CHAPTER TWO

THE SHADOW TRADE

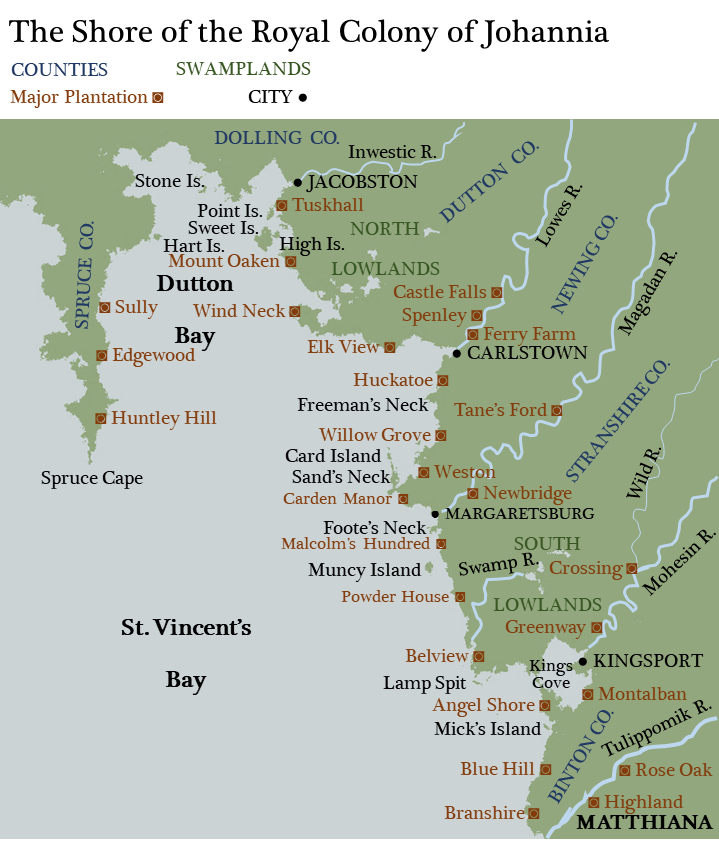

As the Dolphin pulled up to the lantern-lit docks of Kingsport, the men sleepily manning the docks took note of the ship’s approach and began laughing. Schank knew what they were laughing about, but he stared down at them grimly.

As the Dolphin pulled up to the lantern-lit docks of Kingsport, the men sleepily manning the docks took note of the ship’s approach and began laughing. Schank knew what they were laughing about, but he stared down at them grimly.

“We didn’t think anyone would be brave enough to thread the falls today!” one of the men shouted.

Schank broke. He couldn’t help grinning and nodding.

“But this is the Dolphin, boys!” The ship’s name made him suddenly glum. That would be the last time he spoke that name while on the Dolphin‘s crew. He waved his men to toss lines to the dockmen and stomped his way toward the bow. Mr. Skilling handed him the keys as he passed.

“Brusquely,” Raf Arland said with a grin.

Schank shoved the key into the shackle around the man’s left wrist and yanked the chains free from their post.

“Yes, brusquely.”

He unlocked the other shackle and tossed the chains, then the key, to Mr. Skilling. He grabbed the transport under his left arm and forced him to his feet.

“Do try not to kill me,” Arland sing-songed. “I’m promised to the governor.”

“Shut it.”

With a full-bodied shove, Schank sent Arland headlong over the gunnel. The man’s arms spun at his sides, his legs kicking. To Schank’s dismay and surprise, the man landed on his boots, as agile as a cat.

Raf Arland turned, grinning at the quartermaster with a casual salute of one hand.

“Grab that man,” Schank shouted. “He’s the governor’s transport.”

Arland offered his hands to the dockmen closing on him.

“Be gentle with me, boys. I’m for soft work.”

“No, he’s not,” Schank yelled. “He’s likely for the frontier.”

Arland looked up as short ropes bound his wrists roughly behind his back. “That’s news.”

The man was dragged off to the transports’ jail. That was done, or at least Schank hoped so.

