CHAPTER ONE

KINGS COVE

“Bring the transport on deck.”

“Bring the transport on deck.”

The quartermaster cocked his stubbly jaw. “Sir?”

Captain Durban lifted his hat by its front peak and brushed his hair back. His eyes were steady on the wooded hills of the coast ahead, specifically a breach in that line of green.

“I want that motherfucker off my ship before he stirs up more mischief.”

The quartermaster nodded and scanned the deck. He lifted his gaze to the gap in the hills. The ship was tacking too far to starboard.

“Mr. Skilling,” the quartermaster said, turning. Mr. Skilling wasn’t at the wheel. He was standing just behind a new sailor whose name the quartermaster hadn’t committed to memory. The quartermaster nodded at the boy.

“A few points to port, jack.”

Skilling peered over the boy’s shoulder at the course ahead. “It looks—”

“It’s not,” the quartermaster said. “A few points to port, please.”

The sailor’s lips fought against each other, but he nodded.

“I’ll make sure the sheets are proper,” Skilling grumbled and descended to the weatherdeck.

“So,” the quartermaster turned back to Captain Durban. “If you want him off the ship, why thread the falls?”

“The sea told me.”

The captain glanced at the waters rushing by the ship, as if to prove a point. The quartermaster had seen this theater before. Durban was a man whose own judgment was the only judgment that mattered. He assumed all right-thinking people would agree and, consequently, disagreement was a flaw of intellect or morals.

“After such a long voyage, we could have arrived at any point in the tide. We arrived at high slack. The falls will be drowned. The sea is inviting us into Kings Cove.”

That rang a bit superstitious to the quartermaster, but he had learned not to argue with superstition. Particularly Waltier Durban’s superstition.

“Fair, but the governor’s plantation docks are closer, and on the bay side. And, there’s the canal.”

The captain scowled and grunted at the quartermaster.

“I’ll not pay the governor’s fucking tolls. God-damned bloodsucker.”

The quartermaster stifled his head from shaking until the captain looked over the bow again. He knew there was no argument to shift their course.

“Mr. Skilling!”

The man looked up to the quartermaster, having set the crew to adjusting the sails.

“Bring Mr. Arland on deck. In shackles, if you please.”

After Skilling trundled belowdecks, the captain and quartermaster scanned the choppy waters of St. Vincent’s Bay. Dolphins were leaping from the water chasing a school of grayfish. Gulls swooped to pick minnows from a patch of drifting seaweed. There were several sails funneling toward the drowned falls, to risk the swirling waters and enter Kings Cove on the cheap.

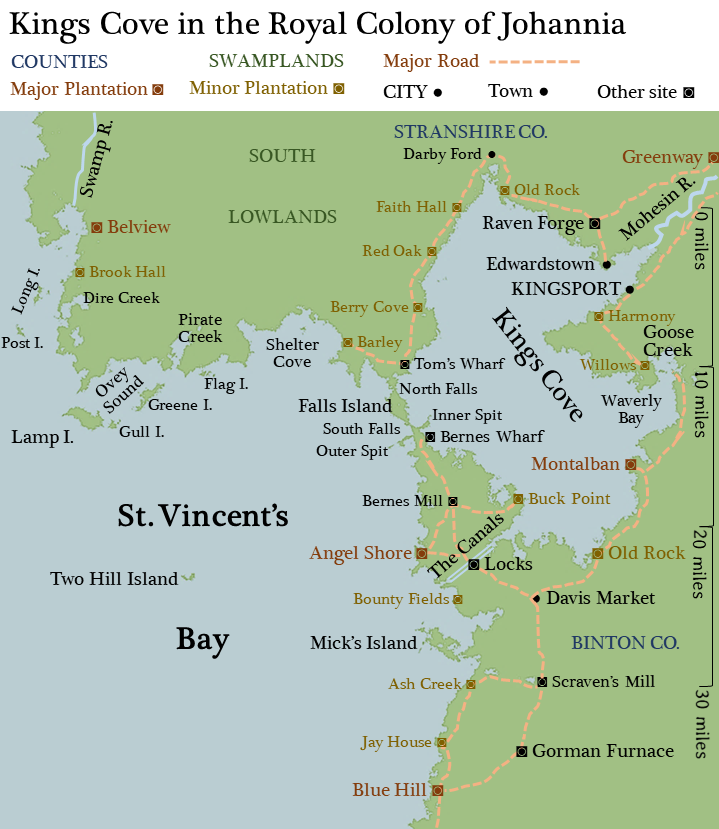

The quartermaster never understood why the cove colonized by the king’s men was not King’s Cove. But, on the maps, always Kings Cove. Same as the king’s port, Kingsport.

