Narrative Role Playing is an attempt to elevate the unique essence of role-playing games (RPGs) above its board gaming and simulation gaming roots. To distill out the narrative core of RPGs. To bring role-playing closer to storytelling, closer to the emotional draw we find in novels, on the stage, and on the screen.

Narrative Role Playing is an attempt to elevate the unique essence of role-playing games (RPGs) above its board gaming and simulation gaming roots. To distill out the narrative core of RPGs. To bring role-playing closer to storytelling, closer to the emotional draw we find in novels, on the stage, and on the screen.

RPGs arose from the human instinct to tell stories, an instinct that goes back to the oral traditions of myth played out around Stone Age campfires. Although they certainly knew the role storytelling played in elevating RPGs above miniature wargaming, early RPG designers (even the sainted Gary Gygax himself) may not have fully understood the revolution they were kicking off. Storytelling wants its place in our lives, as the internet-driven deluge of self-published novels demonstrates.

RPGs are an attempt by that storytelling instinct to find its way into our play time. NRP is an organized effort to facilitate that instinct in players and game masters (called narrators), to bring RPGs more closely into alignment with an ancient, instinctive narrative tradition that we now see played out in television, theaters, and bookstores.

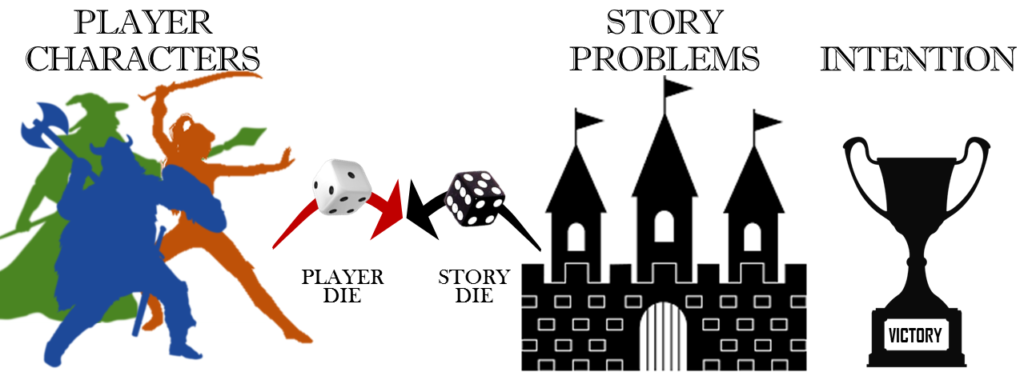

Simple Game Dynamic

The way NRP keeps the game dynamic simple is by resolving everything with a 2d6 roll, called simply a roll. The player character (PC)—or the PCs in concert—sets an intention, something they want to accomplish. This could be something as simple as getting through a doorway, defeating a foe, or crossing a stream. However, it could be as complex as piloting a ship, bypassing a computer system’s security, or convincing an enemy to turn traitor. Depending on gameplay, any of these could take multiple rolls.

The narrator determines what sort of story problem stands between the PCs and their intention, which can include the intentions of non-player characters (NPCs) and other aspects of the world’s environment. The players then decide what approach to use to overcome the story problem and reach the intention.

So, that’s the roll. One die represents the story problem and is called the story roll. The other die represents the PC approach and is called the approach roll. This sort of thing should be fairly familiar to veteran role-players, except that NRP has only one sort of roll. No separate skill rolls, attack rolls, saving throws, etc.

As Curly from City Slickers might say, “Just one roll.”

