CHAPTER THREE

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Grigarius was well on his way to besting Julius Blake at Saints War a second time when Leybold appeared in the doorway.

Grigarius was well on his way to besting Julius Blake at Saints War a second time when Leybold appeared in the doorway.

Snow was grinning when she turned to face her butler. She had been grinning for several minutes at Blake’s expense.

“Yes, Mr. Leybold?”

“Ladies Anna Humway and Irenea Amundson.” He nodded and side-stepped out of the doorway. Blake and Grigarius stood and faced the space he left empty.

Lady Humway, youthful and grim and dark-haired, stepped into the sitting room. She was wearing a dark blue dress trimmed in black fur. Her steel-blue eyes studied the board before rising to greet those sitting around the table. She strode around Blake to take the chair nearest the fireplace, with his assistance.

Lady Amundson stepped into the room next. Her dark hair was coiled in a wild juxtaposition to Anna’s straight, black locks. Her soft brown eyes scanned the room. Blake stepped to retrieve a chair from the wall. He walked around the table and set it between Snow and Anna. Lady Amundson curtseyed, Blake bowed, and the two of them took their seats, followed by the bear-man.

It was Grigarius’s move. This gave Blake time to study the ladies. Snow was staring admirably at Grigarius as he considered his next move. Anna’s eyes were also on the bear-man, contemplatively. Irenea was studying the board.

Her skin was the color of creamed tea. Coupled with her dark coiled hair and eyes, this presented a mystery to Blake. She could be Coromello, most likely Lucaniña, the swarthiest of the Coromellos. But her skin was not olive, more an earthy tone. And her coiled hair spoke of a deeper origin, perhaps a quarteron of Emberi descent.

“As we established at table,” Blake said. The others looked up at him in unison. “Oh, my crude manners. Should we recall the butler to bring refreshments for our new company?”

Snow grinned at him sidelong. “Mr. Leybold?”

The man dutifully stepped into the doorway. Lady Bernes looked to Anna and Irenea.

“Camomile for me,” Lady Humway said.

“I shall share the pot,” Lady Amundson said, “if that’s agreeable.”

Lady Humway smiled and nodded. When eyes returned to the doorway, Mr. Leybold was gone.

“You were saying, Lord Blake?” Lady Amundson was studying him. “What we established at table?”

Had she guessed his curiosity about her ancestry? That would be quite impressive.

“That I came from humble beginnings,” he said.

Irenea’s eyes were inscrutable. Grigarius moved a Layman to block Blake’s Monk.

“Well,” Blake studied the board. “I have heard all about the Bernes, Humway, and Amundson dynasties. I know whence came Mr. Grigarius, who is once again trouncing me on this accursed board.”

He grinned up at the bear-man, who chuckled at him.

“What I do not know is whence you two ladies came. As a newly elevated lord, I have not long been privy to conversations proper to knowing my new peers. I have no insight into your families.”

Anna was distracted by Blake’s hand hovering over the board, but Irenea was nodding at him. She was unmoved to speak first. Try as he might, he could detect neither intrigue nor resentment in her gaze.

“Anna,” she said, “shall you go first?”

Lady Humway sat upright, smiling. “Oh? Yes, of course.”

A pair of footmen appeared, carrying trays. One set a porcelain tea pot, white but decorated in an orange Coromello floral design, near the ladies. The other footman unloaded five matching tea cups. With bows, they exited the sitting room.

“My father was Edmond Parquer, lord in Vincentia. Jerry sought my hand in the homeland and carried me here. And your father?”

Blake smiled, settling his fingers on his remaining Scholar.

“My father was a dockhand, same as me. But in Vincentia. My mother was his legal wife. They had their common honor, but not enough means to attract me to follow in my father’s footsteps. I was taken in by adventurous tales of the new world in the east, so I put my feet on the deck of a ship.”

He moved his Scholar to threaten Grigarius’s Inquisitor.

“The rest we all know. Tragic misadventures on the frontier.”

He frowned off his history in what he hoped was a charming matter. The ladies at table giggled at the maneuver. Grigarius grunted dismissively and scratched at his black-furred face with his claws.

“Do you yet correspond with them? Your parents?” Anna asked, watching the bear-man.

“I do,” Blake said. “And I send them a tithe from Crossing House, to spare my father’s back and my mother’s budget.”

