Today I want to perform a philosophical genealogy, tracing today’s deluge of aspiring authors to the political and theological underpinnings of the Modern age.

Today I want to perform a philosophical genealogy, tracing today’s deluge of aspiring authors to the political and theological underpinnings of the Modern age.

Roll with me on this one; I rarely get to use my formal training in comparative religion here, and I promise this isn’t going to be a conversion blog or an Anne Rice-style rant. So, let me state up front that this is more about tracing the path of an idea popular among present-day book enthusiasts than promoting or dismissing any of its religious or political ancestors.

_

If It’s Good Enough For Grandpa

The “priesthood of all believers” is the idea, often attributed to Protestant reformer Martin Luther, that everyone has equal access to the Creator, regardless of their role in the church.

Luther never actually used the phrase, however.

The Divine Doodoophage

In a piece called To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (a sort of Renaissance blog rant), Luther asserted only that there was no spiritual difference between lay believers and priests, while maintaining a distinction in the office of priest. This implies Luther believed that, even though everyone has equally direct access to the Creator, some are still better suited to performing professional duties relating to that access, based on their specific talents or gifts (χάρισμα in New Testament Greek).*

Nevertheless, a very generic and unsophisticated misreading of Luther’s idea—i.e., the “priesthood of all believers”— which lacks his qualifications about individual ability, still holds sway not only in Protestant circles but beyond the bounds of Christianity and throughout Western culture. Today, we hear its echo in “everyone is creative” … with the mute button tapped right before you get to the part about not everyone being equally gifted in drawing on and shaping that creativity.

Everyone has muscles, too, but does that make everyone an athlete? Of course not.

The “priesthood of all believers” is a very idealistic and democratic notion, and it feels good to believe in, because it means that even the most casual coffee shop philosopher is just as qualified to opine on divinity as someone who has a lifelong natural affinity for theology honed by many years of training and education.

_

The Strange Bedfellow

Moreover, with freedom of religion and freedom of speech legally guaranteed in nearly every industrialized nation on Earth, the inapplicability of expertise has virtually become a dogma itself in some circles, even though that was never the intent of enshrining these rights in law.

“Everyone has a right to their opinion” is often used as a euphemism for “everyone’s opinion is equally valid.” These two are not, however, equivalent propositions. The former is (as Ben Franklin asserted) “self-evident,” while the latter is self-evidently absurd.

“Everyone has a right to their opinion” is often used as a euphemism for “everyone’s opinion is equally valid.” These two are not, however, equivalent propositions. The former is (as Ben Franklin asserted) “self-evident,” while the latter is self-evidently absurd.

In fact, a misunderstanding similar to the one surrounding the “priesthood of all believers” skews our views on the founders of American democracy, free speech, and freedom of religion. For example: Thomas Jefferson certainly wrote that “all men are created equal” in a political sense, “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” but he also believed fervently in a “natural aristocracy” grounded in “virtue and talents.”**

The political assertion that “all men are created equal” does not mean “all are created Senator” or “all are created judge” any more than Luther’s assertion of the spiritual equality of all believers means that he thought everyone is qualified to act as a minister.

Nevertheless, this misreading spans the entire gamut of culture from religion to politics and, I would argue, art.

_

Mistory Repeats Itself

In 20th century America, Protestant theologian James Luther Adams expanded the idea of the “priesthood of all believers” by adducing a “prophethood of all believers.” Unlike Martin Luther, James Luther actually used the phrase attributed to him, but he hardly meant by it that every member of a congregation was equal to, say, Moses or Jesus or Muhammad.

What he meant was that those who hold church office should see the entire lay community as engaged in ministry, or prophecy, communicating a moral message to the world under the official minister’s guidance. “The trained minister should as it were take the congregation along into the pulpit.” (from The Prophethood of All Believers, James Luther Adams)

Note that there is still a leader, and he is “trained.” The prophethood of all believers is a community accessing the Creative under the guidance of the minister, not everyone acting as his or her own minister. In fact, Adams specifically decried the “fissiparous individualism” which had become a hallmark of certain strains of religion and politics of his day, and saw it as undermining progressive efforts to promote justice and defend against corruption and evil.

