This is the fourth installment of my Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about certain roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found repeated in many stories. They synchronize stories with the narrative instincts of the human mind, and imbue them with a distinct psychological presence.

This is the fourth installment of my Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about certain roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found repeated in many stories. They synchronize stories with the narrative instincts of the human mind, and imbue them with a distinct psychological presence.

You don’t have to be a dyed-in-the-wool Jungian to recognize that archetypes are a core element in storytelling. You don’t even have to like the term “archetype.” Call them what you want: tropes, memes, patterns, threads, modes, models, Platonic forms, şurôt, whatever.

But, no matter what you call them or why they exist, they do exist, and they have undeniable storytelling power.

Before moving on to the subtler aspects of archetypal storytelling, I want to get through what I consider the Big Four character types. So far, we’ve looked at the Hero and the Rough. Today’s installment is the Guru.

_

THE GURU

The Guru is a mysterious figure, typically much older than the Hero, who shows up to bring the Hero into the adventure that will transform him or to provide a key gift (often a piece of advice) that enables the Hero to succeed in his quest.

The Guru is a mysterious figure, typically much older than the Hero, who shows up to bring the Hero into the adventure that will transform him or to provide a key gift (often a piece of advice) that enables the Hero to succeed in his quest.

Occasionally, you’ll see this character referred to as the Mentor. I elected not to use this term because it has been tainted a bit (quite a bit) by pop business culture. The Guru is much more than a professional adviser, and the Hero’s career advancement is often the furthest thing from her mind.

Yes, her. There’s some disagreement about whether the word Guru can be used to refer to women (Gurvani is one suggested alternative) but I prefer to consider the word fully adopted from Sanskrit into English as a gender neutral term. For example, I also choose not to use Heroine for female Heroes. Just assume I mean both genders. Or neither: a Guru could also be a neuter character (like a robot) or even an abstract value that informs the Hero’s quest.

In fact, leaning toward the abstract is a characteristic the Guru has in common with the Villain. As we’ll develop further in the Villains installment, the Guru and the Villain are often in the same elder generation, and both can serve, embody, or even simply be abstract values. Think about how Kenobi and Vader embody and serve different sides of the Force which are themselves simply stand-ins for the familiar Good and Evil.

Significantly, the Guru is often bearded to indicate his seniority. That is, unless the Guru is a woman, like the Spider Woman invoked in the Ray Roberts painting I used for the Guru icon. Whether a sage or a crone, the Guru is the carrier of wisdom. The Guru grounds the Hero in this wisdom, closing off foolish paths that might seem reasonable, but he also opens the Hero’s mind to unseen possibilities that this wisdom encompasses.

GURU VS. ROUGH

The Guru’s facial hair trope brings us to the Rough, who is also often surrounded by furry imagery. Think Han Solo with his inseparable sidekick Chewbacca, or scruffy-faced Aragorn, or the furry beast-man Enkidu of Mesopotamian legend. The Rough is also usually older than the Hero, although not quite as old as the Guru. This means both Guru and Rough represent greater experience relative to the Hero.

Thus, we need to get into how to tell these two archetypes apart.

In the Rough’s installment, we discussed how the Guru’s serene wisdom contrasts with the Rough’s cynical street-wise nature. If you’re interested in that dynamic, there’s a lot more info there … so I won’t repeat it here except to remind the reader of the key to understanding who is the Rough and who is the Guru in any story you’re reading or watching:

In many stories, there’s a Philosophical Banter plot point, where the pragmatic swagger of the Rough butts heads with the superstitious caution of the Guru. In Star Wars, it’s the classic “ancient weapons and hokey religions” scene aboard the Millennium Falcon, where Solo expounds on the superiority of having a blaster by your side. In The Lord of the Rings, this plot archetype is expressed during the Council of Elrond, with Gandalf’s rebuke of Boromir’s proposal to use the Ring against the Enemy.

(Yes, I know I identified Aragorn as the Rough earlier; you’ll have to read the previous installment to see how this Rough doubling between Aragorn and Boromir plays out.)

Note that the banter is often about the Power of the story, a character-like archetype that represents the driving force in the story’s underlying theme. In Star Wars, it’s the Force. In The Lord of the Rings, it’s the Ring itself.

In the Western True Grit (both Portis’s novel and the Coen Bros film adaptation) the Power is the “true grit” for which Maddy chooses US Marshall Rooster Cogburn to hunt down the man who killed her father. In the Philosophical Banter scene, Rooster and Texas Ranger LaBoeuf trade insults about trail-hardiness, with LaBoeuf taking the practical angle and Cogburn playing it more superstitiously. I won’t spoil the scene: read the book or watch the film. When the Philosophical Banter starts, you’ll see how the two veteran trail hands play out the Guru-Rough antagonism in perfect form.