On the map, the breach ahead of them was the South Falls, the North Falls being three miles north at the other end of Falls Island. Both were cataracts during low tide, when the waters of Kings Cove poured into the sea. During high tide, they were drowned by the sea, which rushed into the cove at depths safe for all but ships of the deepest draught. South Falls breach was the widest, and thus the most popular.

But, the waters of the South Falls inlet were still treacherous as the tide rose or fell above the drowned falls, swirling and racing through a breach less than a quarter-mile wide, with walls of jagged rock to either side. High slack was better, even though there were still eddies. With a good wind, one could slip through the breach and dock at Kingsport without paying the tolls on the canal or the roads, which were the private property of Governor Willam Bernes.

Timid captains would simply pay the toll to take the governor’s canal into the Cove, or dock at the governor’s plantation, Angel Shore, and pay the toll to have goods transported overland to Kingsport.

The quartermaster knew Durban was not a timid captain. He regularly sailed past their country’s mid-ocean outposts on the Isle of Eana, making a trans-oceanic passage without resupply, in order to cut a few days, maybe a week, off his journey. The crew complained of the dry bread and over-salted pork, but Durban wasn’t paid by the crew.

This cruel discipline had worked well for Durban, until Raf Arland was dumped on his ship as a criminal condemned to transport to the colony of Johannia.

Skilling climbed onto the weatherdeck from below, dragging a shackled man behind him. The man was wearing a soiled cotton shirt, red velvet vest, and dark green pants. His curly blonde hair swung around his shoulders. He looked over his shoulder at the captain and grinned.

“Good morning, skipper!”

“It’s afternoon,” the captain growled. “And nightfall for you.”

“Take him forward, Mr. Skilling,” the quartermaster said.

Captain Durban tugged at his long coat.

The quartermaster cleared his throat. “And, keep Mr. Arland from talking to the crew.”

Skilling nodded and yanked at Arland’s shackles. The transport chuckled at that and started saying his hellos to the crew as he passed by. Skilling warned him to shut up.

“Mr. Schank,” the captain growled. “More sail.”

“Yes, captain,” the quartermaster said. He repeated the order to the men on the deck.

“It’s only by my infinite mercy that man doesn’t have conspiracy to mutiny added to his crimes.”

“Yes, captain,” Schank said.

He knew the real reason was that Durban did not want to cross the governor, who had requested Arland by name. A mutiny charge would see the man hanged in Kingsport. It was unclear how Governor Bernes would react to that, but Schank was sure it would not be good for the captain.

“I want him off of the Dolphin before the lines are secured.”

“Yes, sir. I’ll have him thrown over the gunnel onto the dock.”

He took in Durban’s countenance, which was not encouraging.

“Brusquely,” the captain said.

He cracked his neck and straightened his long coat again.

“Nobody calls me skipper.”

∞

Julius Blake stepped out of his carriage, polished leather boots crunching against the pink gravel. The driver and the bagman standing at the boot kept their places, not assisting him, as he had instructed.

The sun was low over St. Vincent’s Bay. The lawn leading down to the docks was lined with cedars, the spreading limbs shading the grass and gravel road below. Birds flitted from tree to tree and Blake noted a tuskrat scurrying from one side of the road to the other.

The house at the top of the slope was red brick with white granite corners, two-and-a-half floors, seven bays, and seven dormers looking out over the slope. A fairly grand plantation house, Angel Shore, fit for the governor of the Royal Colony of Johannia.

Governor Willam Bernes, a man of contentious reputation. A moral man who had fought on the frontier in the militia. A wise man who had bought good and arable land on the peninsula separating Kings Cove from the open sea. An ambitious and practical man who had built roads, canals, and built his own career from militia service to the colonial governorship—which he had held for twenty years.

Blue-liveried footmen from the house rushed out to gather the property strapped to the back of the carriage as the bagman unfastened it. Julius walked past them to the staff manning the porch.

A man in black livery stepped up as Julius climbed the granite stairs. Clearly, the governor’s butler.

“Mr. Blake, your room is—”

“Have someone show me.”

“Yes, Mr. Blake. I will show you.”

“Thank you. It’s Lord Blake, now.”

“Apologies.”