“A worthy son,” she said, not turning her eyes from the contemplative Orsar. “Humble beginnings or no.”

Blake’s eyes rose to meet Irenea’s. She sniffed and straightened her dress.

“Allow me to bring you into the circle of peers, Lord Blake.” She had a suspicious tone.

Julius grabbed the tea pot and began pouring cups full, starting with Lady Amundson.

“I am also,” she shrugged, “somewhat wanting in my history.”

Grigarius’s claws played with the tip of his remaining Inquisitor.

“My father was a successful merchant captain, Mr. Udeas Hammerland. He frequented Kingsport and married a local innskeep, my mother Wanna.”

Blake made a play of studying the board, his eye glancing up to Lady Amundson to keep her talking.

“She was a bit of a legend around Kingsport. Her inn was well-run. The Wild Grapes.”

“That’s still a good inn. I know it.”

“Now run by my brother, Stefal.”

Grigarius played his Inquisitor to take Blake’s Monk.

“Well done, Grig,” Snow said. He nodded at her.

Blake sighed and nodded at the bear-man. He ventured a glance at Lady Amundson.

“Your brother has done well with your mother’s legacy.”

“My mother’s legacy.” A flash of emotion too swift to read.

“A further anecdote?” he said, one hand hovering over his Archbishop. Snow and Anna were focused on the board, or focused on avoiding Irenea’s tale.

“As is the talk in Johannia,” she said, “which you should hear sooner or later, my mother was the product of liaison between a prosperous blacksmith and a freed woman. An Emberi transport.”

Blake elected to move his Archbishop into the bear-man’s strategy. Another loss to Grigarius, but willing.

“Then,” he said, “your rise is more impressive than mine.”

She smirked at that, and Blake lifted a cup of tea to her.

∞

“State your name for the record.”

The captain brushed a hand through his hair. He glanced at the black bicorn hat resting before him on the defendant’s podium. His lips were tight.

“I am Captain Waltier Durban of the Dolphin, out of Channal, Vincentia.”

The magistrate turned to the gentlemen standing in the jury bay.

“Let it be known before these assizes that the accused has named himself as recorded in the log of the proceedings.”

The clerk nodded in the dust hovering in the morning sun.

“You are,” the magistrate turned to the captain, “charged with carrying contraband for the shadow trade beyond your official accounts.”

The captain spat on the floor.

“I steadfastly deny such charges!”

The bailiff took a step forward, hands on the pistols at his belt. The magistrate was unmoved. He turned toward the men standing nearby behind the bar.

“The crown’s first witness. State your name.”

“Mr. Rafelan Arland,” he said, showing his teeth in a wide smile. He brushed his blond curls back in a parody of Captain Durban. “Also out of Channal, Vincentia.”

He turned to the captain with a wink.

“We have much in common, Walt.”

The captain growled.

“That’s quite enough,” said the magistrate. “Will you state for the record the account you heard from the crew of the Dolphin in regard to her cargo.”

Arland cleared his throat, with a sidelong glance at Schank and Skilling.

“Members of the crew let me to know that there was cargo hidden among the ballast, munitions for sale to backwoodsmen who might harbor—”

“Do not stray too far into hearsay, Mr. Arland,” the magistrate warned.

“Quite right,” Raf said. “Their treasonous, republican leanings are not something to which I can speak directly.”

Schank stifled a grin at that. Arland was playing the grand jury like a master.

The courtroom was wood all around. Hardwood floors without a shred of carpet, dark panels along the walls, and surprisingly crude boards across the ceiling. Surprising in that it was not the custom for Kingsport, which enjoyed architectural luxuries the other colonial ports lacked. The judge sat behind a simple, wooden stand. The jurors sat behind a simple, wooden barrier.

“Crown’s second witness. State your name.”

Schank scowled at Raf, who frowned sheepishly.

“Mr. Jefford Schank. Former quartermaster of the Dolphin.”

“And, Mr. Schank. What was your understanding of the said ship’s cargo of munitions?”

“I understood the cargo to consist of thirty-eight crates of long guns, twenty crates of lead and the tools to make them shot, thirteen tuns of powder, and seven crates of horns.”

“That’s a remarkably detailed accounting.” The magistrate turned to the clerk, who nodded without looking up from his scribbling.

