pressure on the human mind. The natural result is that the typical human being isn’t geared to think at strategic scales.

Evolutionary science tells us to expect tactical obsession in the majority of human judgment. Operational thinking is exceptional, strategic thinking rare and precious.

When critics side-eyed Better Call Saul for not giving more time to Marco before he died, they were displaying tactical obsession, a limitation of their cognitive scale to the medium of the television drama.

ESCAPING THE “BOX”

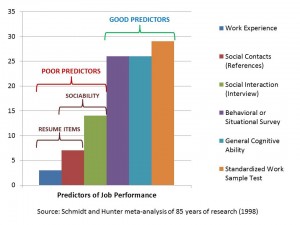

Too often, we rely on factors like experience, facility with jargon, and other tactical stand-ins for cognitive excellence when judging the qualifications of experts. Yet, we’ve known for some time now (see the graphic at right) that these sorts of qualifiers are poor predictors of performance. We ought to ditch them, but—for various reasons related to social instincts and cognitive limitations (paging Dunning-Kruger)—we just keep clinging to them.

Too often, we rely on factors like experience, facility with jargon, and other tactical stand-ins for cognitive excellence when judging the qualifications of experts. Yet, we’ve known for some time now (see the graphic at right) that these sorts of qualifiers are poor predictors of performance. We ought to ditch them, but—for various reasons related to social instincts and cognitive limitations (paging Dunning-Kruger)—we just keep clinging to them.

A smaller cognitive scale keeps critics from asking questions like: “Is this amount of exposure to a character really cramped when you look outside of television to other literary media?” A larger cognitive scale simply takes such contextual thinking as an expert’s due diligence.

Nevertheless, a critic suffering from cognitive scale limitations can still make a living as a critic because the people they are supposed to be guiding cannot detect those limitations. In fact, this is the great paradox of expertise: the clients of expertise have an innate difficulty in identifying those best qualified to provide them expert advice.

I intend to delve into this paradox more in future posts. Understanding it can not only help us promote better literary criticism, but it can help writers write better conflict in their stories, and can in fact help us build a better civilization.

Relatively larger scale thinking is often called “out of the box” thinking … by those inside the box. The proverbial “box” is typically taken to mean a philosophical box, limitations imposed by one’s set of ideas. I would assert that it is actually a cognitive box, the consequence of innate talent—like Michael Jordan’s talent at basketball or Alan Turing’s talent at mathematics—that some have and some do not.

It’s not about finding a better way of looking at things, but a better set of eyes altogether.