Julius nodded and kept climbing the stairs.

“None necessary. I was only elevated at Crossing plantation two months ago.”

The butler scrambled up the stairs to keep pace.

“Congratulations, my lord.”

Blake waved at the house they were entering.

“Crossing only has five bays, but fully granite construction.”

“Yes, my lord. You’re nearer the quarries on Wild River.”

That was a clever gambit. The butler was recognizing Crossing’s superior construction while putting it in geographic context so that the governor could save face. Blake decided that he liked this butler.

They stepped into the foyer of Angel Shore house, a central hallway that separated the first floor north and south. The walls were papered in a floral, mustard Coromello print, bright blue chairs along the sides. At the far end of the hallway was a grand stair with dark wood banisters decorated with pineapple carvings. The rear doors were closed, their ample windows revealing a Zonaru cherry orchard dark pink in a late autumn bloom.

Julius paused at the foot of the stair.

“The governor is not here to greet me?”

The butler looked at his black leather shoes.

“Lord Bernes is at the Locks, inspecting them and the bridge.”

“Making sure the tolls are properly gathered.”

The butler shrugged. Intimidated or embarrassed by Blake’s candor. A servant man. Julius felt sympathy for the man’s subordination. Only ten years before, he was a subordinate, a private in the colonial militia, enlisting to escape a life of drudgery on the docks of Kingsport.

He had proven himself in the woods of Stranshire County by killing a rampaging Tauri bandit in the Sweep River valley, a notorious bull-man known as Black Horn. Promoted to lieutenant, he had scoured the Bressian Reach of Orsar bear-men, clearing the trails that Marchian trappers used to sneak furs through Relles Pass from the hunting hills of Colchassen to avoid inter-colonial tariffs.

Blake had climbed from filth to feudal title by the point of his saber and the flint of his guns. Willam Bernes had started the son of a lord; Julius Blake had started a wharf jack. But, he knew the adventurer’s path he’d followed wasn’t equally open or tempting to everyone, particularly a butler with a comfortable position in a governor’s house. Honor required he give this subordinate man his dignity.

“You’re in the lead, sir,” Blake said with a broad sweep of his hand. “This is your kingdom. I shall follow you to my quarters.”

The man grinned at that, and climbed the grand stairs ahead of Lord Blake.

The room was well furnished. A four-post bed draped in yellow silk. A mahogany dressing desk with a silvered mirror. A porcelain chamber pot decorated in futile orange vines. An oil painting of a bark at sea, its sails taut on a starboard tack, the sky warning of a storm. The single window would shine the morning sunlight at the foot of the bed, not the head. Well placed. A plastered fireplace had intricate carved details portraying a hunting scene.

“I’ll need a bath. The road from Crossing was long.”

“Of course, my lord.”

“And, after the bath, I’ll want to meet whoever is here at Angel Shore.”

“Yes, my lord.”

∞

The sun was low behind them as the breach between Falls Island and Bernes’ peninsula began to show the broad, smooth waters of Kings Cove beyond. The low ridge of the Outer Spit was a dark buff-and-green line on the southern horizon, guiding them toward the falls.

Raf Arland leaned against the gunnel near the bow, his blonde curls tossed forward by the wind as he glanced back and forth, smiling, between the breach and the captain on the quarterdeck.

“I see some white in there, skipper!” the man shouted. “Tide’s falling faster than you expected!”

Schank could feel the captain tense at his side. He didn’t look. Instead he glanced over his shoulder at the new man at the wheel.

The sailor’s face was uncertain. Why had Skilling chosen a green jack to thread the falls? He must have had a reason. Skilling was a serious sailor.

Schank nodded at the man at the wheel to let him know to keep the course. Then, he turned to the weatherdeck. Mr. Skilling, his deputy quartermaster, was staring up at him, just as Schank knew he would be.

“Sails as set, Mr. Skilling!”

“Aye, Mr. Schank. But, you see!”

The man waved to port and starboard, sweeping in the sails of other vessels also closing on the breach.

The quartermaster dared the captain’s attention. Durban was nodding, his lower lip a mountain of barely suppressed rage.

“Mr. Skilling!” Schank said. “Belay my last! More sail, same course. Let it all out. The wind’s strong, but we can replace damaged poles at Kingsport. The sooner we’re through the breach the better.”

The deputy quartermaster nodded, then found a grin somewhere in his obedient resolve.

“Hear that, boys? Let’s beat those other bastards to it! It’s a race!”