There’s another interesting way the Guru and Rough parallel each other in different lanes. Among screenwriters, there’s a maxim that “the mentor dies on page 75,” which is right after the midpoint of the story. This is where Gandalf falls into the depths of Khazad-dûm while fighting the Balrog, and where Kenobi is felled by Vader in the Death Star. In both cases, the Guru comes back, either as a disembodied voice or as Gandalf the White.

Sometimes in fact, the Guru only pretends to die, as Betty White’s character does in Ryan Reynolds and Sandra Bullock’s romcom, The Proposal.

Paralleling the Guru Dies (and Comes Back) plot cycle is a Goodbye-Hello cycle, wherein the Rough abandons or betrays the Hero only to return/redeem himself later. Think about Han Solo leaving after packing up his reward for rescuing Princess Leia, only to zoom back in to save Luke during the final battle. Or think of Boromir trying to seize the Ring from Frodo, only to redeem himself by dying to save Merry and Pippin.

Both of these Hokey-Pokey plot points send characters on a boomerang trajectory, but they nevertheless carry very different archetypal energies. The Guru’s death is often a martyrdom of sorts, dying in virtue, while the Rough’s abandonment is a selfish move, leaving for vice. It serves to show that, while the Rough might have more experience than the Hero, he’s still got a long way to go.

The Guru is the one who’s really most on top of things.

_

KEY ELEMENTS OF GURU SEMANTIC FIELD

To sum up (and before moving on to a specific case study of a Guru) let’s list the key elements of Guru semantic field.

- The Guru usually brings the Hero into the adventure. (Think Gandalf and Bilbo/Frodo, or Kenobi and Skywalker.)

- The Guru is distinguished from the Rough in a Philosophical Banter scene.

- The Guru knows the Power, explains it, and has mastered it. (Otherwise, how could he be the Guru?)

- The Guru has an opposite take on the Power from the Villain, which represents the moral conflict facing the Hero.

- The Guru is older than the Hero (and the Rough), and often of the same generation as the Villain.

- The Guru “dies on page 75.” This is a virtuous death, usually fighting the Villain.

- The spirit of the Guru lives on in some fashion.

Now that we have our elements, we can do some archetypal chemistry…

_

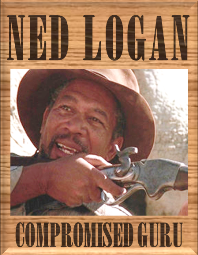

THE COMPROMISED GURU

For our case study, let’s discuss an unusual Guru, so you don’t get the idea that they’re all perfect, Kenobi/Gandalf types. For example, the Guru role can be overturned by the thematic intent of the storyteller, so that many of his Guru characteristics are reversed, often by mirroring the Rough. After all, archetypes are really semantic fields rather than discrete roles, and swapping archetypal elements back and forth can have dramatic literary effect. When a Guru character’s Guru energy gets displaced like this, either by absorbing functions from another archetype or surrendering his own Guru functions to another character, we end up with a “compromised” Guru.

For our case study, let’s discuss an unusual Guru, so you don’t get the idea that they’re all perfect, Kenobi/Gandalf types. For example, the Guru role can be overturned by the thematic intent of the storyteller, so that many of his Guru characteristics are reversed, often by mirroring the Rough. After all, archetypes are really semantic fields rather than discrete roles, and swapping archetypal elements back and forth can have dramatic literary effect. When a Guru character’s Guru energy gets displaced like this, either by absorbing functions from another archetype or surrendering his own Guru functions to another character, we end up with a “compromised” Guru.

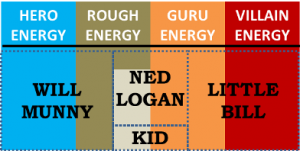

In Clint Eastwood’s masterpiece Unforgiven, the aging gunfighter Will Munny is just about the roughest and unlikeliest Hero imaginable. He’s nearing the end of his life, almost smothered by experience, and is only able to carry the Hero role’s necessary naïveté because he’s been reformed to moral innocence by his late wife and is now trying to raise pigs for a living—and failing at it from inexperience.

