It’s time for another installment of the Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about certain roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found repeated in many stories. They synchronize those stories with the narrative instincts of the human mind, and imbue them with a distinct psychological presence.

It’s time for another installment of the Writing Archetypes series, where I talk about certain roles, scenes, and plot points that can be found repeated in many stories. They synchronize those stories with the narrative instincts of the human mind, and imbue them with a distinct psychological presence.

You don’t have to be a dyed-in-the-wool Jungian to recognize that archetypes are a core element in storytelling. You don’t even have to like the term “archetype.” Call them what you like: tropes, memes, patterns, threads, modes, models, Platonic forms, şurôt, whatever.

But, no matter what you call them or why they exist, they do exist, and they have undeniable storytelling power.

During the last few installments we learned a little about Heroes, Companions, Gurus, etc. Today we explore the Villain archetype, which is often divided into Proximate and Ultimate threats. The archetypal “bad guy” seems like a simple role—just oppose the Hero, right?—but there’s a lot of subtlety and complexity lying just under the surface.

WHAT IS A VILLAIN?

We are often encouraged to refer to the character who opposes the lead as the antagonist, since the main character is traditionally called the protagonist. But, these terms referred to work-roles for stage actors in ancient Greece, not so much narrative roles for characters.

The protagonist of a story is the character the audience is intended to identify with; even when flawed, this character is the Hero of the story. Their suffering is a tragedy, their success a victory. The antagonist, by extension, is more than simply antagonistic. The antagonist is indeed a Villain who feeds the tragedy or fails to thwart the success.

If this scheme seems a bit morally simplistic, take heart. In this Writing Archetypes series, the Villain can be a force of nature, perhaps metaphorically a force within the Hero herself. And, Villains can certainly be complex enough that an equally authentic version of the story could be told with them as the Hero.

The fact that we recognize the Villainous nature of the opposing energy in a tale doesn’t mean we have to reduce a human character to a moral cartoon or deny the moral complexity of conflict. It simply means that stories are told from a perspective, and in stories told from perspectives there are Heroes and Villains. We identify with the Hero, and therefore we are meant to see the character opposing him or her as a threat. That is, a Villain.

THE VILLAIN IS THE THEME

Heroes often start their stories in a state of innocence and ignorance. As we’ve seen before, the Guru often has to bring the adventure to her. Something is wrong in the world, the Guru knows, and the Hero is the key to fixing it.

What’s wrong in the world is embodied by the Villain.

The innately polemical nature of the Hero-Villain relationship (or, more accurately, the Guru/Hero-Villain relationship) defines the theme of your story. If you’re writing a story, and it’s strong, readers like it, but you can’t quite identify the theme of the story, just ask yourself: What does my Villain represent?

Chances are, your Villain’s primary motive is some easily identifiable evil. If it’s a political evil like the old mainstays of capitalism, socialism, racism, sexual immorality, etc. try to distill it down to one of the classic sins: Pride, Rage, Lust, Envy, Gluttony, Greed, or Sloth. If you end up with a vague evil, like Destructiveness, try to put a more specific spin on it. Why is the Villain destructive?

Knowing that your Villain is essentially a negative example of your (perhaps unconscious) moral theme will give you better insight into how to put real narrative power into your Villain. And, as a bonus, it will help you write those painful necessities of the published writer, the logline and the summary.

TWO LAYERS OF VILLAINY

Just as the Hero often has heroic helpers—among them the Companion, the Rough, and the Guru—the Villain can also have helper characters. Since the focus of the story is on the Hero, and thus the Hero’s entourage, most of the Villain’s supplemental characters are two-dimensional Minions, like Darth Maul, or one-dimensional Hordes like the Imperial Stormtroopers.

Just as the Hero often has heroic helpers—among them the Companion, the Rough, and the Guru—the Villain can also have helper characters. Since the focus of the story is on the Hero, and thus the Hero’s entourage, most of the Villain’s supplemental characters are two-dimensional Minions, like Darth Maul, or one-dimensional Hordes like the Imperial Stormtroopers.

(And yes, most of the “Minions” of the Despicable Me franchise are, archetype-wise, Hordes rather than Minions. In Minions, the Minion Kevin is in fact the Hero. So, let’s try to keep the archetypal terminology separate from the cartoon franchise.)

But, every once in a while, one or more of the Villainous entourage rise above Horde or Minion status. To distinguish these levels of Villainy, we’ll call the two archetypes the Ultimate Villain and the Proximate Villain.

ULTIMATE VILLAIN

The Ultimate Villain, or UV, is perhaps the easiest to understand. This is the baddest baddy in the tale. Because of this extreme nature and the fact that we’re not intended to identify with Villains, the UV is often reduced to abstraction, occasionally little more than the embodiment of an evil, or of Evil itself, that is the evil of your theme.

The Ultimate Villain, or UV, is perhaps the easiest to understand. This is the baddest baddy in the tale. Because of this extreme nature and the fact that we’re not intended to identify with Villains, the UV is often reduced to abstraction, occasionally little more than the embodiment of an evil, or of Evil itself, that is the evil of your theme.

Think the glowing orange sphere in The Fifth Element, or Tolkien’s Eye of Sauron. Very abstract, indeed.

Because the Villains are the morally contemptible side of the story’s conflict, the UV character can often fall prey to harsh stereotyping, either intended or merely perceived. Take, for example, the Jewish antagonist Shylock in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, a money-lender who plays into a variety of Christian polemics against Jews.

In fact, even when no such malicious demographic characterization is intended, the UV can mistakenly feed—or, be mistakenly perceived as feeding—a slanderous social narrative, particularly when the Villain and Hero fall on opposite sides of some demographic divide like race, sex, or (as in Merchant) religion. This is another reason the Ultimate Villain often gets dehumanized and abstracted. It’s much safer when the Bad Guy isn’t a guy at all, but just a thing or a vague spirit of Badness.