He watched the remaining dockhands make fast the Dolphin‘s lines and drag a gangplank up to the gunnel. He stared up into the masts where the crew were brailing up the sails. He stared west over the dark waters of Kings Cove. It was a still expanse of moonlit water, without a sail in sight. A faceless expanse of blackness, reaching far back toward the inlet where untold sailors had lost their lives trying to thread those treacherous falls. The ghosts of decades of colonial ambition glaring back at him from the cold waters.

He shook off the ghosts, stepped over to the gang, gathered up the bag he’d set against the gunnel earlier, and turned to his deputy.

“The Dolphin is yours, Mr. Skilling.”

Skilling’s lips fought each other. His eyes were wet. Skilling was a tough man. Schank was touched.

“It’s been an honor, Jeff,” Skilling said. “Your absence will be a burden.”

“Don’t overstay your welcome, Andy.” He put a hand on Skilling’s shoulder. “There are better ships. And, the Lord and Lady know, better captains.”

“Heaven keep you,” the man said.

“Hell forgive you,” Schank said, an old pirate saying.

Skilling laughed and slapped the old quartermaster on the upper arm. Schank slapped the new quartermaster, twice gently on the face, shouldered his bag, and turned to walk down the gang.

For the first time in his adult life, Jefford Schank was without employ. A ghost himself, without a living purpose.

∞

The grand dining room of Angel Shore was three bays wide, as the sitting room. Black silk drapes were tied back to show the moonlit lawn in front of the house, with the cedar-lined, gravel road leading down to the docks. The walls were mustard-papered, the floor the same polished pine that seemed to extend throughout the first floor, the fireplace painted black with gold Coromello trim. The table was well-furnished, silverware and mustard cloth and porcelain decorated in fine, green leaves in a faux Coromello fashion.

The governor sat at the head of the table, decked out in black and mustard formal wear. His wig was as white as his daughter’s skin. Lady Snow sat at the opposite end of the table, her mother having passed several winters before.

Grigarius was not present.

Instead, the rest of the chairs around the table were filled with lords and officials of the Royal Colony of Johannia. Sheriff Sevy of Kingsport. Parson Booth of Binton Parish, coterminous with Binton County where Kingsport and Lord Bernes’s lands lay. The bewigged Lords Amundson and Humway, of the governor’s subordinate households respectively at Bounty Fields and Buck Point, and their wives. There was one empty chair, across the table from Blake, who was the only lord not wearing a powdered wig.

The footmen entered the room with silver trays of food.

“My headman Gamba is absent,” the governor said, nodding to the empty chair. “We expect a shipment tonight at Kingsport. He is there.”

Gamba was not a Vincentian or Strancian name. Blake guessed that the man was a black servant. A prominent one, almost certainly a freed man, if he had a seat at the governor’s table. That was an intriguing deviation from colonial form.

Blake smiled up at a footman reaching over his shoulder to place a tray of boiled potatoes on the table.

“At Kingsport?” Blake asked. “Wouldn’t they rather deliver your goods directly to your own wharf?”

That was apparently the right question. The men around the table sat stiffly in their seats, the women reacting with curiosity. Blake brushed his unwigged hair casually over his shoulder.

“The captain of the Dolphin,” Snow said, attempting to defuse the tension, “is known for a preference to tie up at Kingsport. He pushes his crew, and this often means threading the falls.”

“Captain Durban,” said Sheriff Sevy, “has a reputation for reckless discipline. But I expect the governor’s munitions will be delivered tonight or early in the next week.”

“Gamba will be there to meet him,” the governor said, “in any case.”

“Captain Durban is a godless man,” the parson grumbled, leaning in his chair to allow a footman to place a pie on the table. “Ten years of visiting our colony and he has yet to make a gift to the parish.”

“Archibald,” muttered Lady Amundson. “He gave the church at Raven Forge a baptismal font taken from the monastery at Windows.”

The parson shook his head, staring at his plate. Lord Amundson glared at his wife.

“Parson Booth,” said Snow, “I shall make a gift in Durban’s stead.”

The parson smiled and nodded at her. The governor was frowning, but also nodding at his daughter.

“Munitions?” Blake said as the footmen withdrew, wanting to draw the conversation back to his probable mission.

“Prayers first,” said the parson, glowering at him.

“Of course.” Blake bowed his head, suppressing a smirk.