“I like to know the ship I’m mastering.”

“Crown’s third witness. State your name.”

Skilling sniffed. “Mr. Handric Skilling, called Andy.”

“That’s fine, Mr. Skilling,” the magistrate said. “You are the current quartermaster of the Dolphin?”

“I am, lately. And the deputy throughout this voyage.”

“Very well. Will you give the jury an accounting of your understanding of the Dolphin‘s cargo?”

“That I will.” Skilling glanced at Schank.

The magistrate sighed. “And, first, you have not conversed with Mr. Schank on this matter since being detained?”

Skilling swallowed and stared at the floor. “I have not.”

“Then, proceed.”

“My understanding was that our ship, the Dolphin, carried thirty-eight crates of long guns, twenty crates of lead and tools, thirteen tuns of gunpowder, and seven crates of powder horns.”

The magistrate nodded. “Thank you, Mr. Skilling.” He turned, first to the jury, and then to the men gathered behind the bar.

“Will the sergeant of the watch step forward?”

A man in port livery stepped through the gate of the bar. He looked tired. Schank presumed the man had been up all night as he, Skilling, and Arland slept in the transports’ jail.

“State your name.”

“Sergeant Roderic Albernon, Kingsport watch.”

“And you oversaw the survey of the Dolphin‘s cargo?”

“In the late morning,” he said with a tilt to his jaw. “Well past my watch.”

The magistrate nodded and grinned at the jury.

“Your diligence is duly appreciated. Will you first state the official accounting given by the papers delivered to the port authority?”

“Aye.” He glanced at Schank and Skilling. “It was precisely as reported by the quartermaster and his deputy.”

The magistrate turned to the recorder. The recorder nodded without looking up from his scribbling. The jurors’ eyes were fixed on Durban, who was breathing hard and staring at the wood floor.

“And,” said the magistrate, “will you give us a full accounting?”

The sergeant shook his head. “In the ship’s hold there were thirty-eight crates of long guns, twenty crates of lead and tools to work it, thirteen tun barrels of powder, and seven crates of horns.”

Durban cleared his throat.

“Then,” the sergeant said, “among the ballast we discovered ten crates of long guns buried under river stones.”

Schank’s eyes settled on the captain. Durban was showing his teeth.

“Eight crates of lead.”

Raf Arland was grinning at the jury.

“Five tun barrels of powder.”

Mr. Skilling’s eyes were wide on Schank.

“And three crates of horns. All sealed by whale skin against the bilge.”

The magistrate nodded solemnly and turned to face the jury.

“This is the evidence upon which we are required by the crown to remand the accused for trial.”

The gentlemen sitting in the jury bay whispered among themselves for a moment, tucking powdered wigs behind their ears. A man finally stood among them. He huffed for a moment as if under great duress to breathe. His eyes squinted at Durban. His lips ground wetly against each other. With an audible flutter of mucus, he cleared his throat.

“I believe,” he surveyed the sitting men to his right and left, “that I state the consensus of the assembled that Captain Durban should indeed be held for trial.”

None of the jurors objected. The judge lifted his gavel.

“The crown witnesses shall give full testimony for the record, at which point they should be delivered unto their liberty or transport. The accused shall be detained for trial.”

He pounded the gavel. Durban slapped his chest with a fist, then turned to glare at Schank.

“No words,” the magistrate warned, then nodded the bailiff toward the captain. The sergeant caught the eye of the magistrate, who nodded. He moved toward the witnesses, waving his palms underhand toward the door.

Schank smiled at Skilling as they turned to walk toward the exit. Andy grinned and nodded with drooped eyes.

“Hope you don’t mind, Jeff, if I join you in seeking new employment. Durban is done.”

Schank laughed. He wasn’t optimistic about his chances.

“I have a prospect,” came a voice behind them.

Both men turned, scowling, at Rafelan Arland. He brushed the blonde curls from his face and smiled wide. The sergeant shoved his back. Beyond him, the bailiff was putting shackles on the wrists of a seething Captain Durban.

Raf grinned. “The sergeant thinks we should talk outside.”

Schank turned and stepped through the door into the street. “We should not talk. Outside or otherwise.”

