CHAPTER FOUR

“Move out!” Gamba shouted.

“Move out!” Gamba shouted.

Jefford Schank was impressed at the men the governor’s agent commanded. There were a dozen of them, and they looked a rough lot. The transports were in a wagon topped by an iron cage. Raf Arland sat among three Emberi indenture trades, and they did not seem happy with his pale-faced company. He looked too much like their captors, Schank suspected.

He wondered how they felt about Mr. Gamba’s dark face leading a team of white men carrying them into servitude.

The driver snapped his crop and the horses clomped into motion. Gamba waved his men forward by shoving his long gun through the air.

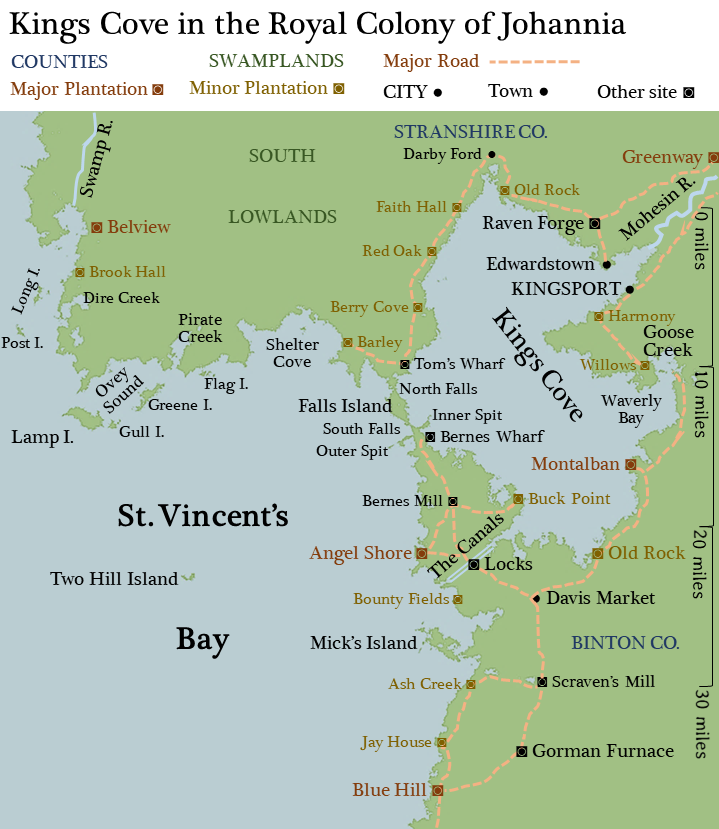

Schank shrugged at Skilling and started walking, a hand on his pistol. The merry folk thronging the afternoon streets of Kingsport barely noticed them as they clanged and clambered east through the city.

They were in sight of the city’s log palisade when they heard the gunfire.

Gamba raised his long gun. “Halt!”

He looked back toward the wharves, as did everyone.

Schank ventured a glance at Skilling. They both swallowed. Another volley sounded in the distance.

Gamba showed Schank his teeth.

“I would guess that’s your captain’s friends,” he growled.

Schank nodded.

“Not our captain, now. Not our problem, now.”

He glanced at Arland and immediately regretted it. The man was grinning wildly at him.

“Through the gate!” Gamba roared.

The good people along the street were jogging toward the gunfire. Their curiosity had overcome their fear.

The team moved forward, horses clomping, cage and shackles clanking.

Raf chuckled. “Durban and his partisans are going to be problem when we move inland,” he said.

Schank refused to look at him.

“He won’t get out of Kingsport,” Skilling said. Schank was grateful the man spoke instead of him.

Arland laughed at it. “You didn’t think that I would get you on this team.”

“Shut it!” Schank barked. Gamba glared back at him.

The team passed through Kingsport’s southeast gate to the sound of Arland’s chuckling. His fellow captives were looking at him and grinning, perhaps not understanding the exchange but encouraged by the wedge Raf had against their captors.