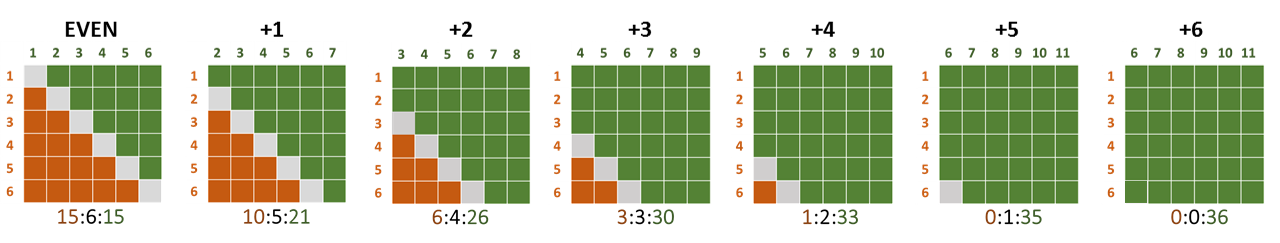

All modifiers in favor of (+) and against (-) PCs are added together. If the result is positive, this number is added to the approach die. If it’s negative, it’s added to the story die.

As you can imagine, it helps if these two dice are different colors so they don’t get mixed up as they bounce along the table.

The possible rolls are laid out in the table below, which is set up to focus on the die that has a bonus, whether it’s the approach or story die. Green indicates success, orange failure, and gray a tie. The meaning of these results differ based on the conflict the roll is resolving. To be fair, the meaning of these results should be laid about by the narrator before the dice are rolled.

As the table indicates, minimal changes in the bonuses and penalties result in huge differences in outcome. This instills game play with a narrative sense of serious consequence that the players should incorporate into their strategies. Once the consequences are known, the players have some serious decisions to make.

Note that an intention is anything a PC wants, including the implied desire not to be harmed or have their drives (explained later) contravened. Thus, rolls can be imposed on the PCs by the narrator, for example when the characters are attacked. In this case, the attack is the story roll and the defense is the approach role, based on how the characters are prepared against attack.

Narrative Dynamic

Here’s where it gets interesting. We’ve talked about the modifiers that influence rolls. But we haven’t gotten into where those modifiers come from or, more importantly, what effect success or failure has on PC development.

Here’s where it gets interesting. We’ve talked about the modifiers that influence rolls. But we haven’t gotten into where those modifiers come from or, more importantly, what effect success or failure has on PC development.

Success is important, but not to the point of power gaming. And success does not always mean reaching the player’s intention. Yeah, that’s a spin. In NRP, success is role-playing success. The players can lose their mission and still succeed so long as they stayed true to their characters. The story can be a tragedy, and the player characters (or PCs) can still advance. Just like in those novels, movies, and television dramas you love.

How is this accomplished? By adding a moral element to character development. Like in other RPGs, characters in NRP can improve their innate attributes and learned skills. They can become better at combat, at magic, at investigation, at coding, at stealth, at psy ops. But equal in importance, they also have drives, some of which are reward-oriented and some purpose-oriented, internal and external, which affect their rolls.

Attributes, skills, and drives are improved (or reduced) based on player decisions in gameplay, as judged by the narrator. But, only drives affect character advancement.

Unlike with attributes and skills, character can act in service to or against their drives. Acting against their drives (whether internal or external) penalizes the characters’ rolls. Acting in service to drives adds bonuses. But, for advancement from level to level, it matters whether these drives involve self-indulgence or self-sacrifice, creating a tension. The player can be faced with the risk of losing a particular roll by acting contrary to a drive in order to earn an experience boost in order to advance the character.

At early levels, sacrifice is called for, which means suppressing internal drives and expressing external drives. But, at a certain point, the character must be true to himself or herself in order to advance, which means expressing internal drives and suppressing external drives. Eventually, the character has to reconcile the selfish and the altruistic, the internal and external, to reach the highest levels.

And, in each roll, the player can decide whether to suppress or express their character’s drives. It puts the impetus for advancement on the player.

But, what ultimately matters for advancement is not winning encounters, but staying true to internal or external drives. In other words, role-playing. Serving the narrative facing the characters.

Advancement in NRP

Too many RPGs just plop PCs down into the world on their own at first level, very unlike both reality and the best stories. They are also typically burdened by steep advancement disparities that focus gameplay on wargaming min-maxing of skills and attributes rather than role-playing. No problem if that’s what you’re into, but for players who want more meaningful, narrative, mythic gameplay, something is missing.