On the other hand, writers with a more political bent can make the Ultimate Villain purposefully demographic. For example, some critics have argued that Shakespeare’s treatment of Shylock is intentionally anti-Semitic. (Other critics, of course, have disagreed.) Even this purposefully political approach to the UV can lean into abstraction, though. One might interpret To Kill a Mockingbird so that the real Ultimate Villain is bigotry, rather than any of the human characters.

The larger point here is that the Ultimate Villain’s role is inherently polemical and points toward (or embodies) some abstract evil. Thus, a writer should take care with the UV, lest some unintended message worm its way into the story. Being aware of the dangers of the UV can save a writer a lot of defensive explaining later on.

PROXIMATE VILLAIN

Perhaps because the UV is so abstract and perhaps because, in terms of the fun of the Hero overcoming obstacles, the more the merrier, stories often have better-developed lesser Villain who may or may not be a servant of the Ultimate Villain. Because this lesser Villain is closer to the Hero in both concreteness and in narrative space, we’ll call him the Proximate Villain or PV.

Perhaps because the UV is so abstract and perhaps because, in terms of the fun of the Hero overcoming obstacles, the more the merrier, stories often have better-developed lesser Villain who may or may not be a servant of the Ultimate Villain. Because this lesser Villain is closer to the Hero in both concreteness and in narrative space, we’ll call him the Proximate Villain or PV.

The PV is the one who confronts the Hero earlier and most often, particularly the more abstract the Ultimate Villain is. For example, in the original Star Wars trilogy, Darth Vader is the PV, with the Emperor as the UV. In Romeo + Juliet (and the play on which it was based) the PV is Tybalt while the UV is the family feud between the Montagues and Capulets. Saruman and Gollum play PV roles in The Lord of the Rings, with Sauron (and his Ring) as their UV.

Because the UV is often such an abstract menace with relatively little human personality, the PV in powerful stories is often a scene-stealer. As we are warned by the advice blog ScriptShadow:

Write your villain to steal the show – I read SO MANY boring villains with no personality. It’s no wonder I forget them the instant I put down the script. Honestly, I can count the number of memorable villains I’ve read in screenplays this year on one hand! To prevent this, write your villain to steal the show.

You need a intriguing PV to keep the narrative alive. This is why The Fifth Element needs Zorg, and why Jurassic Park needed Dennis Nedry. They’re not only easy to hate, they’re fun to watch.

SUBTYPES AND OVERLAPS

The Proximate Villain can overlap with other villainous archetypes. For example, the PV can be conflated with the Turncoat, who initially aligns with the Hero but shifts to the Villain’s entourage later. A pure Turncoat who really carries very little PV energy would be Cypher from The Matrix. A Turncoat who is also a full-fledged Proximate Villain would be Saruman.

There’s the Soft, whose loyalty to the Ultimate Villain is in play. He’s sort of a reverse Turncoat. Darth Vader eventually turns out to be a Soft, but most Softs show their relative compassion earlier on. The Cowboys who defect to Wyatt Earp’s side in Tombstone fall into this category.

Then there’s the Brute, who is typically more cruel and less sophisticated than the Ultimate Villain. The Brute is a sort of anti-Soft. Often the Brute is often little more than a Minion. Think Billy Crash from Django Unchained.

But, keep your mind open about Django. We’ll come back to the subtleties of that film later.

ONE GOES UP, THE OTHER DOWN

Only a Proximate Villain can die before the climax of the story. In fact, there is often a waxing/waning relationship between Proximate and Ultimate Villains, with the PV showing up first and fading in the rising shadow the UV casts over the story as it develops.

Note that the Emperor never even shows up in the original Star Wars trilogy’s first episode (which was Episode IV).

Likewise, the UV of the original Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy—which, if you hadn’t noticed, is Greed—doesn’t get an embodiment (as Lord Cutler Beckett) until the second episode. Barbossa doubles up as Guru and Proximate Villain in Curse of the Black Pearl, but sheds the PV role to Davy Jones in the following episodes.

HAVE FUN WITH YOUR VILLAINS

Considering all of these dynamics between the UV and PV, the relationship between the Hero and the Proximate Villain is a playground for the writer. Sometimes the PV is simply another monster to kill on the way to the UV’s “level boss.” However, the PV can have an antagonistic relationship with the UV, as with Jones and Beckett, or even a sympathetic relationship with the Hero, as with Vader and Luke.

Considering all of these dynamics between the UV and PV, the relationship between the Hero and the Proximate Villain is a playground for the writer. Sometimes the PV is simply another monster to kill on the way to the UV’s “level boss.” However, the PV can have an antagonistic relationship with the UV, as with Jones and Beckett, or even a sympathetic relationship with the Hero, as with Vader and Luke.

This can add layers of complexity to the story. Remember how I said that only a Proximate Villain can die before the climax? Well, think about Tarantino’s Django Unchained. Calvin Candie, the plantation owner, is the Ultimate Villain, right? Wrong. Candie is out of the picture well before the climax.

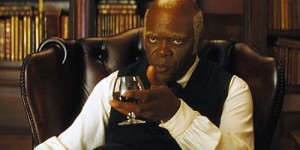

After Candie is killed (by the Guru, not the Hero!) and Django is captured, who is it that sends the Hero off to a mine to be worked to death? And, who is the last Villain to die? Stephen, played by the formidable Samuel L. Jackson, Candie’s chief house slave.

In light of the overall moral theme of that film, which was a polemic against slavery, let it sink in a moment that the Ultimate Villain was himself a slave.