The men ayed and huzzahed as they rushed to-and-fro across the deck, some scrambling like mad up the shrouds. Their enthusiasm spoke to their trust in the captain’s competence. Despite the disturbances caused by Raf Arland, the men were still the Dolphin‘s men.

Sails slapped the air and poles groaned as the deck jerked forward under their feet. Schank turned to the captain, who was still nodding and angry. His eyes weren’t on the breach, though. They were on Raf Arland’s happy face.

“He’s a mean trouble, no doubt, captain. But, we’ll soon be rid of him.”

Durban’s head tilted left and right.

“You wouldn’t be standing next to me but for him.”

Schank cringed. The scandal Arland had caused between the lieutenants was now focused on him. Unfairly, the quartermaster felt.

“I was friends with Jim and Mike. Lieutenant Jim was my lord’s son.”

The captain sighed and leaned his face toward the quartermaster.

“And yet, if that transport hadn’t goaded my mates into a murderous wager on their wives’ fidelity, they’d both be here beside me instead of you. A mere quartermaster.”

“Captain.” Schank struggled to find the words. He was not an educated man. “I tried to talk the lieutenants out of that fool-worthy bet. They were…”

Durban played with the corner of his mouth with his tongue.

“What were they, Mr. Schank? I trusted those men. I selected them as my mates. What did you see in them that I did not?”

Schank turned his eyes to the breach between the hills. Arland was right. There was white on the water there. The wind would be fighting the failing tide and the Dolphin would be spun in the eddies. He scanned the other vessels. Half of them were already turning south, toward Angel Shore or toward the governor’s canal.

The quartermaster was at the end of his contract. Kingsport was his freedom, if he wanted it. The captain knew that. Maybe Durban was pressing him to leave the Dolphin. If so, there was no barrier to honesty.

Schank took a deep breath.

“Your mates were cocksure. They knew Arland was a rogue. They knew the wager was a trick. They saw the breach swirling ahead of them and they just barreled on through it.”

Durban chuckled and turned his eyes back toward the entrance to Kings Cove. His shadow stretched over the weatherdeck in the falling sun.

“You’re saying they underestimated our transport,” he said. “And so did you.”

Schank fought his shoulders, which wanted to slump. The captain looked at him again.

“Brusquely, you said.”

Schank nodded. “Brusquely, I meant.”

∞

Blake sat, appropriately enough, in the sitting room of Angel Shore house. The walls were red velvet, the floors polished pine, the mantle gilded in an ostentatious yet poor imitation of Coromello luxury.

Blake had visited genuine Coromello houses in Margara. Their gilding was spare and elegant compared to the gaudy display of Governor Bernes’ sitting room.

The ornate table in the center of the sitting room supported a porcelain tea set, from which Blake was drinking, a stacked deck of cards, and a folded board with green and yellow Saints War pieces arrayed on top.

Julius Blake was wearing a uniform he had designed. His winter gear, appropriate for the ranging season to come. White linen, insulated with down padding, with black accents.

Perfect for hiding in the snowbound forests of the Bressian Reach where Blake had built his reputation. Legally the property of Marchian colonies, by treaty, the Reach was made up of the foothills of the Provinian Mountains to the north of Johannia. Johannian militia were tolerated by the Marchians to help maintain order and protect the Marchian coasts from Orsar and Tauri raiders.

Though this arrangement was ostensibly to suppress the mongrel races, in fact it secured the illicit connections Governor Bernes had with rogue Marchian trappers from Colchassen who braved Relles Pass through the Provinians to avoid the tariffs the Marchian colonies to the north imposed on the fur trade.

Surely that was the mission that the governor had in mind when inviting him to Angel Shore. Patrol the Reach and secure Johannia’s profits.

“Lord Blake.” The butler stood stiffly just outside the door to the sitting room.

“Yes. Come.”

“This is the daughter of Governor Bernes, Lady Snow.”

A woman stepped into the doorway. She was adorned in an elaborate gray dress trimmed in red fur. A winter’s dress, although it was still autumn, the red fox fur a defiance of the season. Winter foxes would be turning white as the air chilled.

Her skin was as pale as her name, her eyes pine green, her hair a red crown braided over tender ears. She was a vision of winter.

“Lord Blake, do you play at cards?”

She had a pink smirk that could snare an oathed hermit.

He smiled and set an elbow on his knee.

“I do not. The complications confound me.”

She nodded and turned an eye to the butler. He bowed and stepped backward into the foyer hallway.