Parson Booth entreated the group to thank the Lord and Lady for the food before them, and for the good fortune they had enjoyed thus far, and to beseech the Almighty to continue placing a hedge around their efforts, and to promise to keep true to the faith and do their utmost to uphold it against all enemies of the Handrican Church, meaning the Orthodox Coromellos who obsess over the Lady and the Metzals who obsess over the Lord.

Blake took particular interest in the polemics against the Coromellos, whose style Willam Bernes emulated in his house. This was perhaps a gap between the governor and the parson he could shove a wedge into.

“Amen,” said the parson.

“Amen,” echoed the assembly, including the footmen who had retreated to the periphery.

“Let us eat,” said the governor with a forced smile.

The footmen stepped forward to spoon and fork portions onto plates. Soon, all plates were crowded, all glasses were filled with wine or water, and the footmen retreated again to the far walls, those along the outside wall careful not to block the view through the windows.

“Mr. Blake had a question about munitions,” Lord Humway said, his wine held in anticipation before his lips.

The governor spooned potatoes into his mouth. “He did.”

Julius smiled. “It’s Lord Blake, now.”

The room stiffened at the assertion of his recent lordship.

“And, I was curious about the munitions. Are they for a mission to the Bressian Reach?”

Lord Amundson cleared his throat. “That’s hardly dinner table talk.”

Humway sipped at his wine. “It is not. But, Lord Blake has been rather unfortunate in his breeding.”

Lady Snow slapped her silverware against the table.

“Lord Humway!”

Lady Humway glared at her husband with a withering face.

Julius Blake extended an empty hand over the table, fingers separated.

“No, Lord Humway’s words are true. And a truth cannot be an offense.”

He squinted mischievously at Lady Snow. “However unbeseeming its delivery.”

The table stiffened again. The upstart lord had challenged Humway’s propriety. Blake scooped up his fork and speared a square of potato.

“But, tell me, Lord Humway. Who is the most esteemed member of any dynasty?”

Humway huffed dismissively. “I would be intrigued to hear your opinion on that.”

Blake let the potato hover before his face. “But, I was intrigued first. Etiquette would require a response?” His eyes surveyed the table about the propriety of that.

Lord Humway glanced at his wife, a young and dark-haired beauty who was avoiding meeting anyone’s gaze. Humway rolled his eyes and shrugged.

“In my case, that would be,” the governor’s subordinate lord considered it, “Hugh Humway, the man who founded my line at the Battle of the Weevils. He won his lordship for his valor.”

Blake lifted his glass of wine at that. “To Lord Hugh!”

The table felt compelled to meet his toast.

“And your family, Lord Amundson?” Blake swirled the red wine over his plate.

The man blew air through his lips and scanned the faces around the table with a scoffing eye.

“I feel compelled to honor the progenitor of my line, Cass Amundson, who won a lordship for his bravery at Cathedral Siege.”

Lady Amundson put a dainty hand on her husband’s shoulder and leaned in to kiss his cheek. He smiled warmly at that.

Blake ventured a glance at Lady Snow. She was studying him with the intensity he had originally seen when Grigarius barely bested him at Saints War.

“To Lord Cass, as well?” she said.

Blake lifted his glass and the table met the toast. The governor leveled his eyes on Julius over his wine and lifted a chunk of beef to his mouth.

“Lord Bernes,” Blake said. “For your esteemed family?”

Willam Bernes chewed the meat in his mouth and swallowed it.

“My father, Francis Bernes, who earned his lordship as a knight in the Good Foot raids against Strancian rebels.” He nodded over his shoulder at the painting above the mantle, a likeness of Lord Francis in chain mail with a red-and-black Strancian plaid draped over his shoulders in victory.

Blake grinned. “To Lord Francis!” There was an obedient huzzah from the others in attendance, even the footmen, who were fully aware of the family who paid their salaries.

Blake scanned the table, forcing lord and lady alike to meet his gaze.

“We have established that the most esteemed member of a dynasty is the founder of that dynasty.”

He raised his glass and waved it to the assembled diners, then settled his eyes on Lady Snow, whose pale face was intrigued but skeptical.

“In that regard, as a newly anointed lord, am I not the most esteemed member of all of us?”