The morning sun was mottled by cloud. The streets were thronging with merchants, sailors, tradesmen, and Lord and Lady knew who else, going about their day’s business in the dried mud. Skilling stepped up to Schank’s shoulder. Unfortunately, Arland stepped up to the other shoulder.

The captain was led by the bailiff, joined by two liveried soldiers who had been standing outside the door, down the street. He cast a murderous glance over his shoulder, first at Schank, and then at Arland.

“Are we free to go, then?” asked Arland.

“Not quite,” the sergeant said. “You’ll need to come with me to the transport’s jail, where you’ll give a full account for the record. Then you will be remanded to the custody of Mr. Gamba and his platoon.”

Arland nodded at Schank and Skilling. “And these two fine fellows?”

The sergeant slapped hands on the shoulders of the two former quartermasters.

“After their testimony, they’ll be free to go their way.”

Schank lowered his eyes at Raf Arland.

“And go we shall.”

∞

The governor and his underling lords were absent from breakfast. Mr. Leybold had informed Blake that Lord Bernes was on the way to inspect his wharf near the South Falls, and the Amundsons and Humways were well on their way back to their respective plantations. When Blake had asked about the manner of their departure, the butler had mentioned stiffly that Lord Bernes was in good spirits, that the Humways were discussing Yule plans, and the Amundsons were amicable.

Amicable. That, Blake interpreted, was a cover story for a less-than-amicable air between the man and his wife. Perhaps owing to her absence after the lord had gone to bed.

As Leybold passed through the door he paused. Without turning, he said: “The parson and the sheriff also left early.”

He turned to look at Lord Blake over his shoulder.

“Their departure was less remarkable, as they were not here with wives.”

Blake nodded quietly as the man turned and left. As a new lord, and never having served in the house of a lord, he often had to remind himself that servants know the goings-on of their house.

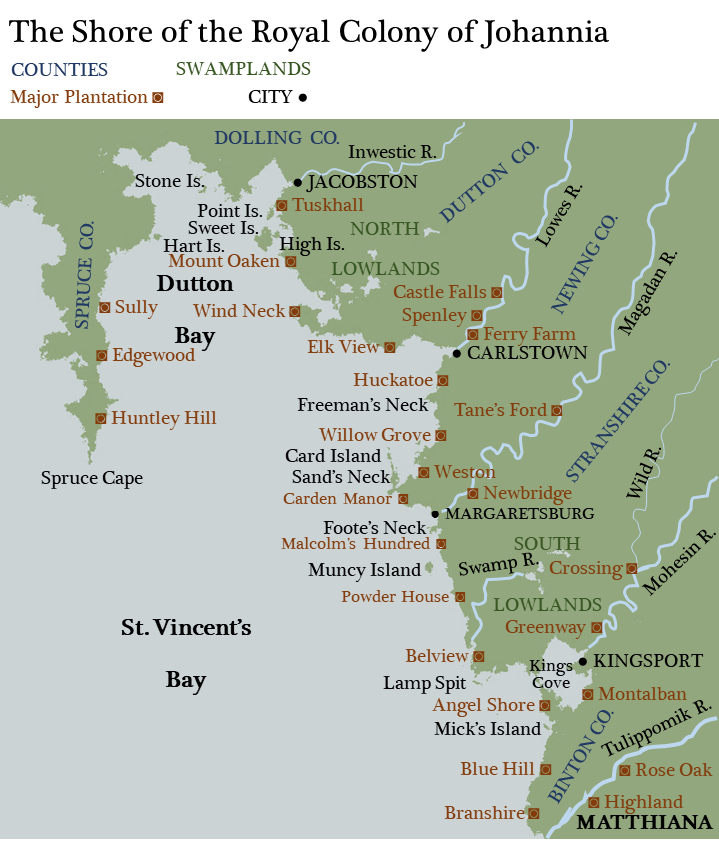

Blake sat in his winter uniform, enjoying the crackle of the fireplace. The morning outside the sitting room window—still visible through the doorway from the dining room—was a vision, the green of cedars and the twin blues of sea and sky. There were sails already gathered to the northwest, perhaps waiting for the tide to thread the falls into Kings Cove. A few sails were headed southwest, toward the canal. Blake noted they were larger, likely full-rigged ships, better able to suffer the governor’s tolls. There were no ships headed toward the governor’s wharf.