NRP addresses this not only with drives, but by basing character advancement on those drives. Advancement in NRP aligns with the archetypes of myth and art, as well as real-world Medieval trade guild hierarchies, and is not only based on drives but on the influences of those drives’ on gameplay as the character moves from level to level. Significantly, NRP advancement is completely independent from improvement in attributes and skills.

NRP advancement moves through four moral stages and archetypes.

BEGINNER (levels 1-3) This stage aligns with the apprentice level of guild development and the companion archetype of myth and fiction. Think Samwise Gamgee in Tolkien’s Middle Earth epic or Elizabeth Swann in the original Pirates trilogy. The Beginner, an apprentice or companion type, is striving to the status of a Competent, a journeyman or hero type, and this is the key to character advancement.

During this stage, the character looks to role models, or a specific character as a role model, in order to learn how to be a better whatever he or she is destined to be. This can be a beginning warrior, rogue, technician, pilot, wizard, hacker, diplomat, whatever.

The character can be a sort of henchman (in traditional RPG terms) to another character, can seek purpose by following a legendary example, or can adhere to the teachings of sages/experts he or she has read. The main point is that the character is not yet an independent agent, still “learning the trade,” and not quite ready for prime time.

In the Beginner stage, the character’s immature naïveté and youthful zeal make them less susceptible to selfish internal drives. This may seem counter-intuitive, since youths are typically self-indulgent, but adventurers are a different archetypal sort. They are first to enlist in just wars, first to stand against oppression and tyranny, first to devote themselves to causes larger than themselves.

This means that negative modifiers from internal drives are completely eliminated for characters in the Beginner stage, unless the player chooses otherwise. Likewise, bonuses from external drives can be doubled, at the player’s discretion. This is the Beginner’s Luck we’ve heard so much about. Also, when a character is in the company of a Competent character (levels 4-6) they can enjoy an inspiration bonus of +1 to all rolls.

To rise from level to level as a Beginner, and to advance to the Competent stage, external drives must have reached a certain high level based on experience. Improvement (or reduction) of drives, just as with attributes and skills, is based on the narrator’s judgment of player decisions. When the player wins a roll by expressing a drive, the narrator can choose to count that toward improving the drive, i.e., improving its modifier.

COMPETENT (level 4-6) This stage aligns with the journeyman level of guild development and the hero archetype in myth and fiction. This is familiar as most main characters of myth and fiction are heroes. The Competent has proven himself or herself and is moving forward in maturity.

COMPETENT (level 4-6) This stage aligns with the journeyman level of guild development and the hero archetype in myth and fiction. This is familiar as most main characters of myth and fiction are heroes. The Competent has proven himself or herself and is moving forward in maturity.

During this stage, the character is struggling with the purpose instilled by external drives and with the sacrifice of suppressing internal drives. Competents are trying to make sense of who they are in the context of their external quest or quests. Characters at the other stages vie for the Competent’s attention, encouraging either internal or external drives.

In the Competent stage, the character is somewhat possessed by external drives, and torn by all drives, making life very difficult for characters at this stage. (For this reason, it’s a good idea for a Competent character to be part of a team.) The gameplay effect of this is that all drives can be doubled as penalties, if the player chooses, but also that the player can elect to disregard selfish internal drives only when they offer bonuses. This decision to disregard internal drive bonuses should be rewarded by the narrator with improvement in skills and attributes involved in the roll.

Likewise, the narrator should watch for opportunities to reduce the Competent’s external drives, indicating a growing cynicism toward self-sacrificing purpose. The reason is that, in order to rise in levels as a Competent, the character’s external drives must have a certain low level, moving in an opposite direction from the Beginner’s journey. The hero has grown weary of sacrificing in service to external drives.

CYNIC (level 7-9) This stage aligns with the freeman level of guild development and the rough archetype in myth and fiction. Think Han Solo, Jack Sparrow, or Aragorn. The Cynic character has somewhat abandoned devotion to higher purpose and is either seeking personal gain or just going through the motions of adventuring.