∞

Snow and Grigarius walked down Angel Shore’s wharf road as the sun descended through the bright autumn afternoon. St. Vincent’s Bay was a play of colors, blue and green and white. Sails swarmed north toward the falls and south toward the governor’s canal. The perpetual calculus of colonial profit. Snow saw them as men betting against her father’s tolls, or against death in the swirling waters of the South Falls. How much were the lives of a captain’s crew worth, in gold? The canal’s tolls straddled that figure, according the sails glowing in St. Vincent’s Bay.

Spreading her black and burgundy dress with pinched fingers, she turned casually toward the cedars lining the empty gravel road. Grigarius followed her.

She caressed the trunk of a cedar like the back of a favored pet. She reached her other hand to Grigarius’ face and scratched his fur.

“Talk with me about the board.”

“The board?”

She sighed and stepped outside the cedars, into the carefully managed grass. Grigarius followed her. She stared out over the bay.

“The board we’re all on.”

The bear-man stood near her shoulder. “Your father’s plans are perilous. You understand our mission to the south is a feint.”

“Is it?”

“He claims to seek access to rare woods in the Emberi colonies. But, beyond the colony of Ohuru is another pass into the Peyrian Sea.”

She felt her shoulders tighten. “You think our mission is the same as the transport’s?”

“We both venture toward the east. His path is a winter’s path through a mountain pass. Your father knows the peril in that path. He’s playing a double-feint.”

Snow trusted the bear-man’s sense of the game. He had rarely been bested at Saints War or any other game, and never by her father. His incursions into the backwoods were always a success. And, she knew this was a hard indictment for Grig to make. Her father had saved his life. Given him a new life. He would not accuse him of deceit lightly.

“Who among us would carry my father’s true aim?”

Grigarius did not hesitate. “Mr. Gamba. Blake’s mission is a sacrifice.”

Snow felt water in her eyes. She also trusted Gamba, had trusted him for years, throughout her childhood. To think he had kept such a secret from her, that her father had. She felt her childhood falling from her like autumn leaves. Unlike the cedars behind them, she could not remain green. She must grow into her name.

She felt Grigarius’s crude paw on her shoulder.

“My apologies,” he grumbled. “I only read the board as I see it.”

She smiled at him with wet eyes. “I know.”

He removed his paw and glanced over his shoulder, toward the house, beyond it toward the backwoods of the colony.

“If you gave Blake the other pendant, you could better know the progress of both missions.”

She shook her head. Her finger rose to her throat, where the ivory Emberi pendant rested against her pale Handrian skin. Blake was too much like her father, just wanting to establish a noble dynasty. He did not seem a romantic or ethical man. Not someone she’d want to speak with across a distance with the magic of the twin pendants she had been given by Gamba.

“I know Lord Blake’s mission will succeed.”

Grigarius shook, his leather armor squeaking. He rarely did that.

“You do?”

“Most likely,” she hedged. “He knows the winters of the highlands. If he can patrol Relles Pass in winter, he can manage the Vale of Ladjor. The mission with doubts in my head, and my heart, is ours.”

He put his paw on her shoulder again. She smiled and lifted her fingers to play in his fur. She had grown up with this bear-man, had been delighted with his antics as a cub and impressed with his growing prowess as a warrior and a master of any board he set his mind to.

Grig growled thoughtfully.

“I see Gamba’s play, and he’s not a man who loses.”

She chuckled and looked up into the Orsar’s deep brown eyes.

“He was transported.”

Grigarius grinned.

“Into a better life. He won that game, too, in his way. As did I. As did this man Arland from Vincentia who will be going with Blake into the Vale of Ladjor.”

He nodded, thinking through the plays. “Yes. Both missions will reach the Peyrian Sea.”

Snow nodded.

“And, my lady, I’ll keep an eye on Gamba for you.”

She stiffened. “I don’t mistrust Gamba to keep me safe.”

“Even so.”

She stepped forward out of the Orsar’s touch. The wind off the bay was cool, threatening winter. She’d miss Yule at Angel Shore for the first time in her life. She’d be in a country that didn’t celebrate Yule, a Metzal land. But, there would be no need to “bring in the green” because the lands south were green throughout the year.

Snow glanced back and Grigarius and smiled.