Having witnessed firsthand the unimpeded growth of Nazi Germany during the years leading up to World War II (he spent a lot of time in Germany befriending anti-Nazi thinkers like Schweitzer and Barth) Adams certainly knew what he was talking about.

So Adams’s “prophethood of all believers” means the entire community taking an active role in doing good and spreading the word, while the ministers—rather than facing the congregation—face outward with the congregation.

It certainly doesn’t mean everyone a Messiah unto himself, a scattered crowd of gurus all trying to convert each other.

_

Everyone Has a Book in Them

The literary manifestation of this “scattered crowd of mutually converting gurus” is today’s writer-saturated literary world, wherein over half of Americans have not read a book in the past year (see Rachel Donadio’s “You’re an Author? Me too!”) yet more than 80 percent of them believe they have a book inside them that they should write (see Joseph Epstein’s “Think You Have a Book in You? Think Again”).

To put it bluntly, that writer-reader ratio just won’t work.

Granted, this is partly driven by the consumerization of writing, the purposeful engineering of demand for writing advice through “everyone has a book in them” marketing, a practice that is one of several factors threatening to transform publishing into a pyramid scheme. If you want a first-hand vision of this consumerization in action, just Google the phrase “everyone has a book in them” and scan through the list of entrepreneurs hoping to make a buck off that highly deluded optimistic 80+ percent.

We could call this phenomenon the “authorhood of all readers,” except that many aspiring authors aren’t really all that readerly in the first place—similar to how many self-anointed priests, prophets, and pundits eager to share their opinions on religion, politics, and economics haven’t really spent a lot of time studying those subjects.

Now, my point is not to condemn self-anointing or—let’s be more charitable—individual initiative. Not everyone who wants to write a book needs an MFA (in fact, many would discourage it) just as not everyone who demands respect for their economic ideas needs a Masters in finance. Or, for political opinions, the bar exam. Or, for religious ideas, ordination.

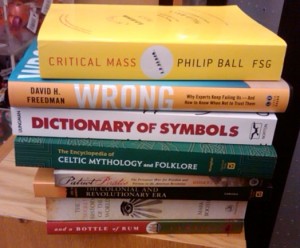

But, for crying out loud, at the very least you should read … a lot … first.

Books : not just for writing, also for reading!

In all of these cases, there is a community into which one has to read oneself (or listen, a primitive but nevertheless valid precursor to reading) before one should even consider the prospect of nominating oneself as a source of information rather than a beneficiary of it. And, in order for a given community to prosper, the beneficiaries of information have to outnumber the sources.

You can’t have a church where everyone is preaching from their own pulpit and nobody is in the pews.*** There would be no con-greg-ation (Latin for “gathering together”) and therefore no church, no community, no message, and no real ministry.

In the literary community, the readers are the congregation and the message is the value of good literature. Sure, we might not all agree on what that is, but that’s why we have different schools of criticism, different genres, different denominations of the literary, different “peoples of the book” to borrow a phrase from Islám. Each of these denominations, however, needs far more laymen than clergy.

Shirley Dent at the Guardian‘s Books Blog makes this point, while commenting on Joseph Skipsey’s definition of a great poet as someone with the “rare ability” to utilize a literary culture built on familiarity with the literature of the past:

Instead of peddling the lie that we are all authors now and that the only tale that matters is our own, why not put trust in that literary culture? Beyond the individual … society needs to believe in and recognise great literature. This belief is about reading not writing …

Note that neither Dent nor I are talking about some narrowly defined elite literary culture. This isn’t Lee Spiegel ranting. We’re talking about literary culture defined broadly as “people who read.” This may seem like an absurdly obvious definition, but not so much when 56 percent of people haven’t read a book this year, yet 80+ percent of them think they should write one.