CYNIC (level 7-9) This stage aligns with the freeman level of guild development and the rough archetype in myth and fiction. Think Han Solo, Jack Sparrow, or Aragorn. The Cynic character has somewhat abandoned devotion to higher purpose and is either seeking personal gain or just going through the motions of adventuring.

During this stage, the character is suspicious of whatever sense of destiny or higher aspiration might have once driven him or her. The Cynic scoffs at the zeal of the Beginner, the struggle of the Competent, and the noble presentation of the Expert. The Cynic is the most likely to betray his or her team-mates for personal gain or out of skepticism, which can play into character advancement.

In the Cynic stage, bonuses and penalties from internal drives can be doubled, at the player’s discretion, while penalties and bonuses from external drives can be halved, rounded down. Likewise, when not in company with a Competent character, the Cynic suffers an apathy penalty of -1 to all rolls. To create tension between winning specific rolls and character advancement, the narrator should reward the Cynic’s following external drives and defying internal drives with improvement to drives, attributes, and skills.

In order to rise in levels as a Cynic, the character’s internal drives must have a certain low level. The Cynic rediscovers his devotion to external purpose.

EXPERT (level 10-12) This stage aligns with the master level of guild development and the guru archetype in myth and fiction. This is the Gandalf or the Kenobi of the party. The Expert character has integrated internal and external drives into a sort of balance.

EXPERT (level 10-12) This stage aligns with the master level of guild development and the guru archetype in myth and fiction. This is the Gandalf or the Kenobi of the party. The Expert character has integrated internal and external drives into a sort of balance.

During this stage, the character uses their improved skills and attributes to overcome conflicts between their internal and external drives. They are subtle contrarians, tempering the zeal of Beginners, encouraging the struggling Competent, and scolding the scoffing Cynic.

In the Expert stage, external bonuses and internal penalties can be doubled at the player’s discretion, external penalties and internal bonuses halved. Narrators should strongly reward serving external drives with improvement in skills and attributes.

At some point during level 12, a player with an Expert character should seek an opportunity to retire the character. If the player is hesitant, the narrator should nudge in this direction. The narrative tension for characters at this level is thus the knowledge that the character’s play is soon to end, and the current quest takes on greater significance.

Types of attributes, skills, and drives

Types of attributes, skills, and drives

There are no classes in NRP, but the various characteristics of characters are organized to lend themselves to traditional RPG and narrative archetypes. This is expressed in four types: Vital, Physical, Social, and Mental. A fifth type of skill, Crafting, draws on the primary four types in order to create objects.

These types help define and categorize the various attributes, skills, and drives, and thus they influence rolls. There are also three sorts of rolls derived from these types. Execution rolls are the most basic sort, representing taking direct action with the relevant attributes, skills, and drives. Preparation rolls are intended to set up and influence later execution rolls; this can include stealth, maneuvering, and communicating future actions. Training rolls are intended to help improve attributes, skills, and drives.

Now, let’s delve into the types of attributes, skills, and drives.

Vital. The essence of vital characteristics is transforming or expressing oneself. When they are paired with physical, social, and mental characteristics, vital actions involve transforming or expressing one’s individual will outward to affect the environment. All of the supernatural aspects of the game setting—magic, psychic abilities, super powers—are managed through vital characteristics.

Vital. The essence of vital characteristics is transforming or expressing oneself. When they are paired with physical, social, and mental characteristics, vital actions involve transforming or expressing one’s individual will outward to affect the environment. All of the supernatural aspects of the game setting—magic, psychic abilities, super powers—are managed through vital characteristics.

Vital training, called contemplation, can be purely individual meditation, prayer, or recitation, but it can also involve group chanting, prayer circles, and similar interactive practice. Vital execution, called transformation, includes all attempts to adjust, invoke, or resist a character’s drives, as well as attempts to use a character’s vital attributes to effect physical, social, and mental outcomes.