“You’re a man who prefers simpler odds.”

He looked to the windows, through the black silk drapes, where the sky was darkening from purple to black. The flames of the fireplace danced against the velvet walls.

“I am a man who prefers simplifying the odds. Do you play at Saints War?”

Her face was placid in a practiced fashion.

“I do not. But my friend, Grigarius, loves the board.”

Julius Blake was enjoying her game before the game. He chuckled and lifted his elbow from knee to table.

“Grigarius? A manservant?”

A form stepped into view behind Snow Bernes. A huge shape of black leather and brown fur and white smiling teeth. The bear-man stood a full two feet over the governor’s daughter. Blake felt the back of the chair press against his shoulders.

“Good evening, Mr. Grigarius.”

“Good evening, Lord Blake.”

The voice was like the thunder of a distant storm.

“You play at the board?” Blake forced himself to ask.

The corner of the Orsar’s maw lifted. Who knew these mongrels could enjoy a good banter? The giants of the north who had bred them must have instilled some dark, winter’s humor in their make-up.

“I do,” the bear-man sad. “Shall we play?”

Blake felt his cheeks stretch. His boots kicked two chairs away from the table. He scraped the Saints War pieces from the board with one hand and scooped up the deck with the other. With a flick of his elbow, he sent the cards tumbling into the fireplace. They glowed yellow in the orange flames.

Snow strode into the sitting room like a steady onshore breeze. She took the chair opposite Blake and nodded as she sat, straightening her dress.

Grigarius took the chair opposite the fireplace, between the two humans, his enormous frame settling into the seat like a thick post settling into a post-hole. It would take a squad of men to move that mongrel, Blake knew.

Julius unfolded the board and began arranging the pieces. A huge hand, clawed and brown-furred, closed over Blake’s. He looked up into the bear-man’s eyes. They were brown and resolved. Blake nodded and leaned back in his chair.

Grigarius placed the pieces with impressive precision, given the claws at the ends of his thick fingers. Snow Bernes grinned at Blake across the table, her head tilting gently left and right.

The board was set. The fireplace crackled.

Blake leaned on the table.

“Miss Snow, what’s the butler’s name?”

She grinned with curiosity.

“Mr. Leybold.”

The butler appeared, dutifully, in the doorway.

Blake smiled.

“Some drinks please, Mr. Leybold. Rye whiskey for me.”

Snow lifted a finger.

“White wine, Catarina vintage, please.”

Grigarius was staring at the pieces on the board.

“I will also have rye whiskey, with the lordling.”

Blake couldn’t stop himself grinning at that play on words. The bear-man was clever and political.

Leybold vanished into the house. Blake tapped two fingers on the table.

“First move? Green is traditional.” His own side of the board was yellow.

Grigarius looked to Snow, then to Blake, and nodded.

“Since humans were first created, you go first.”

“Fair enough,” Julius said. “Mind if I inquire into your history as I ponder my first move? Your presence here requires an explanation, yes?”

The bear-man set his clawed hands on the edge of the table.

“I know your history,” Grigarius said. “A dockhand who won renown by killing a bull-man. Black Horn.”

Blake nodded. He glanced at the governor’s daughter, who seemed to take pleasure in her servant’s unfolding of Blake’s history.

“You won a commission and set your sword and guns to ever more perilous foes.”

Blake frowned. It had just become personal.

“Bear-men, you mean.”

Grigarius nodded. His face was obnoxiously casual.

“Then your reputation sailed across the Apsamian Ocean to your homeland in Vincentia, and you won a lordship from your king.”

Blake glanced at Snow, who was placid and unreadable.

“Our king,” he said.

Grigarius grinned.

“And our king,” the bear-man said, “granted you a generous plot of land where the Wild River pours into the Mohesin, on which you built a grand house.”

Blake chuckled.

“Not as grand as Angel Shore.” He lifted his eyebrows at the governor’s daughter, who stared at the fireplace in response. “And you, Mr. Grigarius? What is your history?”

The bear-man drew in a long breath through his black nostrils.

“I was a cub, in an Orsar village along Relles Pass. The governor was but a captain then, leading men into the Provinian Range to secure trade with Marchian trappers.”

Lady Snow adjusted the furred neckline of her dress.

“Father was a different man, then,” she said. “The border skirmishes were brutal.”

Blake nodded. “They’re still fairly brutal.”

She looked at him sidelong and jerked her head toward the fireplace.