“It will be quite a thing to see the Peyrian Sea,” she said. “And the Peyri themselves. The memoirs of Archer and Moreton describe them as the most beautiful creatures in the world.”

“I would like to meet one of their lion mongrels.”

She laughed.

“You want to test your mettle?”

He growled and shook his furry head.

“No. Maybe. But, I would just like to measure the man.”

Snow played at her teeth with her tongue.

“Or to measure the woman?”

That earned a deep, grumbling laugh.

“We’ll see who we meet.”

∞

Gamba’s team passed Harmony plantation before the afternoon had died, Harmony house’s black bricks revealed under a fading whitewash. With lazy nods at the soldiers of the house, the team turned south across the King’s Peninsula at a forced march. Gamba insisted on letting the horses set the pace. Schank was simultaneously impressed an annoyed. He was too old for this rigor.

As the glittering waters of Kings Cove disappeared beyond the grand house of Harmony behind them, the road passed through fields laid bare by harvest, and patches of gourds just then coming to fruit. Pompkins and squash and autumn cucumbers were temptations Schank felt in his stomach. A good pie, a soup, or even a salad. Crows perched atop nearby posts staring at the gourds as if puzzled at how to make good use of them.

“Do you think he made it out?” Raf said. He was rubbing the blond scruff on his chin with thumb and forefinger. Schank knew it was a practiced gesture.

“I honestly don’t care,” he said, “but no, I do not estimate a bunch of filthy hillbillies escaped the most well-guarded city in the colonies with a captain accused of betraying the crown.”

Skilling nudged him with an elbow in solidarity.

“Well,” Raf said thoughtfully, “we should care. Backwoods rebels must have good intelligence to survive. They’ll surely ferret out where we’re going.”

The other transports were enjoying the banter. Schank wasn’t sure they could even understand the Handrian tongue. They simply knew that Raf was getting Schank’s goat.

“You do my caring for me,” Schank grunted. “And, you’re talking past the sale. I’ve known enough crooked merchants to recognize that tactic. I don’t think those backwoods rebels are going to survive to make use of any intelligence they might have.”

Raf grinned and descended into his thoughts. Which was where Schank preferred him to remain.

For a long while, the road passed through dead fields, the fruits of life stripped from them. Graveyards of grain. No, Schank knew. Those dead fields were not graveyards. The fruits of the life cut down there had been hauled away to loaves and cakes. Only the ghosts of those fields remained, haunting the dried furrows, and the stalks that had been cut short by the scythe.

“Will we make the Goose Creek ferry?” one of the armed men asked Gamba.

The headman shrugged. “If we keep our pace. Are you growing weary?”

“No sir. No sir!”

Schank was impressed by the loyalty. Gamba demanded respect and obedience.

The man regathered himself and strode closer to the headman. Schank noted the other men listening intently.

“It’s just, sir… Willows has finer food than the waystation on the other side.”

Gamba looked back at the man, not skipping a step. He nodded.

“We’ll camp on the near shore,” he said.

The man glanced around at the others, who were smiling at his initiative.

“If,” Gamba said, turning forward. “If we reach Willows before nightfall.”

The man nodded his head, but the headman did not see it. His gaze was fixed ahead, where the road entered the dark green forest of the peninsula’s high ground, beyond the end of the dead fields.

“If we do not make that pace,” Gamba said loudly, “we will cross Goose Creek Cove even if it takes us past midnight.”

∞

“The Vale of Ladjor,” Bernes said, lifting a brandy snifter to his mouth. He did not finish his thought. Blake knew that meant that he should finish it himself.

“The threats to our mission? I count them as three.”

Willam Bernes sipped his brandy and set the glass down beside a new deck of cards. The dark and empty bay glittered in the moonlight through the window, over the governor’s shoulder. The various gambles of ships’ captains had been settled.

They were alone in the sitting room. Other than Mr. Leybold standing dutifully just outside the door.

“Only three?” the governor said.

“Lord Bernes.” Blake shook his head. “You selected me to lead this mission to the east. How many tests must I pass?”

The man’s sallow face grinned. He scraped the white wig from his head and set it on the back of the chair to his left. He was answering Blake with a show of informality. Even so, his natural hair was as white as the wig.