Physical. The essence of physical execution, called exertion, is transforming the character’s physical environment, including other characters and objects. Physical training, called exercise, can involve individual training or sparring with a partner. When sparring against a partner, physical training follows the rules of exertion toward the improvement goals of exercise; the character conducts fake exertion with a partner in order to improve physical characteristics.

Physical. The essence of physical execution, called exertion, is transforming the character’s physical environment, including other characters and objects. Physical training, called exercise, can involve individual training or sparring with a partner. When sparring against a partner, physical training follows the rules of exertion toward the improvement goals of exercise; the character conducts fake exertion with a partner in order to improve physical characteristics.

In combat, physical exertion means attempting to damage another character, or (a preparation action) maneuvering that character into a disadvantageous position. If the point of maneuvering the opponent into disadvantage is to communicate the character’s martial superiority, rather than improving subsequent execution rolls, this means the preparation roll is to communicate that superiority.

Note that combat actions can be modified by vital attributes (for example, using one’s POWER to increase one’s GRIP, if applicable), but also by social attributes (like sensing the opponent’s morale) or mental attributes (like recognizing the opponent’s fighting style). These modifications require a preparation roll that then modifies the execution roll.

It should also be noted that combat-like physical actions against objects are treated like combat actions. For example, attempting to hit a lever with an arrow in order to toggle it, or kicking a door to open it, or trying to smash a magical ring with an axe.

In movement, physical action means attempting to overcome opposition in the physical environment: climbing a wall, balancing in a precarious place, or swimming. The physical opposition might even be the character’s own limitations, as when the character attempts to struggle longer than his or her ENDURANCE would allow.

Like combat actions, movement actions can be affected by vital powers and mental knowledge.

Social. The essence of social characteristics is transforming the character’s social environment by negotiating relationships, uncovering the drives of others, and manipulating those drives.

Social. The essence of social characteristics is transforming the character’s social environment by negotiating relationships, uncovering the drives of others, and manipulating those drives.

Social execution, called negotiation, involves acting directly against the personalities of other characters. This can include aggressive attempts at manipulation and helpful attempts at encouraging or otherwise improving other characters. Social training, called rehearsal, can be purely individual acts of practicing social characteristics, but can also involve interacting with a willing audience, social sparring, which would follow the rules of negotiation toward the improvement ends of rehearsal.

Note that, like physical actions, social actions can be affected by vital, physical, and mental attributes.

Sometimes, the target characters are amenable to the social transformation, in which case all modifiers make the PC’s attempt more likely. Sometimes, the other characters are defensive against the PC’s goal, which results in a typical roll in which the opposition modifier is subtracted from the approach modifier.

Many cases of negotiation are more complex. For example, if an NPC secretly wants to help the PC’s intention, but is suspicious of his or her motives, or fearful of the consequences. In these cases, multiple rolls might be required, the early ones to overcome the NPC’s reluctance—in which a normal antagonistic subtraction of modifiers applies—then later to seal the deal, if (and only if) the earlier rolls were successful, in which the modifiers are combined positively. This process is helped along if the character is subtle enough to begin by trying to uncover the target’s motives and concerns before attempting to negotiate the new relationship.

Some social actions are more broad, targeting an entire group of people. The character might be trying to boost a group’s morale with a song or inspiring speech, calm a rowdy crowd with an impromptu warning, or sow suspicion with a well-placed innuendo.

As with physical exertion, social negotiation can also have a stealth component. When the character is trying to disguise his or her true goals during a social interaction, a stealth preparation roll should be made first to see how well the character has assessed the situation. The result of this roll modifies subsequent social execution rolls.

Mental. The essence of mental characteristics is transforming the character’s understanding of the environment.

Mental. The essence of mental characteristics is transforming the character’s understanding of the environment.

Mental execution, called investigation, involves acting directly against the gaps in one’s understanding of the world. This can include individual attempts to sense things or figure things out, rational debate with others, and (paired with negotiation) attempts to elicit information from others.

