I have to confess a particularly deep connection to the events of 9/11. Not only was I scheduled to fly back to the mainland from visiting family in Hawai’i on that day, but I was working in counter-terrorism as an Arabic linguist at the time, I had studied Islam at university, and had foreseen this innovation in tactics years before while studying the origins of Wahhabi militancy.*

I have to confess a particularly deep connection to the events of 9/11. Not only was I scheduled to fly back to the mainland from visiting family in Hawai’i on that day, but I was working in counter-terrorism as an Arabic linguist at the time, I had studied Islam at university, and had foreseen this innovation in tactics years before while studying the origins of Wahhabi militancy.*

Recent developments have caught my attention again, as a writer: workers digging at Ground Zero have uncovered a ship dating to the 1700s in the muck under where the World Trade Center once stood. (See the Christian Science Monitor or Associated Press for the full story.)

The story of this ship is intriguing for many reasons. It reveals how pollution has actually made the world a better place for wooden ships, how New Yorkers used to be able to purchase land that didn’t exist, and how much an iron anchor from the period weighed, all excellent background material for historical fiction writers.

Follow one of the links above to read more.

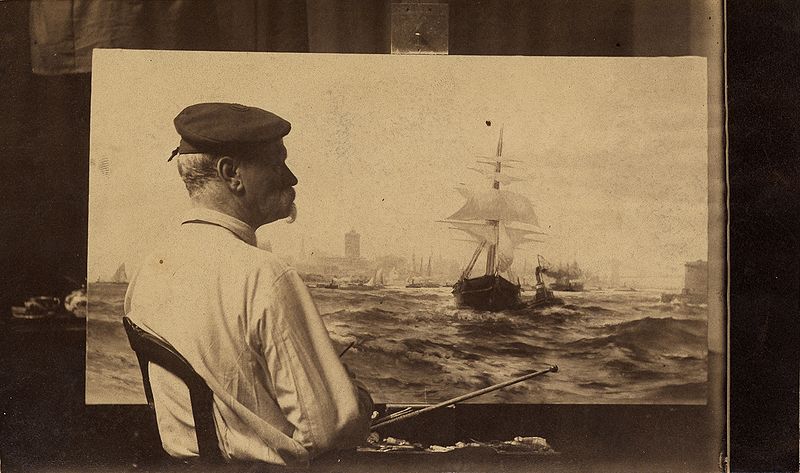

Edward Moran, who painted many maritime scenes, including of New York Harbor. By the time this photograph was taken around 1870, the WTC ship had already been abandoned to the muck for over half a century.

* For the full deets on the prescient notebook doodle I’m referencing here, ask nicely and I might blog about it.

From The Reshaping of Everyday Life : 1790-1840 (1988) by Jack Larkin:

From The Reshaping of Everyday Life : 1790-1840 (1988) by Jack Larkin: