Forensics is just archaeology without the wait.

Forensics is just archaeology without the wait.

Forensics is just archaeology without the wait.

Forensics is just archaeology without the wait.

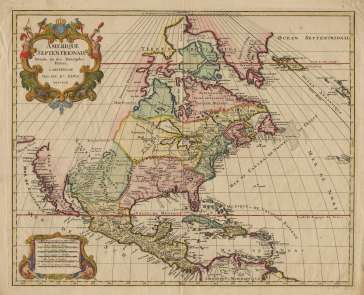

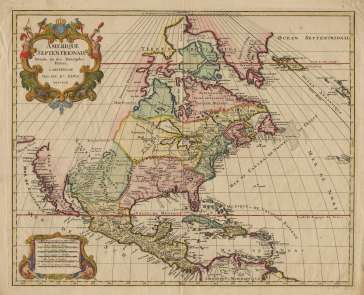

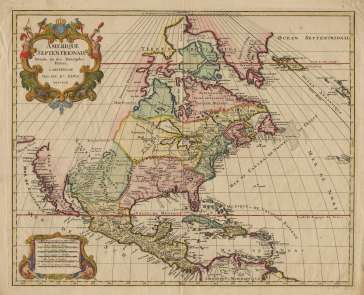

In the 1500s, along a wooded river near the sea, the Lenape people of the village of Chammasungh had farmed, hunted, and fished for generations.

In the 1500s, along a wooded river near the sea, the Lenape people of the village of Chammasungh had farmed, hunted, and fished for generations.

During the 1600s, however, Chammasungh was first renamed “Finland” by invading Swedes, then “Marrites Hoek” by the Dutch. Soon after, property records in the town record the arrival of The Proprietor, an ominous reference to William Penn, whose name we have inherited in Pennsylvania.

And, the both Lenape people and their river were renamed by colonists after the governor of Virginia, Thomas West, Baron De La Warr — or Delaware.

Digging in this little town on the Delaware River (now called Marcus Hook) has revealed a wealth of artifacts from this history, obscure to many Americans who typically look back no further than the Civil or Revolutionary wars. These treasures include plates with yellow-and-blue sunburst designs, British cannonballs, and a red quartz arrowhead dating from the time of Stonehenge, the Olmecs, and the most ancient Chinese dynasty.

I have to confess a particularly deep connection to the events of 9/11. Not only was I scheduled to fly back to the mainland from visiting family in Hawai’i on that day, but I was working in counter-terrorism as an Arabic linguist at the time, I had studied Islam at university, and had foreseen this innovation in tactics years before while studying the origins of Wahhabi militancy.*

I have to confess a particularly deep connection to the events of 9/11. Not only was I scheduled to fly back to the mainland from visiting family in Hawai’i on that day, but I was working in counter-terrorism as an Arabic linguist at the time, I had studied Islam at university, and had foreseen this innovation in tactics years before while studying the origins of Wahhabi militancy.*

Recent developments have caught my attention again, as a writer: workers digging at Ground Zero have uncovered a ship dating to the 1700s in the muck under where the World Trade Center once stood. (See the Christian Science Monitor or Associated Press for the full story.)

The story of this ship is intriguing for many reasons. It reveals how pollution has actually made the world a better place for wooden ships, how New Yorkers used to be able to purchase land that didn’t exist, and how much an iron anchor from the period weighed, all excellent background material for historical fiction writers.

Follow one of the links above to read more.

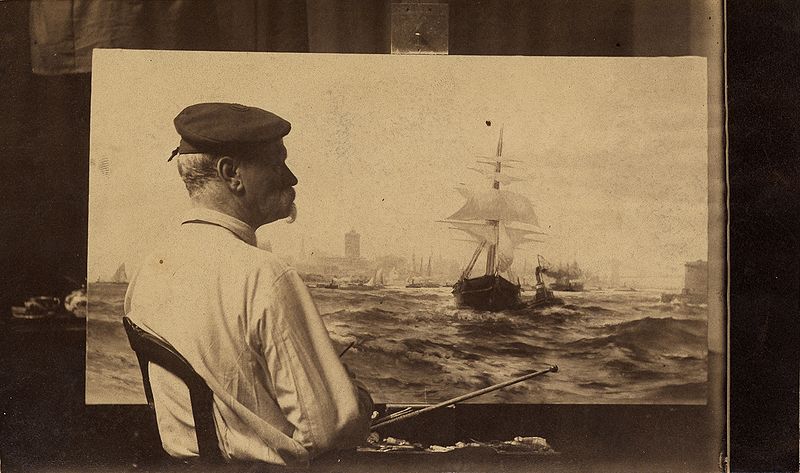

Edward Moran, who painted many maritime scenes, including of New York Harbor. By the time this photograph was taken around 1870, the WTC ship had already been abandoned to the muck for over half a century.

* For the full deets on the prescient notebook doodle I’m referencing here, ask nicely and I might blog about it.

Want to know how close we can be to the sort of conflict that drives good historical fiction?

Want to know how close we can be to the sort of conflict that drives good historical fiction?