Blake took a gentle pleasure from that.

Soon, Mr. Leybold announced the arrival of Lady Snow and Grigarius. They took their seats around the mustard table cloth. Snow straightened her cobalt blue dress as she descended into the chair Grig held for her. The bear-man simply scraped his chair back-and-forth as he sat.

“The table is set,” Blake said to Grigarius, sweeping a hand over the plates and silverware.

Grigarius grinned.

“I’ll try not to outdo you a third time.”

Blake and Snow both laughed, and the lady slapped her napkin into her lap.

“Please,” Blake said. “Do fill your belly as you need.”

The footmen entered with impressive quiet, setting plates of eggs and potatoes and bacon and toast and butter and jelly upon the table. Goblets were filled with milk, water, and apple juice.

“A prayer?” Blake ventured.

“The parson is gone,” said Snow. “But we can pray a moment in silence.”

Which they did, heads bowed.

Julius glanced up. The others met his eyes. With a grin, he set into the food with a hunger.

“I can’t help but wonder, Mr. Grigarius.”

The bear-man barely acknowledged Lord Blake as he filled his plate.

“Are you Lord Bernes’ only mongrel ward?” With a practiced sheepishness, he looked up into the bear-man’s eyes, which were dark and inscrutable. “I apologize for the term, mongrel, if it is offensive.”

Grig glanced at Lady Snow, who was busy filling her plate.

“Mongrel is an accurate term. Its offense is not mine to negotiate. There is no better term as a substitute.”

“The giants and the Peyri created your kind,” Blake said. “Mixing their own blood with wild animals. I often think that the words we use are not entirely fair.”

Grigarius nodded, with an over-medium egg speared by his fork. He moved it to his plate, careful not to break the yolk.

“I think,” Blake said, “that bear-giant would better describe you.”

“I would prefer Orsar,” Grigarius grunted.

“That is fair,” Blake said. He lifted potatoes into his mouth.

Lady Snow grinned purposefully over the table. Her eyes settled on Blake’s.

“The jelly is apricot, from this year’s harvest.” She pronounce it with an “ay” rather than an “ah.” Quite posh.

“I do like apricot,” said Grigarius, matching her accent.

“As do I,” echoed Blake. He pointed at the Orsar with his fork. “So, you act as Lord Bernes’ liaison to the allied Orsar now?”

Grigarius scraped butter onto a slice of toast.

“Not always.” He settled the knife on his plate and gathered up the jelly bowl with a glare at Blake. “There was a bear-man causing trouble in Sweep Valley once. Known as the Weird One. He had a partner, a natural bear, a male. Known as the Hell Lord.”

Blake sat up straight.

“A partner?”

Grigarius nodded and cleaned his teeth with his tongue.

“An unholy union, according to the Church. The Weird One could speak, wore clothes. The Hell Lord was a beast. He could not speak. He was but an animal.”

Blake set to breaking up his egg. He nodded a footman forward to apply pepper.

“And, they were both male,” Blake noted, digging into his bacon.

“Yes,” Grigarius said. “I slew them for Lord Bernes. They could not be brought into contract.”

Snow sniffed, spreading apricot jelly on her toast.

“So,” Blake said, “no other wards from among the … um …”

“From among us mongrels?” Grigarius said.

“Yes.” Blake frowned at the bear-man’s surrender to the term.

The Orsar scooped potatoes into his maul.

“Lord Bernes tried to domesticate a bull-man, a bull-giant, named Hernan once.”

Snow sighed. “Hernan was not indicative of—” She lost her words.

Grig nodded.

“Hernan was a problem. His aggression was too strong. He raped the lord’s cows and opposed the governor at every turn until he had to be put down.”

Julius took a few breaths, knife hovering over his toast.

“Put down?”

Grigarius swallowed and scowled at Lord Blake.

“He was put down by Lord Amundson’s militia as he attempted to cross the bridge at the Locks.”

Snow stared at her plate, playing at an ivory pendant at her breast. She looked particularly resolved about an issue that had not been spoken.

“Well,” Blake said. He wanted to be judicious in his words. “That seems to grant some privilege to the Orsar over the Tauri.”

Grigarius nodded.

“Indeed.”

“I know from personal experience,” Blake said, “of the intractability of the Tauri.”