So, since the Hero is absorbing a lot of Rough energy, the Rough in the story becomes an ironic anti-Rough: the Schofield Kid, whose tough and world-wise braggadocio is backed up by nothing. This archetypal vacuum leads to further displacement of energy in a domino effect: typically, it’s the Guru who brings the green Hero into the adventure, but in Unforgiven it’s the anti-Rough Kid who shows up to tempt veteran gunfighter Will with a bounty for killing two cowboys.

And why not have the fake Rough do this in a story where the adventure is a terrible, terrible idea? No real Guru would do such a thing!

Which brings us to our compromised Guru, Ned Logan. In many ways, Ned helps Will absorb some of the Rough energy displaced from the blustering anti-Rough Kid. For example, Ned tries to tempt Will with drink and whores. Not very Guru-like. He also timidly goes along with Will’s repeated insistence that he “ain’t like that no more,” abdicating his Guru duty to remind the Hero of his suppressed potential in an exchange that foreshadows the film’s climax.

MUNNY: I ain’t like that no more … I ain’t the same, Ned. Claudia, she straightened me up, cleared me of drinking whiskey and all. Just cause we’re going on this killing, that don’t mean I’m going to go back to being the way I was … You remember that drover I shot through the mouth and his teeth came out the back of his head?

NED: Yeah…

MUNNY: I think about him now and again. He didn’t do anything to deserve getting shot, at least nothing I could remember when I sobered up.

NED: Well, you ain’t like that no more.

MUNNY: That’s right. I’m just a fella now. I ain’t no different than anyone else no more.

So why am I pegging Ned as a compromised Guru instead of just the Rough? Couldn’t the Kid be more of an upside-down Guru than an upside-down Rough, since his unexpected appearance over Will’s pig sty is so very much like Gandalf showing up in the Shire to drag Bilbo off on a quest?

For one thing, when Will rides off to drag his old partner into the misadventure, Ned at first rejects the lure of profit (not very Rough-like) and tells Will, “We ain’t bad men no more; shit, we’re farmers!” Sounds like a wise position to me.

Even better, pay close attention to the Philosophical Banter scene … which, as in many stories, takes place during a calm pause, early in the journey. In Unforgiven, it’s at a campsite. When the Kid asks Ned how many men he has killed, Ned’s simple response is “What the hell’s that to you?” The Kid’s faux practical answer is that he needs to know what kind of fellows he’s riding with. Ned then turns the question on the Kid, who resorts to obvious bullshit.

Ned’s Guru wisdom here is about the awful, Zen-like simplicity of violence: you don’t talk about it, you don’t think about it, you just do it. Or you don’t. Later, when Ned “dies on page 75” it’s a moral death, his inability to embody the awful Power of mindless violence. Echoing his original objection that they “ain’t bad men no more,” Ned discovers that he’s not the killer he used to be when he simply can’t bring himself to pull the trigger on the first cowboy they ambush.

However, Ned’s first, moral death is merely another Rough energy absorption and reversal. Whereas a genuine Rough would have run off at this point for profit’s sake, Ned leaves because he can’t bring himself to profit from killing. It’s only having burned off this last bit of Rough energy—displaced (from the Kid) and reversed—that Ned is able to ride off on his own to be captured and suffer his Guru martyrdom: a final, physical death at the hands of the Villain, sheriff “Little Bill” Daggett, who has no problem committing violence.

Further confirmation of Ned’s Guru status (if we need it) is that he presages the Dig Deep Down moment that carries the Hero throughout the climax.

At the beginning of the Philosophical Banter scene, the Kid questions Will about a rumor that he single-handedly killed two deputies who had their rifles on him at point-blank range. Will, having been ostensibly reformed of such behavior by his late wife, claims he doesn’t remember. This also serves to introduce the idea Ned then confirms: violence is something you just do, not chatter about. However, later during a rainstorm, the Guru takes the Hero aside:

NED: You know, when he was talking back there about the time them deputies had the drop on you and Pete?

MUNNY: Yeah.

NED: Well, I remember it was three men you shot, Will, not two.

MUNNY: Well I ain’t like that no more, Ned…

Ned, like any good Guru, sees more in Will than he’s able to see in himself, and he finds another way of getting at the truth about the Hero’s potential:

NED: Still think it’s going to be easy to kill them cowboys?

MUNNY: If we don’t drown first.

This simple assertion reverses Munny’s earlier denials, and it foreshadows the moment when compromised Ned has to hand his rifle over so Munny can finish off the first cowboy. Moreover, by bringing this truth out of Munny, the Ned also foreshadows the Hero’s final victory, when he Digs Deep Down and brings the story’s Power to bear. And, just as Kenobi’s disembodied spirit returns to remind Luke of the Force just before he fires the shot that destroys the Death Star, Ned’s soul-less body is waiting for Will outside Skinny’s saloon just before the Hero starts firing the shots that destroy just about everyone inside. Including the Villain.