Instead of a community of readers among whom a select few also become writers, we have the misapplied democratic ideal that everyone is equally endowed by Creativity with an unalienable right to become a published writer. A crowd of chiefs with no warriors, a kitchen crowded by chefs with no diners, a pulpit crowded with preachers with no pewsters.

It’s not exactly the “priesthood of all believers”—that is, the mistaken interpretation of Luther that everyone can act as ministers—but the idea is the same: since everyone is undeniably linked to creativity in some degree, go ahead and assert your writerhood and never mind those who ask (as Joseph Epstein does):

Why should so many people think they can write a book, especially at a time when so many people who actually do write books turn out not really to have a book in them—or at least not one that many other people can be made to care about? Something on the order of 80,000 books get published in America every year, most of them not needed, not wanted, not in any way remotely necessary.

Put frankly, the idea that everyone has a (read-worthy) book in them is at best a fantasy, a mass delusion. At worst, it’s a mass fraud perpetrated by unscrupulous peddlers of publishing advice.

But, most importantly, Epstein points toward the real key to a healthy publishing industry: books which are needed and wanted by readers, and which help to maintain a reading community. This is the only sustainable business model for publishing.

But, most importantly, Epstein points toward the real key to a healthy publishing industry: books which are needed and wanted by readers, and which help to maintain a reading community. This is the only sustainable business model for publishing.

Sure, there’s a lot of money to be made selling stuff to writer-consumers, but in the long term the “authorhood of all readers” spells bad news for publishing because it shifts the very nature of demand away from the certainty of (a) being a reader who buys a product that keeps publishing alive toward (b) the long-shot of being a writer who produces a product that most likely nobody will be willing to buy.

Eventually, this dynamic leaves you with a whole bunch of people who want you to publish their novel, but who can’t be bothered to buy anything you’ve already published. Not only is “everyone has a book in them” a long-shot for the aspiring author, it’s self-sabotage on the part of agents and publishers.

And, if this long-term consequence sounds too much like Chicken Little (or the much-maligned Malthus), consider the immediate effects of encouraging everyone, regardless of innate talent, that they should write a book. Flooding the manuscript pool with garbage makes participating in the publishing biz harder for everyone: good writers have a harder time being seen above the swarm of wannabes, while agents and publishers find themselves faced with slush piles that soar in quantity while plummeting in quality.

To put it in economic terms, it reduces the efficiency of every single process between a good writer’s inspiration and the reader’s bank account.

So, let’s take Dent’s advice and stop “peddling the lie” that we all have a book in us. Not only is it misguided economics, based on misunderstood politics, based on misinterpreted theology, but it leads to just plain miserable literature.

_

* The source text for the doctrine on “gifts” is in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians. I’m not going brave a thorough exegesis here, but I will reproduce the relevant passage so the reader can see how it clearly balances universality with diversity: “There are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit; and there are varieties of services, but the same Lord; and there are varieties of activities, but it is the same God who activates all of them in everyone.”

** Jefferson contrasted this “natural aristocracy” of “virtue and talents” against an “artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth.” The implications and consequences of this “artificial aristocracy” on the publishing business, or any business, would require for its full exposition an entire book of its own.

*** There is a joke about Unitarian Universalists, the group into which James Luther Adams’ Unitarians were absorbed in the 1960s. Q – Why are Unitarian Universalists so terrible at singing hymns together during church service? A – Because they’re all reading ahead to see if they agree with the words.

Cortnee Howard

August 12, 2010 at 10:38 am

You hit the nail on the head with your last section about everyone (not) having a book in them. I also think that industry plays an often subtle, but equally important part in this whole mess as well. Distribution giants like Amazon, make absolute sack loads of money by telling would-be writers everywhere that they are proverbial “special snowflakes” and need to be published for free immediately. And now that Bowker has launched a manuscript distribution service, I’m curious whether the good writers that you speak of will be able to find a publishing home or if a tidal wave of so-so manuscripts will clog the system and make everything worse.