Patrick Kiger at the Second Act blog published a list of seven literary one-hit wonders in honor of the 50th anniversary of the publication of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Patrick Kiger at the Second Act blog published a list of seven literary one-hit wonders in honor of the 50th anniversary of the publication of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Since these are seven broadly praised books which also share the distinction of being their authors’ only work, I thought it might be instructive to take a look at them to see if I could find any other similarities. What I discovered was that none of these books followed the “way things work” process from an unpublished writer’s hand to the bookstore shelf.

_

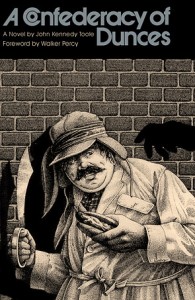

1. John Kennedy O’Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces. O’Toole committed suicide in 1969 with Dunces unpublished. His mother destroyed his suicide note, but was convinced his suicide was due to his failure to see his novel published. Making it her personal quest to get Dunces on bookshelves, she succeeded in 1980 only after having it rejected by eight publishers and literally forcing it into the hands of a published author. Dunces was received with worldwide acclaim, and won the Pulitzer in 1981. Ironically, the title of this novel is derived from a Jonathan Swift quote: “When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign, that the dunces are all in confederacy against him.” No s###.

2. Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind. Newspaper worker Margaret Mitchell’s friend Lois Cole recruited her to show Macmillan editor Harold Latham around Atlanta looking for up-and-coming Southern authors. At the end of the tour, Latham asked Mitchell if she had ever written a book. Even though she had, Mitchell humbly told him she had not. But, after hearing someone scoff at the idea that she could have written a book, on an angry impulse she handed Latham the manuscript for Gone With the Wind for consideration. Later, she tried to rescind the offer, but Latham was already convinced it was a best-seller from the little he had read. Wind also won the Pulitzer, and was adapted into the highest grossing film of all time. But, if not for the purely accidental social connection to Latham, his off-hand question, another person’s off-hand insult… I think you get the idea.

3. Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man. Here, I have to be more explicit about the threads tying Kiger’s examples together. Ellison’s book did not suffer the trials of Dunces on its way to publication, but Ellison was already writing book reviews and therefore even better connected to the publishing biz than Mitchell was. The story of the publication of Invisible Man provides the still-unpublished best-seller-worthy author (or the break-out best-seller seeking agent or publisher) little guidance.

4. Ross Lockridge, Jr., Raintree County. Lockridge dumped the manuscript in the Houghton Mifflin lobby in a beat-up suitcase. Sure, this was the 1940s, but still. Legend has it that Lockridge was so confident of Raintree‘s value that he was completely unsurprised that HM picked it up for publication. Damn straight.

5. Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar. Although undeniably a classic, as a roman à clef I have to disqualify Jar from a list of novels, with apologies to Kiger. Moreover, Plath published enough poetry that it’s hard to consider her a one-hit wonder. Even though one could use Jar to strengthen the case being made here, by making the same argument for her as for Ellison (she was pre-connected to the publishing world), I still judge a thinly veiled autobiography as not qualifying strictly as a work of fiction.

6. Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights. Emily’s father, Patrick, was a published author. ‘Nuff said? Okay, maybe not the most famous author in England, but a) published and b) author.

7. Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago. Pasternak was already a published poet when he wrote Zhivago, which was rejected for publication by Soviet authorities and had to be smuggled out of the country to be published. The lesson here being what? Be born under a repressive regime, publish some poetry, write a book that gains underground notoriety by being rejected by Communist censors, etc. etc.?

Notice the common theme? In none of the above cases did an author with no connections to the publishing business submit a manuscript through “official channels” to have his or her later-acclaimed novel published as a result of the expert vetting of agents and publishers. Not selected for that purpose by Kiger, his list nevertheless provides a little perspective on the proverbial “way things work.”

Significantly, the inspiration for Kiger’s list, Harper Lee, was a childhood friend of the famed Truman Capote. Talk about a foot in the door!

Significantly, the inspiration for Kiger’s list, Harper Lee, was a childhood friend of the famed Truman Capote. Talk about a foot in the door!

More often than not, I complain that publishing professionals encourage aspiring authors too much, creating an overconfident, over-aggressive swarm of glory writers. But, the flip side of encouraging the wrong writers — who will simply clog slush piles with their unpublishable dreck — is the danger of missing the great writers by failing to turn a critical eye to the status quo process a book must follow from conception to publication.

How many O’Tooles out there commit suicide in despair, their Pulitzer-worthy masterpieces never seeing the outside of a box of effects? How many Mitchells never stumble into the series of coincidences that led to the publication of Gone With the Wind? How many Raintree Countys are tossed out because they were incorrectly submitted? [UPDATE: Tossed out or exploded by police?] How many Ellisons and Plaths and Brontës and Pasternaks don’t have pre-existing connections to publishing?

How many best-sellers … no, let’s be more practical … how many best-seller dollars are simply thrown away because the process isn’t really designed to produce optimal outcomes? How often is our literary culture robbed of masterpieces by weaknesses of The Process?

While we ponder the future of paper books, self-publishing, and agent pay models, we might also take a look at the process to uncover the reality that selection bias excludes from our casual consideration: the truly great books agents and publishers might never see or take seriously.

Veda

July 11, 2010 at 12:37 am

The publishing world certainly isn’t exempt from the Oligarchy that seems to plague the world. In fact, it’s a perfect example. It’s all about who you know.

Jamieson Ridenhour

July 17, 2010 at 7:18 pm

In general, you’re on the money with your assessments here. With Emily Bronte, though, I’d have to say that her originally publishing her novel under an assumed (male) name (as did sisters Anne and Charlotte) would preclude any influence from her father’s small and relatively unsuccessful collection of poetry.