“Not a test. Just an assessment.”

Blake frowned and nodded.

“Fair enough. Yes, three threats.”

He scooped up the deck and flipped through the cards. Finding the Jack of Clubs, he slapped it on the table, face-up.

“First, the weather.”

It was Lord Bernes’ turn to frown and nod.

“Winter in Johannia is rough enough,” Blake said, “but I imagine that it’s far worse in the Vale. Hedged in by the mountains of the Tinesian and Cantian ranges. There will be no stocked woodsman’s cabins, which we rely on quite heavily in our incursions up Sweep River and into Relles Pass. After supplies run out, we’ll be living off the land. A land we don’t know.”

Bernes shrugged.

“All land has game. And Ladjor is not as far north as the Pass.”

Blake nodded. Those were rough truths. He shuffled through the deck. He found the King of Spades and slapped it on the table.

“That brings me to the second threat. The wolf-men of Ladjor, whom the Peyri created to guard their lands from the giants’ mongrels. They were bred to keep the giants’ Orsar and Tauri out of the east during those ancient wars.”

The governor lifted his snifter.

“The wolf-men, yes. And the Peyris’ Anzi and Raton mongrels?”

Blake scoffed, lifting his own brandy. “The goat-men have long ago gone rogue. They’re friendly with the Tauri. And the raccoon-men? They’re too roguish by nature to concern themselves about anything but raiding farms. The wolf-men are loyal. They are the only real Peyri mongrel threat.”

Bernes nodded and sipped at his brandy. Blake joined him. It was good brandy. Most likely imported from the homeland.

“You have a third card?”

Blake set his glass on the table, grinning. He shuffled until he found the Queen of Diamonds. He laid it softly on the table beside the other two cards.

“Rival interests.”

The glass in the governor’s hand shook, then descended slowly to rest on the table. Blake had dug until he found the doubts in Bernes’ mind.

“You think someone might seek to sabotage the mission to keep me from making contact with the Peyri.”

Blake tilted his head sideways.

“I think an opportunity this lucrative would attract all sorts of intrigue.”

“The governor of Matthiana knows of my aims. I’ve offered him a share in its profits.”

Blake nodded. “Lord Moore’s confidants might not share his opinion on the matter.”

Bernes took that in. Blake slid the face-up cards together and shuffled them back into the deck.

“There might also be rumors in your own colony. Opponents of your governorship, or of the crown itself, who would want to see us fail.”

Bernes lifted icy blue eyes to Blake.

“You suspect there could be a republican partisan in your party?”

“That.” He set the deck back on the table. “Or that some such might organize a party to follow and oppose us.”

The governor gathered his wig and set it on his lap.

“Mr. Leybold, you are dismissed.”

Quiet footsteps retreated into the house.

The governor groaned himself standing and wagged a finger at Blake.

“You are the man for it.”

Blake leaned back in his chair, and felt his muscles release from a tension he had not recognized during the discussion.

The governor shuffled toward the door of the sitting room. Blake guessed that this had not been his first glass of brandy that evening.

Blake scraped his chair backward and turned, still sitting, toward Bernes. He considered standing, but kept his seat. He might be Bernes’ man, but he was still a lord. A peer. The old man paused at the door in his journey upstairs.

“Governor,” Blake said, “I will see this done. Triple-threat or no.”

Bernes nodded without turning and shook his wig back at the man.

“Kill whom you need. The assigned men. The transport. Whomever you deem is desert of killing.”

Blake sat up straight as the governor made his way out of the room, leaving the new lord to consider his way ahead with only the crackle of the fireplace to converse with him. The night outside the windows had become a silent black.

∞

A man strode into the camp as Gamba’s men lit fires and made good the provisions they’d been granted by the lord of Willows.

The team had made Waverly Bay before nightfall and won Gamba’s wager. Even Raf Arland, who had taken not a step from when he climbed into the transport’s cart, had loudly expressed his awe at the progress. Schank, whose complaining legs were accustomed to the limited perimeters of a sailing ship, was doubly impressed.