As Julius Blake downed his wine, the others were silent. He set an emptied glass on the table.

The governor erupted in a storm of laughter. The others hesitantly joined him. Even some of the footmen broke their discipline to laugh with their lord.

“Lord Blake is a master tactician,” the governor roared. “Both in the field and at the table.”

Lady Snow lifted her own glass. Her pink smirk was an enchantment.

“You need to start a dynasty for that to be true.”

Blake nodded at her, his tongue playing against his teeth.

“That I do.”

The governor cleared his throat against the familial innuendo.

“I do have a purpose for you, Lord Blake. And I hope Lord Amundson will forgive my talking business over dinner.”

“My lord,” said Amundson.

“Am I to take command of these munitions?” Blake asked.

“Half of them,” the governor said. He played at his plate, decided to stab a hunk of venison and lift it to his face. “The other half are bound to the south.”

Everyone at the table were suddenly attentive.

“A mission against the Coromello colonies?” the parson asked the governor.

“No.”

“To the Metzal colonies?” asked Lord Humway.

“No,” said Bernes. “To the colonies of the black Emberi. To secure trade in rare hardwoods. Now that many new houses are being built in our colonies, this lumber will be in high demand.”

Blake sat back in his chair. This was an impressive gambit. None of the Vincentian colonies had trade arrangements with the Emberi. The governor was leaning into the future.

Sheriff Sevy shook his head.

“We have enough trees in Johannia, surely.”

“Bah,” the governor said. “Wood that makes up pig-sties is not fit for a fine house.”

He waved a fork at Blake.

“My butler tells me you had a discussion about the construction of our respective houses.”

Blake sat upright.

“We did, my lord.”

“Had I to build Angel Shore again, I’d be buying stone from your quarries rather than baking bricks.”

Blake glanced around the room. Humway and Amundson were beating their eyebrows together. Their own houses were also old structures of brick. Lady Humway grinned admiringly at Lord Blake.

“My point,” said the governor, “is that fashions change and, when things are going well, fashions demand more of us. The Coromellos have Emberi wood and so should we.”

The parson lifted a finger. “Aren’t the Emberi also of the Atzal faith?”

The governor shrugged.

“I suppose they are. Generally speaking. But, they’re not the main Metzals.”

The parson scowled, but Blake nodded at the nuance. “And, the other half of the munitions?”

The governor drew himself erect. He surveyed the faces around the table.

“A mission to the tip of the Ivian Range, to seek entrance to the lands far east.”

There was a collective gasp. Rather than a sortie into the Bressian Reach to secure the existing fur trade, Lord Willam was proposing a push into the unexplored lands beyond the mountains, into the far lands of the magical, inhuman Peyri. There, it was rumored, was an inland sea with untold riches to be exploited. Things undreamt of by the traders and accountants of human colonies.

Lord Humway shook his head.

“But, that mountain pass is in Matthiana colony. Won’t Governor Moore protest?”

Bernes blew air through his lips.

“Elias Moore is too busy peddling cannabis and struggling to manage his fishermen. He’ll invite our sorties into the Ivians as the Marchians invite our raids into the Bressian Reach. Johannian militia, keeping order on the frontiers.”

Snow sat erect in her chair.

“Father, have you discussed this with Elias?”

The governor nodded.

“I’ve sent Moore a letter about our plans to suppress the bull-men and raccoon-men in his territory, who often raid our frontier farms. He has responded with his gratitude.”

“So,” Blake said. He wanted to get back to details. “What will be the make-up of the two parties?”

Governor Bernes lowered his eyes on Blake.

“Mr. Gamba will take the transport to the east. They’re more expendable.”

Snow stiffened at that. Blake noted her reaction and noted that he himself was not in the Ivian party seeking new routes on Peyri frontiers. That was the greater adventure.

He settled an elbow uncouthly on the table. “I’ll be going to engage the Emberi, then.”

The governor nodded. “You and Mr. Grigarius.”

The room went still and silent at the mention of the bear-man’s name. Lady Snow was breathing heavily, her wine glass slowly descending to the table.

“Father.”

The governor cleared his throat. He couldn’t bring himself to look at his daughter.

“I know you want to go with your pet.”