“Indeed,” Grigarius repeated. He set into his plate with renewed hunger. “You put down the Black Horn.”

“I did. But, let’s move on to more polite matters,” said Blake. “Lady Snow, that is an attractive ivory pendant.”

She lifted her fingers from it, surprised by his attention. Julius could see it was a circle with a curled design inside.

“It’s a gift,” she said, blushing. “From an adventurer in the south.”

“Mr. Gamba?” he asked. “Or another.”

She stiffened and lifted a piece of toast.

“Mr. Gamba, indeed. It has a special significance in Emberi culture.”

Blake nodded and tried to focus on breakfast.

“A token of the life that he left behind.”

“Indeed.”

∞

The joyous morning filled Kingsport with a raucous trade in fine goods from the west and rougher goods from the colony. Cloth, buttons, and gold loaded down. Wood, tobacco, and furs loaded up. Everyone was bright with cheer. Even the sky shone bliss upon the land.

Schank and Skilling were not so happy. They had secured several prospects, to be sure, as regular members of the crews of middling vessels. Working their way back up to quartermaster. Considering the manner in which they’d both lost that position recently, that rise would be fiercely opposed by any captain under whose banner they sailed.

At the very least, Schank comforted himself, Durban would be having a worse day. Probably hoping a fool’s hope that his crude republican allies in the backwoods might brave Kingsport to free him from jail. With one of every ten bodies in the street wearing the king’s livery in one capacity or another, that seemed unwise.

Skilling cleared his throat. Schank turned to him. A red-haired water boy nodded and passed between them, carrying skins over both shoulders.

“There’s always Mr. Arland’s offer.”

Schank scoffed and started walking again.

“He’s in no position to be offering.”

“Not exactly, no.”

An old lady gestured to her cart of squash and carrots. Schank waved her off.

“But, he was a specified transport. The governor requested him by name once word of his sentence reached Johannia.”

“He’s still just an indenture.”

“Aye, but one with some purpose.”

Schank rubbed his cheek with the palm of his hand. There was something in it, he had to admit. Rarely did the governor of a colony specify a transport by name. Only Arland’s reputation for intrigue could have inspired that request. Bernes had seen a sign he had not. Skilling had seen a sign he had not. He swallowed his pride and confessed to himself that there must be some opportunity in it.

“Here we are,” said Mr. Skilling. He stopped and Schank stopped.

As luck would have it, they were standing outside the transports’ jail. Schank pulled the wool cap from his skull and ran his fingers over his failing hair.

The denizens of Kingsport made their merry way around them, carrying sacks and crates and armfuls of goods. Schank pulled the cap back over his head and sent a scowl Skilling’s way.

He stepped forward and knocked on the door.

“Mr. Gamba!”

He looked back at Skillling, who simply grinned and shrugged his shoulders.

Schank felt himself resigned, his own shoulders sinking. He struggled to raise his fist to the door, and knocked again.

“Mr. Gamba!”

There was a clank of keys. The door swung inward. There stood Mr. Gamba, in his leather armor.

“Mr. Schank.”

He took a deep breath.

“Mr. Skilling and I recommend ourselves to your cause.”

Gamba’s brows lowered.

“You do? In what capacity?”

“We know your transport through—” he glanced at Skilling. “Difficult circumstances. We understand his powers at intrigue, and have learned to negotiate our way ’round them.”

“By delivering your captain into captivity.”

Schank drew erect at that.

“Walt Durban set his own snare.”

Gamba nodded and frowned, considering that.

“Given your reputation as the governor’s headman,” Schank said, “I suspect we won’t face such a dilemma of loyalties.”

The man took a deep breath and studied the former quartermaster’s face.

“You want to help me deliver him to Angel Shore.”

“We do,” Schank said. “And, then to submit ourselves to the governor’s purposes.”

Gamba grinned, but warmly.

“So, they’re not hiring quartermasters along the wharf.”

Skilling cleared his throat. Schank felt his lips crushed against each other.

“They are not.” He endeavored to match the headman’s grin.

Gamba nodded.

“You did well in court. I respect that. It put you in a bad way, yet you spoke the truth nonetheless.”

Schank nodded.

“We did. We could do no other.”

“I would hope you honor that legacy as we bring Mr. Arland into the governor’s service.”