The man calmly invading the camp was wearing a parson’s frock. His passage incited the men to stand and take notice. Schank sat on a tree stump near the ferry wharf, watching as the man walked a straight line toward the transports’ cart.

The man’s boots beat a steady rhythm on the packed earth. The gentle waves of Goose Creek inlet lapped against the mud shore in a contrary rhythm. A family of ducks stood at the edge of the firelight, considering the men in the camp.

Taking note of the approaching parson, the black men in the cart paused in eating their salted pork to nudge Raf Arland. The man looked up and, upon seeing the parson’s eyes on him, handed his meat to his fellows.

The man stopped at the corner of the cart.

“I am Archibald Booth, parson of Binton parish, coterminous with the County of Binton.”

Raf wiped his mouth with a dirty, cotton sleeve.

“Rafelan Arland, recently out of Channal.”

He extended a hand through the bars. The parson shook his head with a grimace, reticent to touch the transport.

“You think yourself assigned to a glorious endeavor in the interest of the crown’s colony.”

Raf withdrew his hand and set elbows on knees.

“I would prefer that to any imaginable alternative.”

The parson lowered his eyes.

“You are to enter a realm of rebellion, of heresy, of paganism. Of necromancy.”

Raf shook his shoulders at that.

“Necromancy?”

Booth nodded solemnly.

“The backwoods are the realm of death. Evil spirits haunt its hollows and groves.”

“Well then,” Arland ventured a glance at Schank. There was something in the transport’s eyes that impressed and concerned the old sailor. A twinkle of intrigue.

“Good man,” Arland said. “I shall have to keep my faith in the Lord and the Lady to protect me from these evil spirits.”

There was not the merest hint of perceptible mockery in his tone. Schank let go his concern and nudged Skilling, sitting on a rude wooden stool, to pay attention to the exchange.

“That is a good and pious plan,” the parson said, glowing with encouragement. “Do you have scripture?”

“I do not,” Raf said. His eyes were vulnerable and solicitous. “My own was relieved of me in Vincentia when I was transported. Could you secure me a copy to study?”

The parson smiled warmly and dug into his frock. His pale hand produced a book. He held it out.

The black men in the cart were glancing back and forth, among each other and at Arland. Raf nodded at them with a practiced air of seriousness, and reached his hand through the bars.

Schank noted a caress of fingers as the book was exchanged. Raf’s eyes were locked on the parson’s. He was playing some secret gambit, Schank knew. The parson withdrew his hand with a notable discomfort. The man was shaken.

“You m-may be,” the parson stuttered. He gathered his thoughts. Raf leaned in, tucking the scripture slowly into his shirt.

The parson sniffed and drew himself erect.

“You may be enlightened to know that the governor is good enough to transport in exchange all of our colony’s deviants to the Emberi colonies to the south.”

Raf nodded contritely.

“That would be the proper handling of such matters. I have heard that our headman was such an exchange.”

Schank stole a look at Gamba, who was sitting with his men on a crude bench, drinking from a bottle and eating pork. When he looked back at the parson, the man was also looking at the headman.

“Indeed. It is an illustrative anecdote.” The parson was choosing his words carefully.

“The man traded for him?” Raf said.

The parson looked up at him.

“He was caught smuggling in Davis Market. But he had other charges. Charges suppressed.”

“Deviancy,” Raf said, lowering his head. As if in shame.

The parson stepped forward.

“Your intrigues between houses in Vincentia. Did they have anything to do with the ladies of those houses?”

Raf looked up, eyes wide.

“Are you looking to take my confession?”

“I am only looking to save you from deviancy, if you wish to be saved.”

The transport gave Schank a look. A mischief played in his eyebrows before he turned back to the parson.

“I do wish to be saved from the fate of this smuggler. What were his suppressed charges?”

Schank sat upright. Skilling drew himself straight beside him. Arland was seeking insight into Gamba’s transport exchange, into the history of the man who was then his master. Perhaps something to use against him. Schank was suddenly impressed at Arland’s talent at intrigue.

The parson straightened his frock.

“The man was taken with women’s fashions. He procured them, in his smuggling misdeeds, for the ladies of this colony.”

Raf nodded. “He was unduly acquainted with the habits of women.”