Lord Amundson straightened his wig. Lady Humway poked at her plate.

“I insist, father.”

“Well, then.”

The governor nodded to the footmen, who stepped forward to refill the wine. The distinguished figures seated around the table offered up their glasses. The governor accepted a refill and raised his glass to his daughter.

“In that case, my beloved child, Mr. Gamba and Grigarius will go with you south, instead. Lord Blake will replace Gamba on the mission through the mountains.”

Blake nodded. That was his preferred post. He was more familiar with the inland wilderness than any trade with the Emberi. No one in the Vincentian colonies knew trade with the Emberi.

Lady Snow relaxed, staring at her plate. The governor cocked his head back and forth, as if he’d won a victory he’d long foreseen.

“Being Emberi himself, Gamba may even help that mission navigate their culture.”

Bernes swept his glass back and forth to indicate it was time to end the business conversation and return to dinner. Those seated around the table, including Lord Blake, set forks to food.

“Gamba was a transport trade,” the governor said, offhandedly. “I exchanged him with the Emberi for a smuggler captured at Davis Market.”

Those seated at table glanced back and forth.

“That man,” Bernes said with his eyes on his daughter, “the transport Virginius Ruth, will meet your mission in the Emberi city of Asamar. He now serves the Emberi Lord Rayas of Crossroads plantation there.”

Blake raised his glass with a smirk.

“To Mr. Ruth!”

∞

Schank trudged through the streets of Kingsport looking for an inn that was still open. The street lamps were running out of whale oil and flickering. Of all the colonial ports, he had to get stranded in the tightest run port in the east. There were not even carousers stumbling home late in the mud streets.

Just an old quartermaster with too much gray on his face and not enough of anything on his head, except a black wool cap.

He had a few coins in his bag. Maybe enough for a month in Kingsport. He would’ve been more fortunate had he gone ashore in another colonial port. Kingsport was expensive. Not as expensive as Vincentia, but still more expensive than Margaretsburg or Jacobston. He needed to find a job, and with a swiftness. Kingsport saw richer ships than other ports in the colonies, that was in its favor. But, fewer ships, owing to the falls and the tolls.

Schank sighed and shivered against the cold seeping into his clothes. The mathematics of unemployment was making him tired. He needed to set aside thoughts of his eventual position and focus on the seas in front of him. Or, geographically, behind him. He looked up into the empty sky and saw the stars of the Moth, which the Metzals called Sáramalia, the Hourglass. That confirmed the small hours of the morning for him, at this time of year.

He had his navigational skills to fall back on, if nobody needed a quartermaster.

There were no inn windows lit that he could see. He was in a nice part of town, where businesses closed early and men bedded soon after. He needed to make his way to the rougher parts of the city, where men (and women of commerce) would be keeping the city alive until halfway on the morrow. The streets around him were as silent as a corpse. As silent as a corpse properly should be, at least.

But, there were footsteps, he noticed. He stood in a square, a humble church at one end and a dark-windowed inn at the other. In the center was a tree with pamphlets nailed all around. He listened to the squish of the footsteps until he located their source. Behind him, from the direction of the sea, and the docks. That was not good. He feared the corpse of his old life on the Dolphin was about to break its proper silence.

He turned, hands instinctively resting on his sword and pistol. A team of four men in the port’s livery rounded the darkened inn at a trot and stopped at the site of Schank.

“Are you the quartermaster of the Dolphin?” their sergeant asked. Schank sighed.

“The late quartermaster,” he said, playing at his bottom lip with his tongue. “Mr. Skilling is the current man.”

The sergeant looked back to his men. They nodded at him. The sergeant turned back to Schank.

“You’re the man for it, then. We have an allegation against the captain of the Dolphin, and you are called as a witness.”

Schank felt his open mouth widen into a bitter smile. Allegations against Durban? Only one place from which those could arise. Raf fucking Arland.

“An allegation? From whom?” He knew the answer.

“That’s no matter of yours,” the sergeant growled. “We only need your account of the Dolphin‘s cargo, to compare or contrast against the official ledger.”