Which is as good a segue as any to bring the chief bad guy into the Guru discussion.

The Villain, like the Guru, is usually in tune with the story’s Power, but often with a quite different take. Again, the Power in Unforgiven is the awful, Zen-like simplicity of violence. You don’t think about it, you don’t talk about it, you just do it. Note how the Villain lectures a Wild West pulp writer who has made a living writing down the dishonest boasting of violent men like English Bob. During a particularly tense scene in the jailhouse, Little Bill tells the writer: “Being a good shot, being quick with a pistol, that don’t do no harm, but it don’t mean much next to being cool-headed. A man who will keep his head and not get rattled under fire, like as not, he’ll kill you.”

The writer counters, “If the other fella is quicker and fires first—” but Little Bill is adamant: “Then he’ll be hurrying and he’ll miss … It ain’t so easy to shoot a man anyhow, especially if the son-of-a-bitch is shooting back at you. I mean, that’ll just flat rattle some folks.” You can’t think about it. You just kill.

And yes, along with the displacement of the Kid’s Rough energy to the Hero and Guru characters (resulting in a hollow Rough who weeps his Goodbye moment to the Hero without any hope of a return), Unforgiven displaces some of the Guru energy onto the Villain. It’s usually the Guru who explains the Power but, although Ned lets Will know he still has killing in him, it’s Little Bill who is left to provide the audience with an exposition on violence.

And yes, along with the displacement of the Kid’s Rough energy to the Hero and Guru characters (resulting in a hollow Rough who weeps his Goodbye moment to the Hero without any hope of a return), Unforgiven displaces some of the Guru energy onto the Villain. It’s usually the Guru who explains the Power but, although Ned lets Will know he still has killing in him, it’s Little Bill who is left to provide the audience with an exposition on violence.

And, guess when he does it! Immediately after the Philosophical Banter scene where the Guru normally would do so. In fact, as soon as Little Bill provides us a demonstration of how having “a good blaster at your side” isn’t quite enough (by tempting English Bob to take a pistol and shoot his way out of jail), the film immediately goes into the rainstorm scene above where Ned ties off the loose threads from the campsite’s Banter by reminding Will of his own violent potential.

The lesson of Unforgiven is that a good story does not have to cling to a rigid role formula, but a powerful story certainly should engage the full range of archetypal energy, even if it has to shuffle it around or even reverse it. Faced with telling the story of an adventure that never should have happened, Eastwood cannot play the archetypes straight, including the Guru. The Guru can’t bring the Hero to the story, because a genuine Guru wouldn’t. Instead, a profit-seeking fake Rough steps in, and the Hero goes looking for the Guru after the fact. And, although the Guru sees the Hero’s potential like any good Guru would, he can’t play a master-pupil role (like Kenobi does) because the road they’re on is a foolish one.

So, we end up with a compromised Guru, a Guru who knows the Power, has seen it, and knows the Hero has it .. but he is not a master of it himself. When this hole in the Guru’s function shows up, the Villain steps in to fill it.

But, by the time the Hero shows up at the climax, even the Villain has let himself be tempted (by the pulp writer) into talk, boasting, and moralizing about violence. He has lost his mastery over the Power, and is bested by the Hero, both physically and philosophically.

Earlier, when Will was denying his Power, he obsesses about how a drover he killed “didn’t do anything to deserve getting shot.” Now, with Little Bill pinned to the saloon floor and staring up the barrel of Will’s rifle, everything is turned over:

LITTLE BILL: I don’t deserve this. To die like this. I was building a house.

MUNNY: Deserve’s got nothing to do with it.

LITTLE BILL: I’ll see you in hell, William Munny.

MUNNY (cocks rifle): Yeah.

When it comes down to the simple finality of violence, all other, subtler concerns vanish. “What the hell’s that to you?” as Ned asked. Sure, Will might have killed Bill in retaliation for killing Ned (and killed Skinny for decorating the saloon with his friend) but, morally, deserve’s got nothing to do with killing.

You don’t think about it, you don’t talk about it, you don’t moralize. You just do it.

Writing Archetypes – The Proximate and Ultimate Villains | J. Nelson Leith

July 22, 2015 at 7:23 pm

[…] often start their stories in a state of innocence and ignorance. As we’ve seen before, the Guru often has to bring the adventure to her. Something is wrong in the world, the Guru knows, and the […]