“Colonial militia were little more than savages then.”

“They killed everyone in my cavernhold,” Grigarius said. “Bernes urged their restraint, but his lieutenant…”

There was a moment, the firelight sending waves of amber against the velvet walls of the sitting room like a banner flapping in the wind. The world outside the windows was as black as coal.

“I’ve heard that part of the tale,” Blake said. Snow and Grigarius did not react.

“Captain Bernes brought charges,” he went on. “The lieutenant was retrieved to Vincentia without punishment.”

Grigarius drummed his claws against the table.

“The governor stopped the lieutenant at gunpoint,” the bear-man said. “But, it was too late. Everyone was dead by then. Everyone but me. Bernes brought me back to Angel Shore as a cub. Since then, he has had a strict policy of mercy toward us. Many of the cavernholds of the Sweep Valley now enjoy clemency from the colony.”

Blake nodded, with a glance at the governor’s daughter, who was still studying the fireplace.

“Insofar,” Blake said, “as they don’t disrupt the governor’s trade with rogue Marchian trappers moving through Relles Pass.”

Grigarius leaned back and took a deep drink of air.

“The board is set, Lord Blake.”

Julius nodded, studying the pieces.

“And we both know the rules.”

∞

The Dolphin yawed to port. The sheer cliffs of the South Falls breach were outlined sharply in the failing sun, trees swaying in the wind of the gorge, their long shadows against the rocks whipping like black banners.

Raf Arland stood shackled at the bow. He howled: “The seas are turning! How shall we sail?”

Captain Durban stomped against the quarterdeck.

“Mr. Schank,” he grumbled. “See us through the breach.”

The quartermaster nodded, but he was unsure. The eddies were strong. He turned to the green jack at the wheel.

“Hard to starboard!”

“Points sir?”

“Set us straight! Use your judgment.”

A green sailor’s judgment. Schank resisted the urge to throw the man aside and take the wheel himself. That would be an insult to the man, and to Skilling who had put the man there.

The captain abandoned the quarterdeck, stomping down the stairs. Good Lord and Lady, was he leaving the ship to his quartermaster, a man he wanted rid of?

Schank turned again to the sailor at the wheel.

“That’s enough. Turn as you feel needed. I trust your eye.”

The man took a breath and nodded.

Schank scanned the bay behind the Dolphin. All the other sails had turned south. This sealed the quartermaster’s intuition. They were on a lunatic’s course.

The ship realigned itself to the cove ahead, but the eddies pressed. The bow leaned dangerously toward the cliffs to the south.

Schank turned to the man at the wheel.

“Fifteen points to port. Stay your head, son.”

The sailor nodded, blinking but with surprising calm. Good man.

“Mr. Schank!” shouted the man shackled at the bow.

“Shut your gob, Mr. Arland!”

The man grinned at that.

“We’re going to make it through the breach! Your captain can unload his smuggled weapons at Kingsport instead of having them confiscated at Angel Shore.”

Schank felt his teeth grinding against each other. What an allegation! Both he and the transport knew the governor’s hunger for weapons and the captain’s hunger for profit. Bernes wanted to keep his frontier militia well-armed. Durban wanted his cargo paid for in full at Kingsport. Raf was playing another rogue’s gambit with the quartermaster’s honor.

“Mr. Arland, you’ll be happy to not be hanged for inciting mutiny!”

The transport grinned that annoying grin.

“There’s still time before we reach Kingsport to change the skipper’s mind about that!”

Schank knew that barb was aimed at his own waning loyalty. He had told Arland that his contract was up. The man was a natural manipulator.

“You’re destined for indenture to the governor upon our arrival at Kingsport. No better a fate for you than the governor’s guns. Think on that.”

Raf Arland nodded at the quartermaster’s resolve.

“I shall, Mr. Schank. I shall.”

The Dolphin came straight against the eddies, the white water and the cliffs of the breach falling away behind them. Ahead were the smooth, black waters of Kings Cove under the blossoming stars of evening.

Keep the course straight, and they’d be pulling up to the wharves of Kingsport before midnight. The only vessel to successfully brave the breach that day.

“Mr. Skilling,” the quartermaster shouted. The man stood erect among the sailors scampering around the weatherdeck. “Keep our course true around Harmony Point lighthouse to Kingsport.”

“Aye, Mr. Schank!”

“The quarterdeck is yours.”

With that, Schank trudged down the stairs to meet the captain in his quarters.