The parson again straightened his frock. “Indeed. And for that he was transported to the hands of a foreign power.”

“Thank you, parson.” Arland patted the scripture against his breast. “I shall seek redemption for all of my sins. Thank you from my soul.”

The parson bowed, turned, and made his way out of the camp.

Schank looked at Skilling, whose countenance was agape. He took that in, stood, and stepped toward the transport’s cart as the parson vanished into the night.

“You,” he said, pointing. “Mr. Arland, you may be the best bullshitter I have ever encountered.”

The black men in the cage looked to Raf for his reaction. The man grinned and patted his shirt.

“We both have a little faith to recover.”

∞

The team moved by barges across Goose Creek inlet in the cold and foggy morning, passing low grassy islands in the mist, flocks of ducks dipping into the waters for their breakfast, and a skiff of the lord’s fishermen gathering the day’s dinner. The inlet was so shallow, the crude ferry barges were poled along by Willows men in absurdly yellow livery, along a path marked by red buoys.

The former quartermasters were on the barge carrying the prison cart, so they could keep an eye on Raf, according to Gamba. After all, that was what they were there for. Raf took that to heart with a double-tap of the scripture under his shirt.

With the fog close on all sides, he was tempted to pull the book out and start reading. To ward off necromantic influences. The low-lying islands of the inlet would be a perfect place to hide bodies. Some rake who had seduced a fisherman’s wife. A whore threatening to blackmail the lord of Waverly. An inconveniently illegitimate baby.

Arland was sure there were ghosts hiding in the mists and grasses. He looked ahead, trying to catch site of the far dock. He could barely make out the barge ahead in the morning fog.

“This is fucking creepy,” he said to nobody in particular.

The Emberi transports looked at him with eyes that told him they were having similar thoughts. He suddenly felt guilty. They almost certainly thought he was the local among them. His attitude was affecting theirs. He grinned and waved at them. They nodded and smiled.

“Are you worried the other transports won’t be with you,” Schank said, “when you pull whatever shit you got planned?”

He chuckled and the other transports laughed with him.

“You,” he said, “are doing a great job keeping me in line.”

Schank rolled his eyes and glared at Skilling. For his part, Skilling shrugged.

“No,” Raf said. “I was getting spooked and it was spooking the others. I caught it, you caught it.”

Schank stared into the passing water shaking his head.

“Don’t, Arland.”

Raf felt the weight of scripture on his chest. “No, seriously.”

Schank slowly raised his eyes. His face shook, his eyes tightened.

“I was messing with the parson,” he said, “but his talk about evil spirits messed with me.”

Schank rolled his eyes again.

“Arland, there are no ghosts. I’ve known hundreds of men who died and not one of them have I seen since.”

Raf leaned back. He looked at the other transports and nodded.

“If you say so.”

He glanced ahead. Gamba’s barge was tying up at a dock, men in yellow livery wrapping lines around posts.

They had made the waystation. The crossing was done.

Gamba and his men disembarked as Raf’s barge pulled up on the opposite side of the dock. When the transport cart rumbled onto shore, Raf caught the crude wooden buildings of the waystation in the fading fog. Gamba’s men were certainly right in their assessment of the relative accommodations. He was glad for the dinner he’d had the night before, on the other side.

The mud road beyond the waystation threaded a verge between firs and a rocky shoreline as the morning mist burned off in the rising sun. The firs gave way to dead fields as they approached Montalban plantation. To the west, the waters stretched off to the horizon, first the calm waves of Waverly Bay then the choppy surf of Kings Cove proper, spangled with sails. Dark birds speckled the growing blue of the sky as the sun broke through a layer of mottled cloud.

Raf was quiet as they passed Montalban and Old Rock plantations along the shore, fine houses of black brick with summer whitewash fading down the seams. As the road moved inland for a second time, fields gave way again to tall stands of evergreens to either side.

As the afternoon grew late, Raf felt the mischievous urge to play at Schank’s loyalties, but those loyalties seemed too clear in his mind to merit further annoyance. The old quartermaster and his deputy Skilling needed gainful employment. They were with him out of necessity. And, necessity was a tight knot.