For the residents of the coastal town of Mystic, Connecticut, it’s as close as their own front yards. On a hill that is now part of a quiet neighborhood, almost 400 years ago, a fort of the Pequot people was destroyed by English colonists.

As reported by the Associated Press:

Artifacts of a battle between a Native American tribe and English settlers, a confrontation that helped shape early American history, have sat for years below manicured lawns and children’s swing sets in a Connecticut neighborhood. A project to map the battlefields of the Pequot War is bringing those musket balls, gunflints and arrowheads into the sunlight for the first time in centuries.

It’s also giving researchers insight into the combatants and the land on which they fought, particularly the Mystic hilltop where at least 400 Pequot Indians died in a 1637 massacre by English settlers.

Often, Americans look for historical intrigue and suspense overseas, in the Highlands of Scotland, the Imperial Court of China, India under the Raj, or among the legions of Rome.

But, long before the familiar struggles of the Depression, Prohibition and its gang wars, the Old West, the Civil War, and even the Revolutionary War, the eastern shore of America was the setting for much romance, violence, friendship, and betrayal… all of the elements that make up a good historical novel.

The Guardian Science/Anthropology: “First Britons may have used clothes, shelters and fire to ward off cold”

The Guardian Science/Anthropology: “First Britons may have used clothes, shelters and fire to ward off cold”

Yeah, that would probably work better than just blowing into your hands.

_

Afterthought: What’s up, Guardian? No Oxford comma?

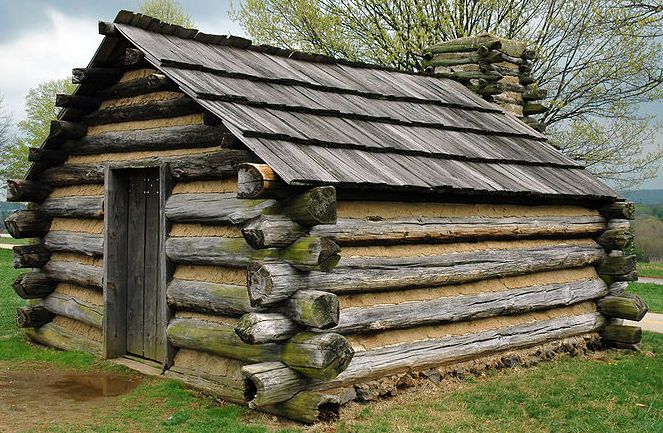

George Washington had it built.

George Washington had it built.

Martha Washington mentioned it in a letter to a friend.

And now, two hundred thirty-two years later, archaeologists have found it.

What is it? It’s a log cabin General Washington had constructed behind the main headquarters at Valley Forge, to use as a dining hall for himself and his top advisers. Archaeologists working for the National Park Service have now located it, having identified discolored earth that indicates the presence of the “sill log” that forms the base of a log cabin.

Washington, his aides, servants and wife all lived and worked together in the small headquarters house. To ease the cramped conditions in what some historians have dubbed the “1778 Pentagon,” the general had a cabin constructed. During the encampment, from Dec. 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778, British troops occupied Philadelphia. The cabin served as both a dining hall and war room for Washington and his men.

It is unknown how many critical debates took place in this tiny structure, debates that guided the fate of millions yet to be born, and pointing us to it was a single piece of correspondence from a woman to her friend.

One small cabin, one small letter. Sometimes, the little things truly are what count!

A replica cabin at Valley Forge, similar to the one archaeologists are now excavating near General Washington's headquarters.

There have been some interesting recent developments in the not-so-recent world of archaeology.

A site on the Patuxent river that not only yielded a Native American house from the age of the Crusades, but implements carbon-dated to 3000 years ago, and clues that could push the site’s antiquity back to 10,000 years BP.

And, interesting for those of us who love the little historical details, archaeologists have discovered what is believed to be the oldest leather shoe ever found, “about 5,500 years old, which is about 1,000 years older than the great pyramid of Egypt and 400 years older than Stonehenge.” The shoe was found in Armenia but, according to the story, the oldest footwear of all was found in the United States and made of plant fibers.

Finally, in news of a more nautical nature, an ongoing, 18th century dig site in Maine uncovers details about two of the first shipwrights in the region.

Beams believed to be from the water bastion of mid-18th Century Fort Edward have been dredged up, interestingly as part of clean-up effort aimed at removing dangerous pollutants from the bed of the Hudson River. Artifacts from the early encroachment of pre-Industrial civilization on the North American continent now have to be tested for industrial PCB’s just to determine whether they are safe for public viewing.

Beams believed to be from the water bastion of mid-18th Century Fort Edward have been dredged up, interestingly as part of clean-up effort aimed at removing dangerous pollutants from the bed of the Hudson River. Artifacts from the early encroachment of pre-Industrial civilization on the North American continent now have to be tested for industrial PCB’s just to determine whether they are safe for public viewing.

Fort Edward was the furthest navigable point inland on the Hudson, and therefore the beginning of “portage” or carrying goods and vessels overland from water to water. It is also known as the location where New Hampshire’s Major Roger Roberts wrote his famous Rules of Ranging.