Mental training, called study, involves practice to improve one’s mental attributes and skills. This can be purely individual reading or going over mental notes, but can also involve recruiting others to test one’s knowledge and reasoning, which would follow the rules of investigation toward the ends of study. Note that “studying” information previously unknown to the character would, in NRP terms, follow the rules of investigation, not study.

Also note that, like other actions, mental actions can be affected by vital, physical, and social attributes.

Crafting. These actions are similar to combat actions in that the character is attempting to create an effect on an other, in the case of crafting some raw substance intended to become a useful tool.

Crafting. These actions are similar to combat actions in that the character is attempting to create an effect on an other, in the case of crafting some raw substance intended to become a useful tool.

However, unlike purely physical actions, crafting is necessarily affected by social and mental characteristics. The character’s mental knowledge obviously affects crafting, but social characteristics can also affect how the resulting tools are received. For example a crafter with high mental characteristics but low social characteristics can craft objects that are practically effective but ugly, repulsive, or unconvincing. On the other hand, a crafter with low mental characteristics but high social characteristics can craft objects that are convincing but impractical. Its flaws would be apparent to those with appropriate mental characteristics, but others might be taken in by the elegance of the creation.

Some case studies to make things clearer? Okay.

Singing an existing ballad to move an audience is simply a social action, a negotiation. Composing an original ballad is a crafting action, and would invoke the character’s mental and social characteristics. If the crafter’s mental characteristics are too low, the narrator could rule that the logical flaws in the lyrics might strike listeners with high mental characteristics as jarring. Listeners with lower mental characteristics, however, might be quite moved.

Or, let’s say a character is trying to invent a more effective way to hack into an enemy’s cyber-network. If the crafter has high mental characteristics but low social characteristics, the resulting tactic might be highly effective, but seem clumsy or irrelevant to characters with low mental characteristics. Characters with high mental characteristics, however, might see the logic in the approach.

Like other actions, crafting can involve both execution and training styles. Execution crafting, called creation, involves the crafting of new tools. Training crafting, called methodology, involves crafting new ways to create tools. This is a subtle distinction, and the details must be worked out between the players and narrator.

For example, a player may want the character to craft a better way to forge weapons, or a more efficient way to separate bad ingredients from chaff. In general, methodology should be far more difficult than creation. The narrator has an ultimate veto over methodology, as it could drastically alter the game setting.

Crafting can also involve multiple steps, for example binding cordage from raw fibers and then weaving that cordage into a basket. Or, mining raw ore, smelting it to purity, then smithing it into a useful tool. Or, selecting proper ingredients, preparing them, then mixing them into an effective medicine. Each of these steps should require a separate action roll. Sometimes, the character is only involved in one of these steps, for example a character purifying gold that some other character will then use to create jewelry or coins.

How narrative play works

The gameplay of NRP follows the pattern of story-telling, drawing insight from myth, novels, and film, as well as military theory. There are several nested layers of gameplay, representing the immediate tactical situation of the PCs, the larger operational situation, and the over-arching strategic situation. Each of these layers have their own goals, implying different player intentions, different opposition, and thus different approaches.

Situations PCs find themselves confronted with in NRP are nested in a neat, narrative hierarchy of time periods: actions, scenes, acts, episodes, and franchises.

ACTION. An action is, as the name implies, a single action taken by the character(s) in response to the current, tactical situation. This can involve a single action roll, or multiple action rolls addressing different aspects of the action. For example if the character is trying to sneakily convince someone, this would require a preparation roll for stealth, the result of which then modifies the social execution roll. Or, if the character is attempting a riposte, this would require a defensive combat roll (a preparation roll), the result of which would affect the following offensive combat roll (an execution roll).

Actions have no set length, but they are generally short.

Some examples of action types? A combat action comprises a quick series of physical maneuvers, attacks, and defenses. Other physical actions include chases, stealth maneuvers, and difficult motions like diving, climbing, and leaping across gaps. A social action comprises a series of comments, gestures, and other communications, things seeking to seduce, encourage, or manipulate. A mental action comprises a series of investigations, calculations, and other attempts to work through a set of information, things like scientific inquiry, engineering, and tactical analysis.

The defining factor of an action is that the characters face an immediate situation, their intention and the interfering opposition, and elects how to deal with it, the approach.

SCENE. A scene is the culmination of multiple actions. The end of a scene is the climax of a series of actions that have a common, over-arching situation.

The scene is the basic unit of time in NRP. When designing the game, the narrator should define each scene according to a diverse typology of scenes (combat, chase, negotiation, investigation, etc.) described in the Narrating a Game chapter. We’re all familiar with these types of scenes from novels, films, and television shows.

The narrator may, if he or she has a well-defined situation for a scene (meaning it has a well-defined assumed intention and a well-defined opposition in relation to character drives) call for an scene roll at the beginning of the scene, presenting the players with foreshadowing to allow them to make an informed choice of approach. How to manage this is described in Narrating a Game. The result of this scene roll modifies the action rolls, based on how those actions adhere to the overall approach the players chose.

If the players initially expect their characters to fight, but in the course of the scene they negotiate instead, the result of their scene roll is a penalty because they had prepared (vitally, mentally, emotionally, and perhaps physically) for a different situation. Likewise, if they choose for their characters to hold out for information (an investigation approach), but end up fighting, the result of their scene roll is a penalty. But, if they follow through with their original scene approach, the result of the scene roll is treated as a bonus to action rolls during the scene.

Sometimes the outcome of the actions in a scene fit the story (meaning the scene type) the narrator has laid down. Sometimes, however, the characters’ actions will lead to a scene type that the narrator had not expected. This is one reason NRP provides the narrator with a typology of scenes, to help him or her shift gears when the players go off-script.

For example, if the narrator wrote the scene as combat and the players elect to flee, the scene can become a chase. Likewise, if the scene is written as a debate and a character looses his or her cool, it can become a fight.

This is a tricky part of the narrator’s role, as he or she needs to make sure that each scene ends in a clear lesson for the players in what sorts of actions will lead to victory or defeat. If the players—through their characters—confound the narrator’s idea of how the scene should play out … well, perhaps he or she has assessed their abilities (attributes, skills, and drives) incorrectly. Fun times!

This does not mean that the narrator has to plan out everything beforehand, deciding what will or will not lead to the characters’ victories. Sometimes, just as in the writing of a novel or screenplay, the story imposes its realities on both the players and the narrator. The scene must be rewritten!

The narrator is the steward of the story’s reality. Sometimes the narrator needs to recognize that his or her calculation of the characters’ strengths and weaknesses has been misguided. When this happens, the narrator needs to quickly recalculate, readjust, and rewrite the larger situation. NRP’s typology of scenes is intended to aid the narrator in this effort and permit the players greater freedom in following their characters’ drives.

ACT, EPISODE, AND FRANCHISE. Following the pattern established above, an act is a series of several scenes, and an episode a series of 3-5 acts. All games played in the same setting can be generally referred to as being in the same franchise, although this is unlikely to come up unless the players or narrator tire of the setting.

As with scenes, at the end of each act and episode there is either a lesson for the players about the story or a lesson for the narrator about the characters and players.

As a clue to narrators, a gaming session should consist of a single act, several scenes moving the narrative forward within a multi-session episode. This breakdown gives the narrator a chance, between game sessions, to rework the episode’s situation if the characters (as diligently performed by their players) scuttle the script!

Character advancement from stage to stage should be managed by the narrator to extend over episodes. Elizabeth Swann and Samwise Gamgee rose from Beginner to Competent over three episodes, for example. The trilogy is an strong contender for an organizational level of episodes, in this regard; stories often gather themselves into groups of three to five.

Final words

As you can see, the core concepts of NRP are geared toward creating a greater focus on narrative and role-playing, emphasizing character drives and the role these play in the over-arching story. Players are rewarded mainly by playing their characters true, even if this leads to tactical defeats, under the guidance of the narrator who controls the overall story.