Schank settled himself to that. Captain Durban was a slave to profit. Hiding a few crates of munitions for the shadow trade would not be beyond him, although where he might have hidden them or when he might have had them sneaked aboard, Schank could not imagine. Still, he saw an avenue to a petty vengeance against the captain, yet as muddy as the streets of colonial ports. His boots were already muddied.

He smiled at the liveried men.

“And a full accounting I shall give, in service to governor and king.”

The sergeant nodded his men forward.

“Oh, I come willingly. My loyalty to the crown is my shackle. Show me to my quarters.”

The sergeant chuckled.

“You’ll be staying in the transport’s jail.”

Schank nodded, trying to appear solemn at the news. It was better than sleeping in a stinking, muddy alleyway.

∞

“The table is set,” Blake said. He cleared his throat and brushed his hair back. He was determined not to lose again.

Grigarius grinned at his anxiety. Blake appreciated that. An opponent basking in a well-earned victory.

“It is set,” the bear-man said. He nodded Blake to begin as the previous loser. Proper Saints War protocol.

Lady Snow’s smile was warmer than Blake had yet seen. She was also basking in her victory over her father in the matter of Gamba’s mission.

Julius rested his fingers on his Monk piece. He dreaded the distraction, but he had some things he wanted to know.

“Lady Snow,” he said as casually as possible. “Tell me about Mr. Gamba.”

She settled herself in her chair and nodded.

“As father said, he came into our service through an exchange of transports. He comes from the Emberi colony of Antu.”

Julius moved his Monk forward two spaces and nodded at the bear-man.

“What was the charge of his transport?”

Snow glanced at Grigarius, a bit taken aback. The bear-man was intent on the game.

She blushed. “He was charged with smuggling on the Marsh Coast.”

“Well, smuggling requires peculiar insights,” Blake said, watching Grigarius’s paw hovering over his Monk and Inquisitor. He glanced at the lady, who seemed surprised that he had flattered a smuggler. He shrugged at her. “It bodes well for his mission. How has he done here in Johannia?”

Snow sniffed and straightened her dress.

“He’s proven himself quite insightful and trustworthy. We trust him on his own. I’ve urged father to grant him emancipation, but Raymond has an independent streak that father fears.”

“He sits at your father’s table.” Blake stifled a groan as Grigarius moved his Inquisitor against the played Monk.

“He does. He’s our agent in Kingsport, and patrols the roads.”

Blake settled his fingers over his Bishop.

“A sound man. In Kingsport, he’ll be securing the Vincentian transport who is allotted to the eastward mission?”

Snow watched him move the piece to threaten Grigarius’s Inquisitor. The fact of the transport from Handria had not been revealed at the governor’s table. Blake had learned of him through rumor.

“He shall,” she said with lowered lashes. “A man sent here for inciting intrigues, a Mr. Arland.”

Blake sat back in his chair, widening his eyes.

“Intrigues? Sounds a right rogue. Why would the governor put him on such an important task?”

Grigarius shook his furry head. He was focused on the game and trying to ignore the banter. He rubbed his chin, studying the board.

Snow looked into the fireplace.

“He did start trouble between two noble houses in Vincentia. But, as Mr. Gamba’s misdeeds spoke of his insight, Mr. Arland’s misdeeds speak of his.”

She ventured a grin, still looking into the flames.

Grigarius moved his Inquisitor forward, away from the Bishop’s threat.

“As your uncouth behavior at the table speak of yours,” Snow said, lifting her eyes to Blake’s.

He smiled. To have the governor’s daughter endorse one’s “uncouth behavior” was quite a coup.

∞

A black man stood at the door of the jail, casually barring their entrance. Schank knew the only man this would be. Governor Bernes’s man, Raymond Gamba.

Gamba wore leather armor more fit for the frontier than a colonial port. That meant frugality and pragmatism. He didn’t bother with separate outfits for multiple situations. He had three pistols on his belt, a cutlass, and a dagger. That spoke to his readiness for conflict. Schank liked this man.

“Is this the quartermaster?” Gamba said.

“Former,” said Schank, before the sergeant could speak up. “Jefford Schank.”

“Are you ready to witness?”

“I am ready,” said Schank, “to speak the bare truth of what I was let into about the Dolphin‘s cargo.”