No, Raymond Gamba was his man. A black Emberi, having risen to a position of great trust under a Vincentian lord. That spoke of potential intrigue.

That man would lead his mission into the east. He needed inside that man’s mind. He knew precious little about him, only that he was a foreign transport, traded for a man who was captured at a place called Davis Market.

Raf wrapped his hands around the bars of his moving prison. His eyes were on the old quartermaster, marching ahead of the transport cart.

“Mr. Schank,” he said, his mind wrapped in the intrigue.

The old quartermaster rubbed his black wool cap with a hand. He was clearly not amenable to conversation.

Raf ventured: “The road to Angel Shore has taken us past several plantations.”

“Yes,” the man said, without turning. “It has.”

“Are there no towns on the road? No mills or furnaces. No markets?”

Schank cracked his neck and gave Skilling an annoyed frown before lifting his eyes to Arland over his shoulder.

“Davis Market, which I’m sure you’ve heard of, is right around the next bend.”

Raf smiled. What a providence!

“Thank you, Mr. Schank.”

The man groaned and marched forward.

“Are you thirsty, fellows?” Raf turned to the other inmates and lifted his hand to his mouth in a drinking gesture. They nodded enthusiastically.

He smiled and leaned into the bars.

“Mr. Gamba, may we have some water? The transports have indicated to me that they are parched.”

The headman stopped in his tracks with a nod for his men to march on. He gave Schank a nasty glare as the man marched past him. The old quartermaster shrugged with a sheepish grin. Gamba snatched a large waterskin from his belt and awaited the cart. As it came alongside him, he began walking again and lifted the skin.

Arland took the waterskin and handed it to the nearest transport. The man took it eagerly.

“We are nearing the place where your exchange was arrested.”

Gamba nodded and looked into Raf’s eyes. His hands were on his sword and pistol.

“We are. Davis Market. Mr. Virginius Ruth was caught there selling smuggled goods.”

Raf sniffed and sat upright.

“Cloth goods, I gather. That’s a good trade. Were you a smuggler?”

He grimaced as Gamba’s eyes fell away.

“In your former life, I mean. I understand you have made an honest career here in Johannia.”

Gamba flashed suspicion at him. He struggled to appear contrite.

“As I wish to,” Raf said. “I do not want to remain in indenture.”

Gamba cleared his throat.

“I was a bandit in the south. I killed, I stole, I sold. Smuggling was among my charges.”

Raf rubbed his chin.

“I never had the head for smuggling. The economics of it eludes me.”

The headman shook his head. He looked into the cart to assess the progress of his waterskin. The second black prisoner was lifting it to his mouth.

“I was compelled to—” Raf sighed and shook his head. Then, looked to Gamba for his reaction. The man was implacable.

“I was compelled to seek my ambition by inciting intrigues among powerful men. It went badly, as you can see.”

Gamba grinned.

“I can see a lot about you.” He lowered his face at the transport. “Much of it may not make you happy.”

Raf nodded. The last Emberi prisoner handed the waterskin to him. He took a short swig and handed it back through the bars. Gamba took it and set to reattaching it to his belt.

“Much of it does not make me happy. But, I see the folly in it now.”

Gamba chuckled, his hands at work at his waist. “Do you?”

“We are assigned to the west, for a more honest intrigue. A new trade?”

The headman’s eyes sprayed suspicion at him. Raf raised his palms.

“I seek out information. It’s my gift.”

“Your curse, perhaps,” the man said.

Raf nodded.

“But, my gifts are at your command now. If I deploy them in this new mission to the governor’s benefit, my hope is that I might follow in your admirable footsteps.”

Gamba stared at the mud of the road before him, grinning and shaking his head. Raf noted Schank and Skilling, marching alongside the team pulling the cart, glancing back at their conversation.

“You are a gifted man,” Gamba said. He shoved his belt in place. “If you truly wish to follow in my footsteps ahead, stop obsessing over my footsteps behind.”

Raf sat upright. He nodded in acknowledgement of a well-played phrase.

“That I will, Mr. Gamba. Trust that I will.”

The headman cleared his throat and stepped toward the front of the column with heavy stomps of boots in mud.