Gamba smiled in understanding. He had put “former” and “bare” together in the right calculus. Schank really liked this man.

“I’ll have a good breakfast for you in the morning,” Gamba said with an appreciative look. Apparently, he liked Schank back. Two men in a quiet intrigue against a common foe, Captain Durban.

“Thank you,” Schank said, turning to the guards at his sides. He nodded at the sergeant. “Shall we be seeing me to my quarters?”

Gamba nodded backward toward the jail with an apologetic grin.

“You’ll be sharing a cell, a room, with Mr. Skilling.”

Schank felt his shoulders sink. He chuckled and nodded.

“Andy was also retained as a witness?”

As the men nudged Schank toward the jail with their fists, he shrugged at Gamba.

“I guess you need as many voices as you can get. Captain Durban in here as well?”

“Not yet,” Gamba said, stepping aside. “But, the Dolphin is forbidden from unloading further cargo until we get a full accounting of what’s supposed to be, and what actually is, in her hold.”

“He could run.”

Gamba shook his head. “He’s confined to quarters. If he sets foot ashore, he’ll be shot.”

Schank grinned, nodded, and shuffled into the shadow of the jail. The light of the street’s whale-oil lamps gave way to darkness and stench. The men behind him found it a play to knuckle his back.

“Here it is,” the sergeant said.

He turned and saw Skilling curled up on the floor in the corner of the brick room. At least he was getting a good night’s sleep.

There was a clank of keys as the guard opened the cell. Skilling did not stir. Schank stepped in and the grate was closed behind him. He stood, just breathing, as iron clanked against iron to lock him in. The men exited the jail with exaggerated foot-stomps.

“Mr. Schank,” came a voice from another cell.

Schank groaned. “Mr. Arland.”

“You’ve agreed to be part of my vengeance?”

“I’ve agreed to speak the truth.”

Arland chuckled.

“You know as well as I that Walt Durban kept secrets.”

“We shall see.”

There was a long silence as Schank considered the wisdom of his new situation. He could hear men shuffling to-and-fro on the nearby docks, and the gentle groan of ships’ rigging against the breeze and gentle waves of Kings Cove.

“You,” Arland said, “as well as I, have just cause to see Durban brought to account.”

Schank chose a corner in which to sleep. There was only one reasonable option. He would not sleep near the bars nor too near Mr. Skilling.

“I have cause only to see justice done.”

“And what for you, after the case is decided?”

Schank set his knee against the floor of his cell. He was not eager to let those mathematics back into his thoughts.

“I know not.”

“Perhaps, a grand adventure! Sign yourself to the governor’s cause, whatever he has in mind for me.”

Schank chuckled, laying his head on his forearm.

“You have no idea what that cause might be.”

The quiet lap of gentle waves against the wharf was the only sound for a moment.

“That,” Arland said from his cell, “is the game.”

Schank pulled his knees toward his chest.

“Is it?”

“It is,” said Arland. “You can set your feet ashore in that game, not knowing where it may lead. Would you shirk from setting your feet on a further adventure?”

“Your fancy talk won’t move me, Mr. Arland.”

He wrapped his free arm around his head.

“To keep your eye on me, to keep me from straying from virtue? You nearly scuttled my intrigue between the mates.”

Schank felt his blood grow hot. Two good men died from that intrigue, Durban’s lieutenants. He ran fingers through his failing hair, pushing the wool cap from his head. The stone of the jail floor pressed against his skull.

“I’m not eager for that adventure,” he said. “I don’t have the same loyalty to the governor that I had to the Dolphin.”

There was a long interval of waves lapping against the wharf and sleepy men muttering along the dockside.

“So,” Arland said, “your loyalty is toward seeking a new job. You and I are the same men we ever were. I was duly impressed by your dedication to the Dolphin as you were to my dedication to seek proper retribution for my fate as a transport.”

“Do shut the fuck up.”

“I have provided you temperance in your loyalties, by exposing the captain’s misdeeds. I need your temperance, as you need mine.”

Schank’s teeth ground against each other.

“That’s my confession, Mr. Schank,” Raf said. “I need your temperance.”

“Mr. Arland,” Schank said, “Do shut the fuck up. What we both need in this moment is our sleep.”